Borosil: Toughened glass

Borosil has weathered many a storm, and by expanding into consumer businesses, is preparing for the big leap ahead

Three generations of the Borosil Glass Works family: BL Kheruka (left), Pradeep Kheruka (centre) and Shreevar Kheruka

Image: Mexy Xavier

Shreevar Kheruka is every bit the CEO who has done his time in the trenches—nimble yet restrained, ambitious yet cautious, mindful of the past, yet quick to embrace the future.

Such traits are possibly must-haves in a man who is steering his half-a-century old family business through a transformation he believes was long overdue. Shreevar, 37, is moulding Borosil into a consumer-focussed firm that does the whole nine yards in kitchenware. With an eye on the future, he is looking beyond glass. Today, Borosil’s consumer portfolio comprises microwave-proof glassware, storage containers, opalware and appliances.

At the heart of the exercise lies Shreevar’s quest to sprint to the ₹1,000-crore annual sales mark, a befitting landmark for a company of Borosil’s vintage, yet one that has remained elusive.

For until fiscal 2017-18, Borosil was short by ₹365 crore.

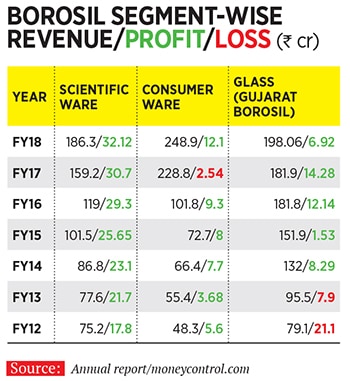

The firm has now started reaping a rich harvest of the revitalised consumer business, which has toppled its legacy industrial glass and scientific products verticals to become the biggest revenue generator, with ₹249 crore in FY18. The scientific products and industrial glass businesses chipped in with ₹186 crore and ₹200 crore respectively. Scientific products, however, was the biggest contributor to the bottomline (see chart).

“Our background was B2B [business-to-business]. Taking advantage of the Borosil brand happened only in the last five years. This should have happened 2000 onwards,” says Shreevar, MD and CEO of the ₹1,900-crore (market capitalisation) Borosil Glass Works.

Borosil had made a feeble attempt at selling bakeware and drinking glasses in the late 1990s, without any notable success. “We were quite conservative, and spent money from whatever we were earning. The consumer turnover of the company was so low that we could never market or advertise to the level we wanted,” says Shreevar.

The old guard agrees. “If we had gotten into marketing of consumer products earlier across the range, it would have been beneficial,” says Pradeep Kheruka, vice chairman and non-executive director at Borosil Glass Works, and Shreevar’s father.

While the realisation had dawned early, the needle didn’t move much until FY11, when, after being in business for about two decades, Borosil Glass Works, breached the ₹100 crore annual sales mark for the first time. (Gujarat Borosil, the industrial glass business, first clocked ₹100 crore revenue in fiscal 2013-14.)

Until then, it was all about putting the house in order.

*****

His days in Boston, however, were numbered. Shreevar had promised Pradeep that he would return to Mumbai immediately after completing a dual degree in science, finance, entrepreneurship and international relations from the University of Pennsylvania.

He had already delayed his induction by a year.

“Boston is a great place to be as a young adult. I would have eventually returned to Mumbai, but probably in a couple of years,” he says.

A perfect storm awaited Shreevar back home.

This wasn’t the first time the Kherukas were on sticky ground. The family’s first glass manufacturing company, Window Glass Ltd, was set up by Shreevar’s grandfather BL Kheruka on the outskirts of Kolkata in 1962. It bled for the first 14 years, thanks to a price war among local manufactures, including Triveni Glass. The tide turned against Borosil again in the early 1990s, when global glass manufacturers like Guardian Industries, Asahi Glass and Saint Gobain set up manufacturing units in India and unleashed another price war.

On both occasions, the Kherukas stayed afloat by arresting costs.

Borosil was again found wanting in 2005-06 when global companies such as the Duran group, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Millipore, and Merck (Merck eventually bought Millipore in 2010) started making inroads into India. A string of other events also crippled Borosil’s production.

In May 2006, the Maharashtra government hiked electricity charges from ₹4.20 per unit to about ₹7.50. Electricity accounted for about one-fourth of costs at the Borosil Glass Works plant in Andheri, Mumbai, which mainly produced glass tubes, a crucial raw material for end products. “The increase in cost was more than the 15-percent margin we were making,” says Shreevar.

Attempts to increase production at the Andheri plant also came a cropper. First, the labour union declined to fall in line. Second, the state pollution control board denied permission to expand the plant, indicating that any activity entailing higher fuel consumption was a potential threat to nearby residences. An attempt to secure land near Roorkee in Uttarakhand, where several competitors had set up manufacturing facilities lured by excise benefits and cheap labour, also fell flat.

In effect, the Kherukas were simultaneously fighting a legal battle with the labour union, staving off competition and scouting for an alternative location to set up a plant, all the while ensuring a steady supply of raw materials. “The stress of managing monthly payroll and interest payment was very high. The time between 2006 and 2009 were very bad years,” remembers Shreevar.

He addressed the supply constraint by importing raw material from Europe and China, a move that has since become a permanent fixture in Borosil’s sourcing practice. “We were able to source tubes cheaper than the cost of production here. We had tried doing this around 2002-03, but the rates were much higher then,” says Shreevar.

An alternative site for the plant was also discovered, rather serendipitously, during one of his trips to Gujarat. It was a piece of unused family-owned land adjacent to the company’s Bharuch plant. Navigating the company through this protracted crisis was a turning point for Shreevar and the family. Pradeep says, “The challenges were real and he [Shreevar] really stood up to them. After that, he got entrenched in his role, taking the company up beyond that point.”

Meanwhile, Pradeep had succeeded in selling off the Andheri land to a real estate developer for ₹830 crore. The proceeds not only helped pay off debts, but also infused much-needed capital in the company. “The stars had finally aligned,” laughs Shreevar.

*****

The purple patch of the last five years has given the Kherukas enough confidence to take a few bold decisions. Borosil Glass Works, for instance, has shed its conservative garb to acquire distressed companies.

In January 2016, it announced the acquisition of Jaipur-based Hopewell Tableware, which manufactures opal dinnerware under the Larah brand, for ₹90 crore. In July 2016, it paid ₹27 crore for a 60 percent stake in Klasspack, manufacturers of glass ampoules and vials, to target the pharmaceuticals businesses. Borosil has since upped its stake in the firm to about 75 percent with an additional investment of ₹15 crore.

Hopewell is on track to clock ₹150 crore in sales in FY19, as against ₹48 crore in FY16 (when it posted a loss of ₹22 crore). Klasspack’s revenue increased from ₹28 crore in FY17 to about ₹37 crore in FY18.

“Of late, they [Borosil] have made significant investments. Not only consumer, but the laboratory equipment business—a niche vertical with better margins and less commoditisation—also did well,” says Abhimanyu Sofat, VP-Research at financial services company IIFL.

Despite initial traction, the consumer products business is fraught with challenges. While Borosil is a market leader in glass products, competition from relatively cheaper plastic and steel products manufactured by the likes of Tupperware, Cello, Milton and Signoraware is nipping at its heels. In opalware, Larah significantly lags market leader La Opala. Appliances is full of legacy brands like Bajaj, Prestige, Philips, Singer and Havells.

Ankur Bisen, senior vice president, Technopak Advisors, says, “A brand like Borosil, which is synonymous with kitchenware, might as well enter new categories such as appliances because entry barriers are low. In these categories, consumers want brand as a promise for quality. There need not be a product differentiator because there is only so much one can do with the available technology.”

However, Harminder Sahni, founder and managing director of consultancy firm Wazir Advisors, warns, “If products aren’t differentiated, it all boils down to price and availability.”

Shreevar treads with caution to ensure that brand Borosil isn’t diluted. For instance, Borosil did not immediately lend its name to Larah post-acquisition. “We invested about ₹70 crore and upgraded the plant to meet certain quality parameters. Now, the brand is called Larah by Borosil. This year, an exclusive Borosil range will be launched from the same production facility,” he adds.

Meanwhile, Gujarat Borosil, led by Pradeep, has been dealing only in solar glass since 2010, taking on Chinese manufactures. The firm will soon double its capacity from 180 tonnes per day to about 400 tonnes. “Solar glass has been doing very well despite severe competition from China. In raw material, power and fuel, packing material, we are over 30 percent cheaper than them,” says Shreevar, explaining that this allows the bsuiness to stay afloat even in the absence of subsidies.

*****

Historically, the Kherukas have been quite a giant slayer. Their acquisition of Borosil from New-York headquartered Corning is a case in point.

In the mid-1980s, the Kherukas were setting up a plant in Bharuch to run a fusion glass plant in partnership with Corning. A few crores were at stake. “At the eleventh hour, they sent a letter saying the technology has failed and they won’t pursue the partnership,” says Shreevar.

BL Kheruka dragged Corning to court. The audacity to challenge Corning speaks volumes about the family’s ambition and resilience, says Haigreve Khaitan, partner at law firm Khaitan and Co. His father, Pradip Khaitan, had advised the Kherukas on the case.

“Once they were convinced [of the legitimacy of the case], they left no stones unturned to get a compensation,” Khaitan says. “Many businesses of that scale would have given up, calling this a futile exercise. This reflects their commitment to the business.”

The Kherukas weren’t just brave, but also far-sighted. Instead of settling for a financial compensation, they convinced Corning to hand over its stake in an Indian company, Borosil Glass Works. Thus began a journey that has seen the Kherukas shed much sweat and blood.

Shreevar, however, believes his journey has just begun: “In FY20, we should hit ₹1,000-crore turnover at group level. That would be the starting point of some respectability as far as our brand is concerned.”

First Published: Feb 19, 2019, 11:55

Subscribe Now