Good news: Rupee rides out the Covid-19 storm

The pandemic-induced slowdown is the first time the Indian currency has not depreciated in a crisis

Image: Shutterstock

In 2008, during the global financial crisis, the Indian rupee depreciated by 25 percent in six weeks. Capital flows had been hit and exports were down. The US dollar reigned, and gold rallied as a safe asset. The net result was a 25 percent depreciation from Rs40 to the dollar to Rs50 at the end of 2008.

The intervening years have seen the rupee lose its value against a host of currencies (it moved from Rs50 to Rs75 to the US dollar between 2010 and 2020). High oil prices in the early part of the decade were to blame, as was a tightening in US interest rates—the US Federal Reserve signalled intentions to hike rates too. But at the same time the rupee held its own against emerging market competitors—its BRIC counterparts, Brazil, South Africa and Russia, whose economies are built on commodity exports.

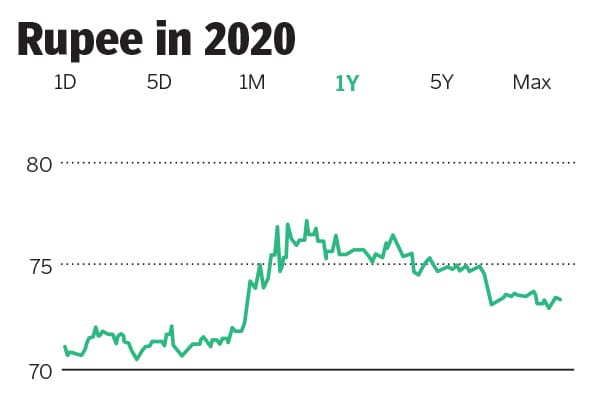

But as India entered the Covid-19 crisis, the previous depreciation playbook did not kick in. A host of factors resulted in the rupee holding its own against the dollar. From January, it has seen a mere 2.8 percent depreciation to Rs73.5 to the dollar. While this is equally on account of the dollar’s weakness, it also points to an emerging strength in the rupee, which should stand us in good stead in the years to come. The flipside is a strong currency being bad for exports—in particular, textiles, gems and jewellery, where countries typically lack pricing power. (IT exports are less price sensitive.)

Dollar Weakness

One clear plus point of the Covid-19 crisis was the fact that global central banks reacted early and decisively. This helped in stabilising financial markets and also gave investors the confidence that the government had their back. With a ready blueprint—interest rates cut, swap lines with other central banks set up—global central banks knew what they had to do.

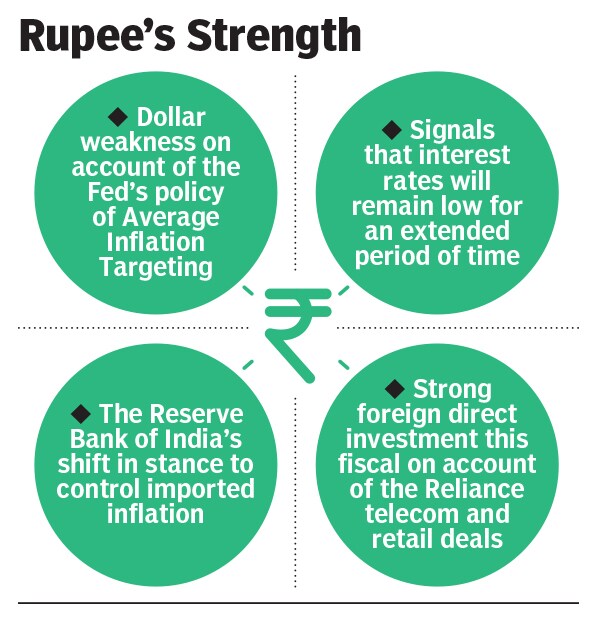

But the key difference this time is the average inflation target that the US Federal Reserve has adopted. “That is a game changer as they are signalling low interest rates and an expanding balance sheet for a long time,” says Anindya Banerjee, vice president (interest rates and currency derivatives research) - PCG, Kotak Securities.

In the previous crisis, while rates stayed low for four years, the Fed had never signalled that intention at thebeginning. The Fed’s inflation target has been set at 2 percent. The present difference between the US’s 10-year bond yield and India’s is 5.2 percent, making it worth the currency risk that investors take in when buying Indian bonds. An added attraction for yield-hungry investors is that India has never defaulted on its sovereign debt, and that there is now about $15 trillion in assets yielding negative returns mainly in Europe and Japan. “The rate differential between the US and Germany (two major markets for global bond buyers) is at a historical low,” says Abhishek Goenka, chief executive at IFA Global, which advises companies on the forex strategies.

The next few weeks are expected to see the announcement of an additional $2 trillion stimulus package by the US government, and this could increase pressure on the dollar.

Rupee Strength

On the Indian side, the crisis has shown that with a little bit of good fortune, a crisis can be effectively managed. This was the first time when both global demand and supply collapsed at the same time. This gave the Reserve Bank the leeway it needed to protect the rupee.

First, oil prices dropped rapidly and have stayed low. At the start of the year, Brent crude quoted at $59 a barrel. At present, it quotes at $42 a barrel, allowing India to reduce its oil import bill of $115 billion (Rs880,000 crore) by a third—and saving about $40 billion in foreign exchange. Second, low demand meant low imports, and the current account hit a surplus of $19.8 billion in the April-June quarter. There was also the $20.2 billion (Rs152,000 crore) that Reliance’s telecom arm raised.

With imports low, the Reserve Bank took a call to reduce imported inflation by keeping the rupee strong. “They decided to fight inflation through the rupee and not through the supply side,” says Goenka. It did this by selling dollars in the spot market and buying forward contracts, thereby reducing the premium. This sent a strong signal to traders that the government would not allow an uncontrolled depreciation in the rupee.

Another reason was that a depreciating rupee would impact foreign exchange reserves and the RBI’s balance sheet negatively, and not allow it to pay a sizable dividend to the government at the end of the fiscal year. In a cash-strapped year, the government needs all the help it can get.

As world economies resume activity and trade picks up, it remains to be seen where aggregate demand in the Indian economy settles. A high current account deficit could see the rupee depreciate again—it is then that the government’s resolve will be tested, as defending one’s currency has typically been a losing bet for most sovereigns. “While there is no one-size-fits-all in a consumer-led economy like India, a strong currency is good as it improves the purchasing power of households,” says Banerjee.

First Published: Oct 20, 2020, 14:14

Subscribe Now