How the Katkar family built Quick Heal into India's largest consumer antivirus b

Over the last three decades, the Katkar family battled formidable odds to build the company. Now, the next-gen is busy loading enterprising plans for the company

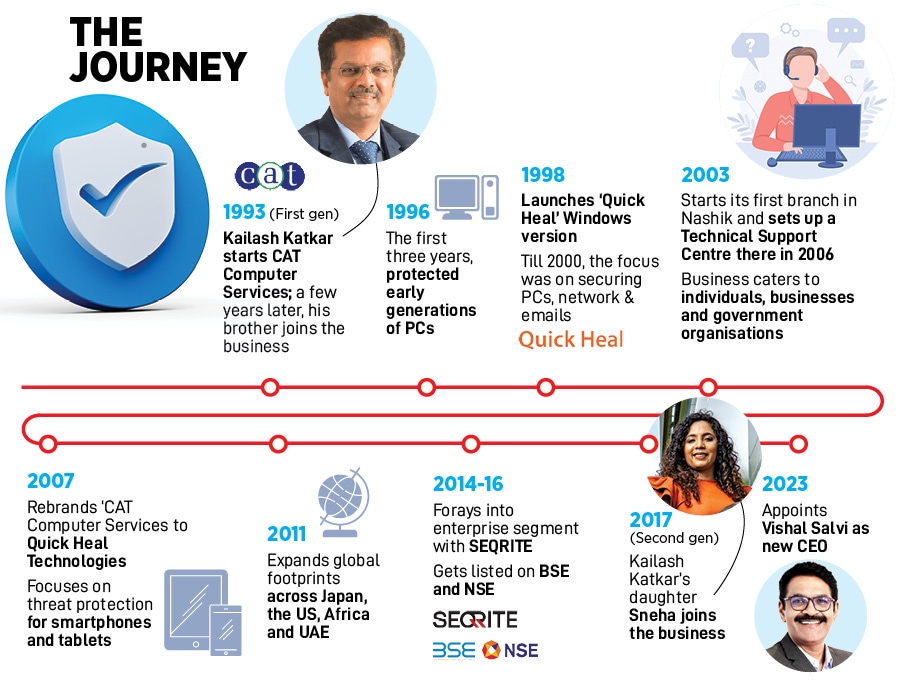

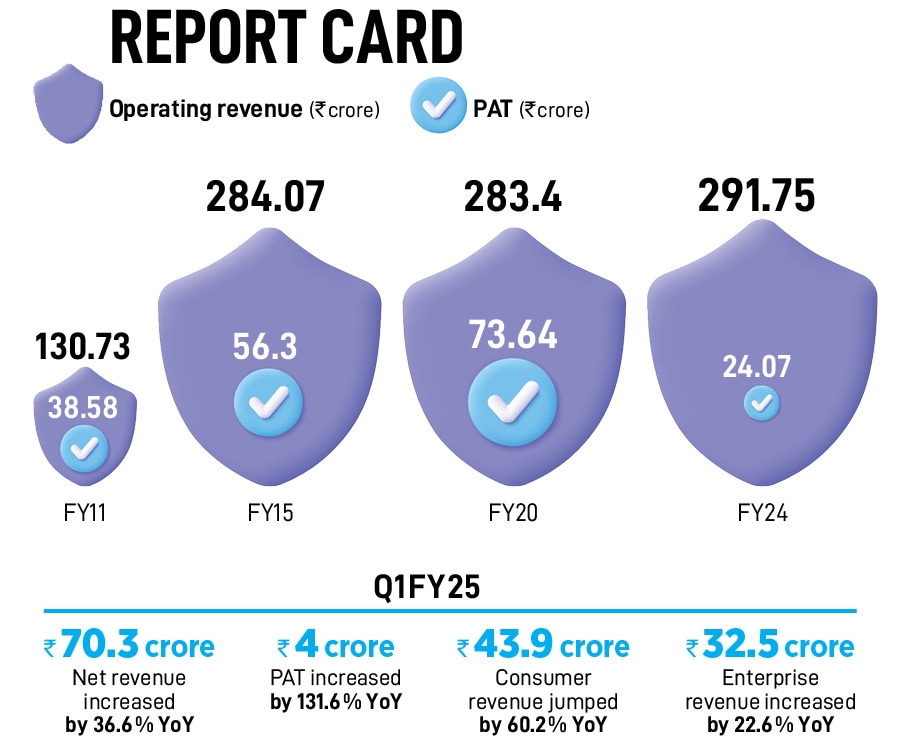

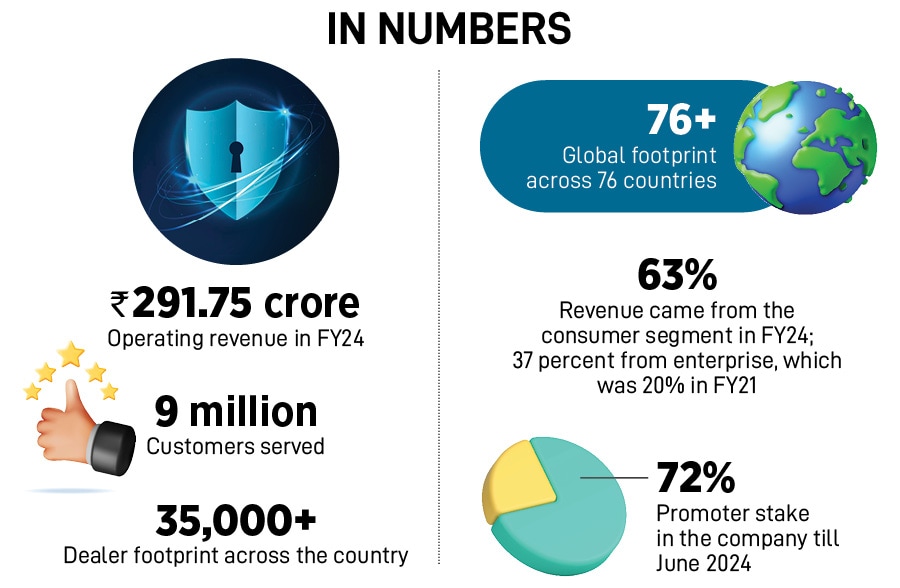

February 18, 2016, Mumbai. Kailash Katkar was getting jittery. His palms were sweating, his tight grip around the handle of the hammer started to loosen, and his eyes stared blankly at the gong. Signs of nerves for the first-generation entrepreneur? Well, it seemed so. What started as a calculator and computer repair business in Pune in 1993 morphed into India’s biggest consumer antivirus software company over the next decade. In March 2015, Quick Heal posted an operating revenue of ₹286.11 crore, a PAT (profit after tax) of ₹56.2 crore, and boasted 6.9 million active licenses across 80 countries. A year later, in 2016, a school dropout, who once worked for a stingy salary of ₹400 per month, was about to ring the bell at the stock exchange for a ₹250-crore IPO (initial public offering).

On the D-Day, though, Katkar appeared lost. On February 18, 2016, Quick Heal was getting listed and the founder looked anxious. “Dost kaisey problem create karenge (how can friends create problem)," he wondered. A son of the soil from Rahimatpur, an obscure village near Satara in Maharashtra, diligently built his life, and business, around trust. Katkar started CAT Computer, a computer repair and service company, in 1993. Two years later, his younger brother Sanjay Katkar joined the business and started giving the hardware venture a software makeover.

From repairing computers, the brothers started hunting for viruses inside computers. The soaring level of trust and bonding between the siblings was mirrored in the camaraderie and trust with thousands of channel partners—offline retailers and distributors—of Quick Heal. In FY15, around 86.67 percent of the business was generated via partners. “I trusted them for decades. How could they do so?" muttered Katkar, as he was about to hit the gong. “They can’t betray me," he rambled.

Interestingly, the warning signs, and symptoms of betrayal, were identified and flagged by Sequoia in the run-up to the IPO. “You are putting all your eggs in one basket," was the warning from the venture capital (VC) firm, alluding to the practice of offering high periods of credit to the channel partners: 60 to 90 days. “It’s too risky," reckoned the VC firm, which reportedly bought a 10 percent stake in Quick Heal for $12.8 million (around ₹60 crore) in August 2010. A few years later, when Quick Heal filed its DRHP (draft red herring prospectus), the risks were outlined in black and white. In FY14, the company made a one-time charge to its profit and loss account of ₹17.32 crore as an exceptional item for the provision created due to default by one of its distributors and fraud by an employee. “It negatively impacted our financial condition," the company mentioned in the draft IPO note, which also highlighted another red herring: Higher service tax liability, and tax proceedings.

Interestingly, the warning signs, and symptoms of betrayal, were identified and flagged by Sequoia in the run-up to the IPO. “You are putting all your eggs in one basket," was the warning from the venture capital (VC) firm, alluding to the practice of offering high periods of credit to the channel partners: 60 to 90 days. “It’s too risky," reckoned the VC firm, which reportedly bought a 10 percent stake in Quick Heal for $12.8 million (around ₹60 crore) in August 2010. A few years later, when Quick Heal filed its DRHP (draft red herring prospectus), the risks were outlined in black and white. In FY14, the company made a one-time charge to its profit and loss account of ₹17.32 crore as an exceptional item for the provision created due to default by one of its distributors and fraud by an employee. “It negatively impacted our financial condition," the company mentioned in the draft IPO note, which also highlighted another red herring: Higher service tax liability, and tax proceedings.

Meanwhile, at the IPO listing ceremony, the ‘risk’ came back to haunt Katkar. One of the former partners filed a legal suit against the company, alleging that Quick Heal didn’t disclose the share allotment made to his family and him. Though Katar was quick to rubbish the allegations, the upbeat IPO euphoria was sullied. Unfortunately, the bad omen coincided with a weak debut for the new kid on the listing block. Quick Heal plunged 20 percent over the issue price and the stock ended at ₹254 against the listing price of ₹321. A few days later, the stock tanked to ₹209, the lowest since its listing on the National Stock Exchange (NSE). The investor sentiments were subdued, and the company faced its first crisis post-listing.

Back in 1999, Quick Heal was staring at an existential crisis. The antivirus (software) part of the business was still in its early days, grappling with problems, and the bootstrapped venture of the Katkars was fast running out of money. “We were struggling to pay salaries," recalls Katkar. The younger one explains the problem. Though the software business had picked up, the uptick didn’t reflect in the revenues. Reason? The money was stuck with retailers and distributors who were notorious for delaying payments. There was little that the siblings could do to instill punctuality and discipline among the channel partners. “There was no wiggle room," says Sanjay.

Though distribution was fixed, there was another loose end: Capital. The venture capitalists (VCs) were missing in action, PEs (private equity players) too were not prolific, and the traditional form of lending—banks—didn’t have the appetite to bet on a business that didn’t have a physical product. “During the early years, we were dependent on Kailash’s hardware (repair and maintenance) business to fund the venture," recalls Sanjay. But when the inflow from the hardware business petered out, the venture slipped into trouble.

The wear and tear started taking a toll. The disagreement between the brothers flared. A few blocks away from their nondescript shop in Pune, the siblings found an arena—a spacious, empty playground—to argue, quarrel and play the blame game. “Almost three to four times we decided to quit," recounts Katkar. There were times when there was an explicit agreement between the brothers to fold the business and start life from scratch. What this meant was Katkar would resume his hardware venture and Sanjay would find a job, and fund the repair and maintenance business.

Interestingly, nobody honoured the commitment. After every fight, the brothers would get consumed by their overwhelming love for each other and decide to give their fledgling venture one more chance. “Thoda do mahiney aur rukte hai kya (can we wait for another two months)" was how every disagreement ended. Every extension of two months meant 60 more days of operational expense. That’s when Katkar’s wife chipped in and started a bakery shop to help the family tide over the crisis. The gambit paid off. From ₹3,000 turnover per day during the initial days, the shop started churning out ₹30,000 to ₹35,000 per day in a few weeks. The Katkars dug their heels in, and Quick Heal got a new lease of life.

As one problem got buried, more sprang up. The first revolved around hiring. Crippled by finances, the Katkars couldn’t hire the best talent in town. Quick Heal became the choice for software engineers who couldn’t find a job at campus placements. The handicap, however, turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Sanjay got employees who were not snooty, didn’t feel entitled, and were open to being trained. But there was a small problem. After getting skilled, the employees would leave after a year or so, and the Katkars couldn’t match their fat salaries. Attrition was a burning issue, and the brothers did their best to douse the fire.

There was fire-fighting to be done on another front. Once in the market, Quick Heal had to take on the big boys of antivirus. The problem was taxing on multiple counts. First, it was a lop-sided fight. MNCs had pedigree, a longer operating history, a larger customer base, and extensive international operations. They also had a bigger sales team, expansive marketing budgets, and a larger research and product development team. Second, the advertising blitzkrieg by the bigger players gave them massive eyeballs and relegated Quick Heal beyond consumer consideration.

Third, the desi challenger brand had to contend with a bunch of equally spirited regional homegrown vendors who played price warriors. Fourth, Quick Heal started with a niche—home buyers and users of computers. As competition intensified, the rivals started offering free software or bundled it free with other products. Quick Heal had not diversified its user base and missed out on small and medium businesses, enterprise customers, educational institutions, government agencies and departments. A depleted armoury hurt.

The brothers decided to take the fight head-on. “The biggest question was ‘us’ versus ‘them’, and we tried to prove our differentiation," recalls Sanjay, who spearheaded the qualitative fight. The first big edge emerged out of the consumer insight that antivirus updates added to the woes of users who already grappled with patchy internet connectivity. The users had to restart the download every time the connectivity was restored. Quick Heal came up with a solution. “We ‘resume’ and don’t ‘restart’," proclaimed the first-generation entrepreneur, alluding to the tech superiority of his product that bypassed the vexing problem of starting from scratch. The brothers loaded their product with more features that were suited to Indian needs. “We offered support and services in regional languages," says Katkar.

The next turning point came in 2010. The business was established, cash flow issues were a thing of the past, and Quick Heal had emerged as the biggest consumer antivirus player in India. VC firm Sequoia Capital evinced an interest to invest in the venture. The siblings, however, were least interested. They didn’t need the dollars. Interestingly, the brothers never left the table and realised the need to have venture capital to expand, add more heft to their play, and take on their rivals aggressively. In August 2010, the VC firm invested, and as expected, the pace gathered steam. The family-run company was gradually making a transition to a family-led company. The task was tough. Katkar explains. “It took Sequoia over a week to make me realise the need to have a CFO (chief financial officer)," he smiles. “I thought finance and accounts were the same."

The next turning point came in 2010. The business was established, cash flow issues were a thing of the past, and Quick Heal had emerged as the biggest consumer antivirus player in India. VC firm Sequoia Capital evinced an interest to invest in the venture. The siblings, however, were least interested. They didn’t need the dollars. Interestingly, the brothers never left the table and realised the need to have venture capital to expand, add more heft to their play, and take on their rivals aggressively. In August 2010, the VC firm invested, and as expected, the pace gathered steam. The family-run company was gradually making a transition to a family-led company. The task was tough. Katkar explains. “It took Sequoia over a week to make me realise the need to have a CFO (chief financial officer)," he smiles. “I thought finance and accounts were the same."

Another moment of truth came when the need for a CEO was felt. The brothers were nudged by the market, analysts and industry observers to rope in an outsider. A consulting company was hired to make a blueprint, and Vishal Salvi was appointed CEO in July 2023. A former Infosys biggie, Salvi had close to three decades of experience in information technology and cybersecurity. Over a year later, Katkar explains why the move came at the right time. “We wanted to shatter this perception of Quick Heal being a promoter-driven company," he confesses. What also sped the professionalisation drive was a humbling reality accepted by the brothers. “We had done this journey from 0 to 1. And I can [or can’t?] do this ‘start from scratch’ again and again," he says, adding that the journey has to go beyond 1.

Outsiders, along with a new set of insiders, play a crucial role in the ‘1 to 10’ journey. Katkar’s daughter Sneha has been learning the ropes over the last few years. She started with the B2B side of the business, and now takes care of the consumer product portfolio. The next-gen, underlines Katkar, has the firepower, passion and vision to drive the company ahead. “She [Sneha] is more analytical in approach, and along with the professionals, is best equipped for a ‘1 to 10’ journey," he says.

Sneha contends that she has inherited the best of genes from her family. “I have closely seen their journey, their highs and lows," she says, adding that Quick Heal has been diversifying to mitigate the headwinds in the consumer software market, and has invested disproportionately in the enterprise business over the last few years. “The results have started to show," she says.

Marketing analysts are impressed with the timely makeover of the company. “That (focus on enterprises) was the need of the hour," reckons Rajan Gahlot, assistant professor (department of commerce) at the University of Delhi. “The brand and the family needed to upgrade their play," he says, adding that beyond a point, family businesses have to graduate and take the next big leap in their journey. “From family-run it has to be family-led," he says. Gahlot, though, adds a word of caution. “It’s tough for families to give up control. The Katkars must walk the talk and let the professionals manage the show," he adds.

Katkar underlines that there’s no U-turn. “We trust the process, the business and the family," he says.

First Published: Aug 30, 2024, 15:48

Subscribe Now