How Aye Finance is making micro-lending profitable

Aye Finance found a crucial gap in the market for lending Rs 1 lakh to Rs 3 lakh to micro-entrepreneurs. Here's how they are helping MSMEs and building a resilient business for themselves

Mahinder Kumar has been in the business of manufacturing cricket balls since 1994. The Meerut-based businessman has a steady set of customers, but lacked access to capital to buy new equipment and hire more workers. In 2015, he turned to Aye Finance that was willing to offer a Rs. 150,000 loan to help him scale. Importantly, he got the loan within a week of applying. In the nine years since, Kumar’s sales have risen from Rs. 100,000 a month to Rs. 700,000 a month. “I haven’t felt the need to look elsewhere as their processes are transparent," says Kumar.

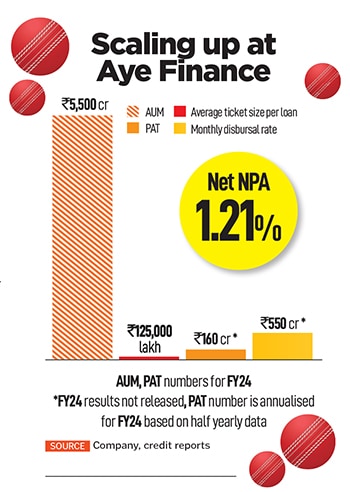

Kumar’s needs, distinct from those of large borrowers, form a huge opportunity set for lenders like Aye Finance that make loans in the Rs. 150,000 to Rs. 300,000 range. (Aye’s average loan size is Rs. 125,000.) Traditionally, this segment has been unable to tap into the formal credit ecosystem as lenders have struggled with credit assessment models. As a result, borrowers have been forced to rely on moneylenders and other informal sources of credit at usurious rates of 60 to 80 percent per annum.

Now, lenders like Aye Finance have taken the first steps at formalising credit to this segment. For them, the challenge is two-fold—getting the credit assessment right and administering these loans at a cost that makes it a viable business. The latter is done through the use of technology in everything, from loan assessment to collections.

Set up in 2014, Aye recently completed a decade and has disbursed loans worth Rs. 10,000 crore. They defined their target customers as businesses with a turnover of Rs. 20 lakh to Rs. 40 lakh per year. These are usually overlooked by banks as they lack formal accounts. But at 6.4 crore businesses, they present a large target market. Think of small traders, manufacturing units, restaurants, beauty parlours, service technicians, and one gets an idea of whom they lend to. While the last decade saw formal credit taking off for salaried employees, the hope is that this decade should see deeper penetration of credit to small businesses as technology makes underwriting and collections easier.

Aye ended FY24 with an assets under management (AUM) of Rs. 4,500 crore. This is a 55 percent jump from the previous fiscal and shows that the business has what it takes to scale rapidly. Its book has proven to be resilient with a gross NPA of 1.21 percent in FY24. Bad loans also held up well during the Covid shock. Profitability in the first half of FY24 stood at Rs. 82 crore and its net worth is about Rs. 900 crore, giving it ample room to grow. This is also when it may consider a listing. Its peers, Five Star and SBFC, listed at an AUM of Rs. 5,000 crore.

Aye ended FY24 with an assets under management (AUM) of Rs. 4,500 crore. This is a 55 percent jump from the previous fiscal and shows that the business has what it takes to scale rapidly. Its book has proven to be resilient with a gross NPA of 1.21 percent in FY24. Bad loans also held up well during the Covid shock. Profitability in the first half of FY24 stood at Rs. 82 crore and its net worth is about Rs. 900 crore, giving it ample room to grow. This is also when it may consider a listing. Its peers, Five Star and SBFC, listed at an AUM of Rs. 5,000 crore.

In 2014, when Sanjay Sharma, a career banker, sought to cater to the bottom of the pyramid businesses, credit appraisal for such small customers was unheard of. Credit bureau scores for individuals were just taking off, Aadhaar registration wasn’t widespread and few were willing to believe this could be done.

Sharma who was keen on making an impact knew he had to start slow and spend time understanding this segment. “In 2014, we estimated that there were 6.4 crore enterprises that we could cater to," he says. The challenge was in getting credit appraisal processes done.

The team at Aye spent time studying 350 micro entrepreneurs and came up with a few findings. First, there were no profit-and-loss statements. The business owners had a rough idea of what they made, their margins, the turnaround time, the cash conversion cycle, but were unable to offer anything formal to substantiate it. Second, once these businesses were studied, there was a way of arriving at the orders an entrepreneur could service by taking a look at proxies—like the number of employees or the average electricity bill. Margins were the same across similar industries as businessmen lacked pricing power. So, a shoemaker would make about the same money for the same volumes.

“Small businesses have income statements, but not balance sheets, and so don’t have the wherewithal to survive a downturn," says Vishal Sood, venture partner at Elevation Capital, which has been an investor in Aye since its initial days and invested $11.5 million (Rs. 95 crore) across four rounds in the company.

Aye collected and studied this data across a range of industries and customers. In this regard, its journey was similar to the path traversed by home loan companies that sought to lend to customers outside the salaried class. Gruh Finance, Home First and Aptus, among others, built models that allowed them to predict incomes across a diverse range of professions and then went about underwriting home loans. In the last decade, they’ve built franchises valued in excess of Rs. 15,000 crore, with a growth rate in excess of 20 percent a year.

Sharma thinks of this business as microfinance for micro enterprises, but without the joint lending group model. Catering to larger companies would put him in competition with lenders like Bajaj Finance that have a lower cost of capital and make it harder to compete. Small businesses will typically gravitate towards the lender that can offer them money quickly and are less concerned about the rate of interest as borrowing from moneylenders would be twice as expensive. The team at Aye focuses on fast turnarounds for loan applications.

The model relies on understanding the business economics of clusters and Sharma says the company has never left a cluster after entering it. Loans are administered through branches that are set up at a total cost of Rs. 4 lakh a month. This includes employee costs for eight loan officers and a credit officer, rent, electricity and so on. They break-even on an AUM of Rs. 3 crore. Once a credit officer validates, the application is sent to a centralised team that either approves or denies the loan. This and a digitised process are key to keeping costs down.

Currently, Aye’s competitive edge is threefold. First, is on the underwriting. The business has shown that it can weather storms and keep its credit costs low. The last three fiscal years have seen net NPA numbers at 1.37 percent in FY22, 1.28 percent in FY23 and 1.21 percent in FY24.

A short loan tenure means that any surprises on the asset front should be visible soon. “As an investor, I would want to see how the portfolio held up in the past during a credit event. They managed demonetisation and Covid spokes fairly well," says Kaushik Anand, partner at A91 Partners, an investor in Aye.

“Since the tenure of their loans is 18 to 24 months, any issue with the portfolio shows up in two years and hence the book is now fully recovered from the Covid impact."

Second is a diversified base of lenders. Sharma does acknowledge that the recent advisory from the Reserve Bank of India for lenders to go slow in lending for unsecured loans would have had some impact on bank funding. But he points to the fact that the company gets funds from banks and NBFCs, bonds as well as external commercial borrowings from development financial institutions.

A worker at a Meerut-based manufacturer of cricket balls. The propietor, Mahinder Kumar, took a loan from Aye Finance and was able to scale up his production and revenues

A worker at a Meerut-based manufacturer of cricket balls. The propietor, Mahinder Kumar, took a loan from Aye Finance and was able to scale up his production and revenues

Aye’s customer will accept a higher rate as long as the money comes on time. With a credit rating of A- from India Ratings, Aye is able to raise money at 10.75 percent. In addition, money can also be raised through securitisation and passthrough certificates.

Third is a technological backbone that allows the company to digitise processes. Lending and collecting in small amounts can be extremely time consuming. Manual processes take up too much time and can’t be done at scale for repeat customers. In fact, technology is also used extensively in the collections process—from deciding whom to call for late payments.

According to industry sources, Aye took money from CapitalG (Google Capital) at a lower valuation than other investors because it believed CapitalG would be able to advise them on their technological rollout better.

Aye ended the first half of FY24 at a profit run rate of Rs. 80 crore, according to data from India Ratings. This would take its return on equity to about 20 percent. (Aye hasn’t released FY24 numbers yet.) The business has a monthly disbursal rate of Rs. 550 crore a month and expects to clock a growth rate of 40 percent a year for the next three years. This should put it in a good position to list. Peers Five Star and Veritas (unlisted) quote at a book value of four times. With its current growth, Aye would be well-placed to list at these valuations.

First Published: May 17, 2024, 13:13

Subscribe Now