First General Motors, Citibank and now Disney; why do MNCs fail in India?

Exit from the India market by multinationals is often on account of problems in home territory or failure to segment the Indian market correctly

If recent news reports turn out to be true, India has lost its magic for Disney. The world’s largest entertainment company could pare down its operations in India or call it quits entirely. On the table is a stake sale of its Star India operations as well as Disney+ Hotstar, the streaming app.

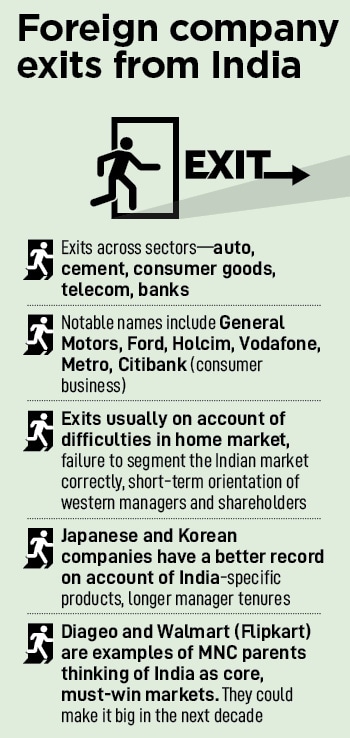

Given the quality of what is on offer, Adani, Sun TV and Blackstone are said to be interested and reportedly willing to pay a premium. But Disney’s exit as well as the exits of a host of multinationals (MNCs) over the last few years beg the question: Are these departures on account of the failings of the Indian market or are they the result of a failure on the part of these companies to operate successfully in a market as diverse as India.

The Ministry of Commerce and Industry, in reply to a December 2021 question in Parliament, had said that 2,783 foreign companies ceased operations in India between 2014 and November 2021. But it also pointed out that there were several MNC subsidiaries setting shop in India on account of the production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes. In addition, global service companies were increasingly locating their back offices to India.

India also remains a promising market for those who have worked at understanding its 1.4 billion consumers. With a per capita purchasing power parity income of $7,130 per person, there is enough space to operate in. But first, let’s take a look at some notable failures to understand whether recent exits have been on account of the Indian market or otherwise.

Manish Chokhani, director at Enam Holdings, dismisses the notion of MNC exits on account of the failings of the Indian market. “This seems to be a very narrow view of things," he says. The opportunity in the Indian market has prompted several companies to enter in the manufacturing and services space, he argues. For a Ford exit, there is an SAIC entry. For a Citi exit, there is DBS expanding. The list goes on and each headline-grabbing exit in the recent past can be attributed to problems with that company.

Take the case of Holcim’s exit from India. The Swiss building major sold its India subsidiaries ACC and Ambuja to the Adani Group in 2022 for $6.4 billion. While there was some commentary on a large multinational exiting India, the real reason was the move away from cement to ready-mix concrete by the company. The company says, “Holcim’s innovative ready-mix concrete solutions reduce CO2 footprint, costs, speed of construction and improve the energy efficiency of buildings." In addition to being higher margin, ready-mix concrete also allows it to fulfil its ESG metrics. Recent news reports of Heidelberg seeking an exit should be seen in this light.

Take the case of Holcim’s exit from India. The Swiss building major sold its India subsidiaries ACC and Ambuja to the Adani Group in 2022 for $6.4 billion. While there was some commentary on a large multinational exiting India, the real reason was the move away from cement to ready-mix concrete by the company. The company says, “Holcim’s innovative ready-mix concrete solutions reduce CO2 footprint, costs, speed of construction and improve the energy efficiency of buildings." In addition to being higher margin, ready-mix concrete also allows it to fulfil its ESG metrics. Recent news reports of Heidelberg seeking an exit should be seen in this light.

While the cement industry is highly fragmented, it is even in consolidated businesses that MNCs have found it hard to build a meaningful presence. When Ford and General Motors entered India in 1997, Tata Motors and Mahindra & Mahindra had not even started making passenger vehicles. Today Tata Motors and Mahindra are the number two and three carmakers in India, while Ford and General Motors have exited their India operations.

A former industry veteran, who declined to be named, points out to the fact that the companies failed to bring in the right products or build a wide dealer network in India. By the time they brought in India-specific products, the Korean and Japanese carmakers were already giving them tough competition and it became hard to compete. “General Motors also chose to focus on China and pulled back resources from India to do that," he says. Meanwhile, sales of passenger cars and utility vehicles crossed the 2 million-mark in the first six months of FY24 (till September-end) the highest ever.

The failure of General Motors and Ford also provides a ringside view on how they failed to segment the Indian market properly. Initially their cars, the Ford Escort and Opel Astra, focussed on what was then-known as the D segment—cars priced at Rs8 lakh and above, and accounted for the smallest slice of the market. They did not make cars for what marketers call the “belly of the market", the 100 million consumers that buy Android phones (and not Apple phones), and Maruti or Hyundai cars. By the time the Ford Figo or Chevrolet Beat came, the market had been taken away by the Alto and Santro, and later i10 models.

Sanjiv Mehta, former chief executive of Hindustan Unilever, has regularly said that India should be thought about as several mini markets and not one giant market. As a result, Hindustan Unilever’s ‘winning in many India’s’ allows them to focus only on specific sub-segments and geographies.

“A challenge for foreign banks is that the time for any competitor, local or foreign, to replicate and introduce a me-too product has narrowed significantly, thereby reducing the time available for them to achieve a quick payback through initial monopolistic pricing. This elongates payback periods and depresses returns that also need to be adjusted for hedging costs of the capital."

“It is unlikely that the headquarters of most of the foreign banks will continue to have the kind of abiding commitment to India that such capital deployment would entail, especially given the volatility of an uncertain local and global macro environment," he adds.

An additional issue some multinationals face is the short-term orientation of managements in their home countries. “Indeed, short-term EPS focus and stock-based compensation drives most Anglo-Saxon companies. Note the longevity of the German and Scandinavian and Japanese/Korean companies in India," says Chokhani.

The capital-intensive space of telecommunications, foreign companies have had a mixed experience. In the previous decade, when there were 12-14 telecom operators such as Etisalat, Tata Docomo, Aircel, MTS India, Videocon Telecom, BPL and Vodafone India, among others, it was actually a defined oligopoly and India was trying to create a perfect competition structure, which has not succeeded in other markets.

Telecom experts have often said while India appears to be a large market, it is not a very deep one. The number of people who can spend a top dollar are very few. From a digital commerce perspective, around 80 million Indians transact on digital commerce while the figure is 10x of that, 884 million in China.

The chaos in the telecom market happened when India was transiting to 3G technology from 2G. But several of the telecom operators at that time were capital starved then.

“All capital-hungry industries, particularly telecom, which is a long-term investment game, cannot scale up without foreign capital," a top telecom executive says on condition of anonymity.

Vodafone has always worked in markets where it did not need to second-guess the direction the market would take or how regulators or policymakers would act. The dispute over the retrospective tax legislation with Indian authorities was a chapter to forget.

Large telecom global giants are unlikely to set up greenfield projects in India. Even to speculate a takeover of the loss-making Vodafone Idea, a foreign investor would need to agree to write off all the debt which Vodafone Idea owes to the government and then be ready to pump in fresh capital of near $10 billion or more to seriously challenge the existing rivals Reliance Jio or Bharti Airtel.

Indian telecom companies have fared well in terms of servicing, even when the mobile telecommunications space was overcrowded with 12-13 players between 2012 and 2018. But from a products and solutions perspective, foreign players such as Nokia, Huawei, Samsung, Oppo and Vivo have dominated the Indian markets, as they owned the technology.

In the end, the markets in the US or UK don’t reward their managers for building long-term winners in emerging markets like India. Most acquisitions attract eyeballs for their hype—Disney acquiring Fox with a huge value for Hotstar, or Walmart acquiring Flipkart to checkmate Amazon. These excite analysts on Wall Street. However, as India is still sub-5-10 percent for most Fortune 500 companies, any ripple in the home market causes a reallocation of resources to fortify the mainstay home market. Citibank abandoning its affluent Indian clients selling out to Axis Bank is one recent example.

On the other hand, there are examples of western companies working to make India their core market. Diageo and Walmart (Flipkart) are good examples. Both are expending resources and time in putting together the building blocks. The next five to 10 years could well see Indian executives from these companies go on to lead substantial businesses in the global parent—something that has rarely happened except in the case of Unilever. Till then, expect many years of a hard slog for foreign companies looking to get their India strategy right.

(Additional reporting by Salil Panchal)

First Published: Oct 12, 2023, 12:43

Subscribe Now