How MTR has stayed true to its Kannadiga core

Over 17 years after its acquisition by Norwegian company Orkla, MTR has stayed true to its core—a Kannadiga brand rooted in local culture, cuisine, and revenue. As it steps into its centenary year, it

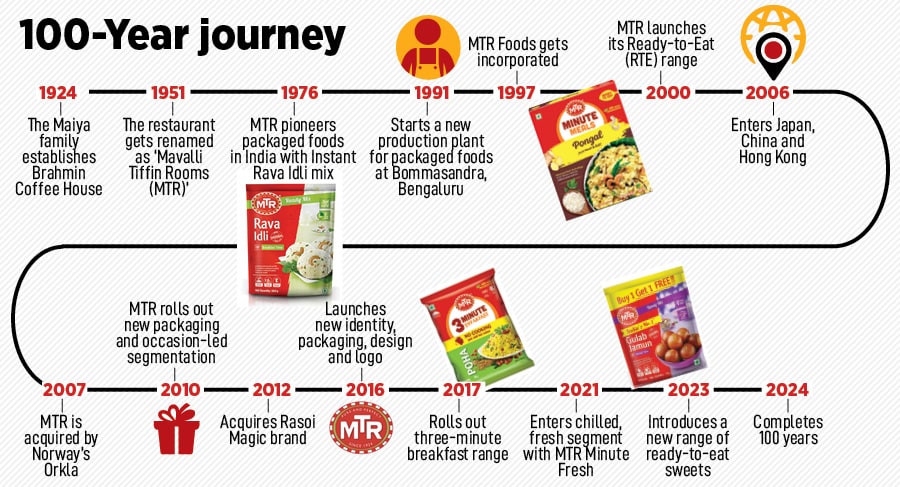

Sanjay Sharma was gripped with a comical predicament. “It was strange for a Punjabi to head a 99 percent Kannadiga business," recalls the chief executive officer of Orkla India, alluding to his role of heading spices and foods brand MTR as CEO in 2009. “I mean, we are two different cultures," says Sharma, who started his professional innings with Voltas in 1990 and managed Pepsi Snacks Foods (in the early 90s, Voltas used to be the distribution arm of Pepsi Snacks Foods). Over the next one-and-a-half decade, he had stints with Colgate Palmolive and Dabur, and, in 2009, Sharma wafted across the south of Vindhyas to Bengaluru to head heritage brand MTR, which traces its origin to 1924 and was acquired by Orkla in 2007.

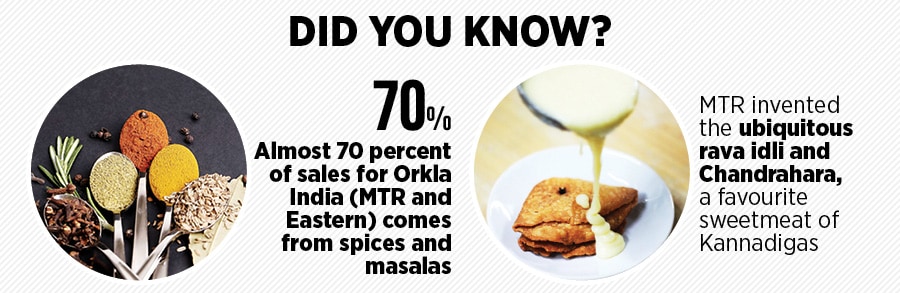

Two years after the buyout, Sharma was at the helm of a quintessential regional brand that prided itself in its rich cultural lineage and DNA. MTR—it invented the ubiquitous rava idli and Chandrahara, a favourite sweetmeat of Kannadigas—was synonymous with Karnataka. For Kannadigas, MTR was not a brand but an emotion. Sharma knew the context, the ask and the new task. “My biggest challenge was to change myself, respect the culture and know more about the company and people," he recounts.

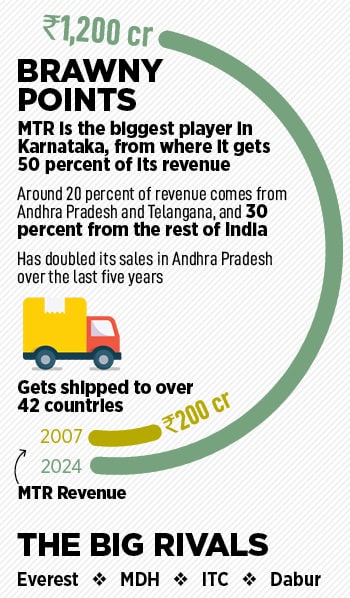

What also made the job intimidating was the way Sharma was wired. Voltas, Colgate and Dabur were national brands that drew power from their sweeping pan-India retail heft. MTR, in contrast, was largely confined to Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and a few adjoining Southern states despite its presence across the country and a few countries where it catered to the Indian diaspora. The top dog embraced the new reality, acknowledged the new business landscape, and factored in another reality which was the driving force behind Orkla’s acquisition of MTR, which had around ₹200 in revenue in 2007. “When Orkla bought MTR, it did not see a national business in it. It saw a regional business," he reckons. The Norwegian investment firm had a strong regional strand ingrained in its DNA: Buy and build local brands. With MTR in its fold, Orkla was unambiguous in its game plan: Go deep rather than spread wide.

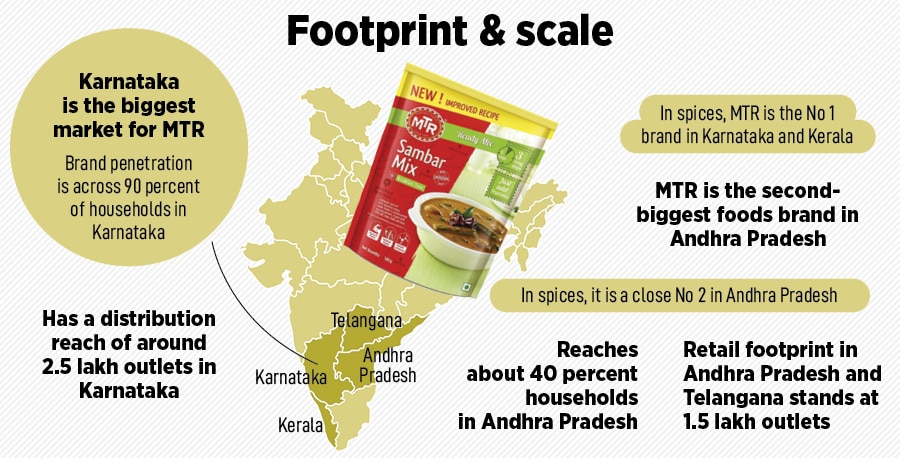

Back in 2007, MTR, undoubtedly, was a dominant regional player. In spices and masalas, it was the biggest brand in Karnataka. “We were the No. 2 brand in Andhra Pradesh. Both Karnataka and Andhra were our strong markets," he says, adding that MTR also had a national trophy to flaunt. It was the biggest player in ready-to-eat gulab jamun in India. Sharma had his task cut out: Dump national aspirations and keep MTR a strong regional player sharply focussed on Karnataka and adjoining states.

Back in 2007, MTR, undoubtedly, was a dominant regional player. In spices and masalas, it was the biggest brand in Karnataka. “We were the No. 2 brand in Andhra Pradesh. Both Karnataka and Andhra were our strong markets," he says, adding that MTR also had a national trophy to flaunt. It was the biggest player in ready-to-eat gulab jamun in India. Sharma had his task cut out: Dump national aspirations and keep MTR a strong regional player sharply focussed on Karnataka and adjoining states.

Seven years later, in 2016, another Punjabi from the land of chhole bhature and lassi was venturing into the territory of rava idli and ellu juice (sesame seeds milkshake). Sunay Bhasin too had his reality check. One of the first things he learnt was that sambar (a lentil stew), unlike idli, in South India tastes radically different from the one made in the North. Bhasin—he worked with Britannia, KFC and Pizza Hut, and joined MTR as chief marketing officer in 2016—had an erroneous perception about sambar. He thought sambar powders of all kinds and from all places would be the same. “Sambar would taste the same because sambar powder is the same. Right? Wrong," he says.

A few months into his new role, Bhasin was a transformed and enlightened soul. His sister from north India visited him and made a conventional request. “I want to eat South Indian. Please take me to a restaurant," she said. Bhasin looked bemused. “There’s nothing called South Indian. You have to be more specific about the cuisine," he replied, adding that even sambar is of multiple types in the state. “Every 100 to 150 kilometres, the taste of sambar changes," he says. If there are six parts of Karnataka representing distinct cuisines, there are five parts in Andhra Pradesh with similar traits. Food, culture and brands are intertwined, underlines Bhasin. One needs to appreciate and respect the nuances. “We did, and that’s our secret sauce," he adds.

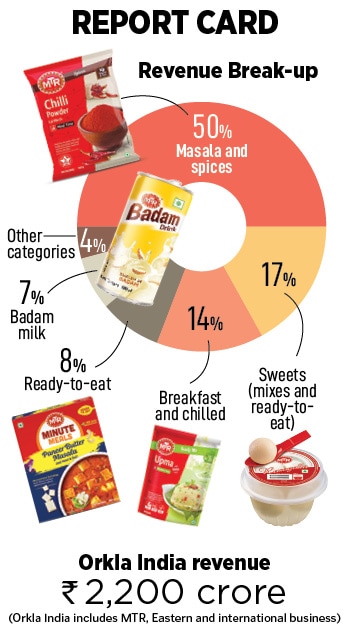

Fast forward to 2024. Over 17 years into its new innings under Orkla, MTR has stayed true to its core—a Kannadiga brand rooted in local culture, cuisine and revenue. It has grown its revenue from ₹200 crore in 2007 to ₹1,200 crore in 2024 is the biggest player in Karnataka, which contributes around 50 percent to its sales and has been growing at a furious pace in its second-biggest state: Andhra Pradesh. In terms of brand penetration, MTR covers around 90 percent of households in Karnataka and 40 percent in Andhra Pradesh. In terms of the sales mix, the numbers are skewed in favour of masala and spices which make up 50 percent of revenue, sweets (mixes and ready-to-eat) come next with 17 percent, breakfast, and chilled products are the third biggest with 14 percent, and ready-to-eat occupies the fourth slot with 8 percent. In terms of the overall revenue engine for Orkla India—which consists of MTR, Eastern (it was bought in 2021), and international business, and has a combined revenue of ₹2,200 crore—masala and spices again top the chart with a 70 percent contribution to the revenue.

Sharma is delighted with the performance. The CEO reckons that the brand has been served well by the philosophy of Orkla. “We don’t want to be a small fish in a big pond. We want to be a big fish in a small pond," he says, alluding to the approach the Norwegian company took after 2007. Orkla, he underlines, was crystal clear: If it’s an Indian business, it has to be run by Indians. “We don’t have Norwegians working in India," says Sharma. MTR’s interface with Norway is confined to the quarterly visit of the Norwegian board. The strategy worked. “The employees never felt the ‘Norwegian-ness’ of the company," he contends. Back in 2007, when MTR was acquired, nobody knew where Norway was. “People started looking at the map only after the acquisition," he smiles.

If downplaying the identity of the new owner came in handy, then conveying the ambition unambiguously also helped. “We wanted to remain regional. We didn’t want to become a large company in India," he says. In terms of the pantheon of the pan-India FMCG companies in size, MTR sits pretty at 42nd place. The talking point too remained MTR. “We never talked about Orkla. We made it clear that our purpose was to grow MTR, and make it bigger in its home states," he says.

If downplaying the identity of the new owner came in handy, then conveying the ambition unambiguously also helped. “We wanted to remain regional. We didn’t want to become a large company in India," he says. In terms of the pantheon of the pan-India FMCG companies in size, MTR sits pretty at 42nd place. The talking point too remained MTR. “We never talked about Orkla. We made it clear that our purpose was to grow MTR, and make it bigger in its home states," he says.

Curbing the national instinct also came due to a candid realisation. Sharma explains. MTR is not just a brand. It’s a strong emotion in Karnataka. Being a heritage brand, it has defined the food culture of the state. “Our primary job was to remain the cultural champions in the home state," he says. What this also meant was to revisit and realign the core of the company. Back in 2007, MTR had an extensive footprint across India. Sharma made a bold move. “I pulled back the footprint," he recalls. The market for processed food largely sits in the top 50 cities of India. “There is no point in taking our resources and spreading across 150 or 200 towns and cities," he says.

MTR 2.0 meant more of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Sharma restructured the strategy at two levels. First, he decided to have a sharper focus on the core geographies of the company. If around 75 percent of sales come from Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and the adjoining southern states, then one needs to go deep into these states, rather than spread wide across India. “We brought the focus back on Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh," he says, adding that MTR’s retail footprint in Karnataka now stands at 2.5 lakh outlets, and the equivalent number for Andhra Pradesh and Telangana is at 1.5 lakh. “We have doubled our sales in Andhra Pradesh over the last five years," claims Bhasin, who is now CEO of MTR. The brand, he adds, offers 145 products, has 400 SKUs (stock-keeping units), and over 3,000 recipes.

Not only geographies, but MTR’s product portfolio was also rejigged. Sharma pulled the plug on the ice cream business. “It did well, but was a low margin and low turnover business," he says. “Also, it was not the core of MTR." There was another realignment. MTR used to have a snacks vertical as well. “We realised it’s a low-margin business, so, we exited," he says.

MTR, Sharma underlines, will stick to its regional game plan. “Our strategy is to focus on the brand locally," he says, explaining why betting big on growing the business in select geographies makes sense. “Food is local. If you look at Karnataka, it has six different cuisines from six distinct regions," he says. In 2018, Sharma rolled out ‘MTR Karunadu Swada’, a unique food festival showcasing more than 100 forgotten dishes from six regions of Karnataka. If you go to North Karnataka, Sharma underlines, you will encounter peanut-based cuisine. If one travels to Mangaluru, one gets to taste Kundapur cuisine. Similarly, Coorg and South Karnataka have different flavours. “When food is regional, we believe that food brands too have to be regional and not national," he adds.

The heritage brand from Karnataka, reckon marketing and branding experts, has created a new playbook for managing acquisitions. One of the big strengths of a big brand is its ability to scale at a furious pace. “You buy to grow, and most of the new owners yield to the temptation of taking the acquired brand beyond the home turf," says Ashita Aggarwal, professor (marketing) at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. The acquired brand, she adds, is a trophy to be flaunted, and spreading it far and wide gives it bragging rights. “Orkla interestingly stayed away from this," she says. The new owners quickly realised the brand had a massive headroom for growth on its home turf. By some accounts, Karnataka’s population is equivalent, if not bigger, to the UK. “If you have bought the biggest food brand in Karnataka, it means you have bagged the biggest in the UK," she says.

The heritage brand from Karnataka, reckon marketing and branding experts, has created a new playbook for managing acquisitions. One of the big strengths of a big brand is its ability to scale at a furious pace. “You buy to grow, and most of the new owners yield to the temptation of taking the acquired brand beyond the home turf," says Ashita Aggarwal, professor (marketing) at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. The acquired brand, she adds, is a trophy to be flaunted, and spreading it far and wide gives it bragging rights. “Orkla interestingly stayed away from this," she says. The new owners quickly realised the brand had a massive headroom for growth on its home turf. By some accounts, Karnataka’s population is equivalent, if not bigger, to the UK. “If you have bought the biggest food brand in Karnataka, it means you have bagged the biggest in the UK," she says.

Another sensible move was to professionalise the organisation, which was founder-led in orientation, loyalties and vision. “It’s not easy to rewire an organisation, especially when you are not touching the core," says Aggarwal. What helped was having an Indian team run the show rather than imposing somebody from outside. “Orkla always had the remote control, but it never pressed the button," she adds.

Orkla’s Sharma, meanwhile, takes us back to 2009, and recalls his plight as the captain of the Kannadiga ship. Typically, when a new CEO joins, the organisation expects radical moves. In corporate lingo, such steps are known as layoffs. What compounded the problem for Sharma was his background. “Punjabis are known to be aggressive," he smiles, adding that for the first six months, he didn’t change anything. Sharma stayed calm, controlled his actions and mimicked the behaviour of Sadananda Maiya, the son of MTR’s founder, who remained in the system for two years after the acquisition. The first task, Sharma points out, for the CEO was to make a new blueprint. “It was clear that MTR has to be structured differently. It can’t be run as a family-led business," he says.

The big challenge was to undertake radical changes without disrupting the organisation. Retaining old-timers, hiring professionals, ringing in upskilling, maintaining the pace of innovation, and adding much-needed organisational pillars such as sales, marketing, supply chain and HR became the top priorities of the CEO. Around ₹200 crore was infused in a master plan to modernise factories and build infrastructure.

But what continued amidst the change was MTR’s commitment to the local culture, cuisine and tradition. Sample this. Recently, MTR created a water conservation capacity of 40 million litres in and around the Bommasandra area in Bengaluru. The message to the local community was: Namma Nela, Namma Jala. “When we bought MTR, we could have gone against the grain," says Sharma. “What we are today is largely because we went with the flow," he says, adding that MTR and Orkla are not going to tamper with a successful playbook. Despite plans to explore the public markets in India in 2025, MTR will keep its regional focus intact. “Orkla is the sun, and MTR is the moon. This is what drives our universe," smiles Sharma.

First Published: Jul 31, 2024, 12:21

Subscribe Now