The Reserve Bank of India’s year-long battle to rein in inflation—within its target of 4 percent with a margin of plus or minus 2 percent—is showing some results. In May, retail inflation cooled off to a 25-month low at 4.25 percent from 7.04 percent in the year-ago period. But despite the recent ‘moderation’ in price levels, the central bank’s war against inflation is far from over. There are concerns about higher government spending in the run-up to elections and the impact of extreme weather conditions on food prices.

“Uncertainties on the inflation outlook for H2 FY24 have not abated," RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said as per the minutes of the June MPC meeting. “The spatial and temporal distribution of the south-west monsoon in the backdrop of a likely El Nino weather pattern needs to be watched carefully, especially for its impact on food prices. Adverse climate events have the potential to quickly change the direction of the inflation trajectory."

Das also cautioned that geopolitical tensions, uncertainty on crude price trajectory and volatile financial markets pose further upside risks to prices. “These considerations warrant close monitoring of the evolving price dynamics," he said.

The growth picture looks brighter but has shades of grey: “From a cyclical standpoint, the next 6-12 months we see a slowdown ahead for the Indian economy. We expect FY24 GDP growth of 5.5 percent versus 7.2 percent in FY23. Past episodes of global downturn have disrupted not just India’s export cycle, but also its capex cycle. Meanwhile, the lagged effects of the RBI’s rate hikes have also yet to reflect on domestic growth," Sonal Varma, managing director, chief economist-India and Asia ex-Japan, Nomura says.

Government spending and the strongest quarter-on-quarter investment growth in 23 years pushed real GDP to 6.1 percent in the January-March quarter and 7.2 percent for FY23. In May, manufacturing PMI rose to a 31-month high of 58.7 from 57.2 in the previous month.

In short, according to the Reserve Bank’s rate-setting panel, urban spending remains robust and rural demand is improving, though unevenly, fiscal consolidation is ongoing, and domestic macroeconomic fundamentals are strengthening—economic activity is showing resilience, inflation has moderated, the current account deficit has narrowed, and forex reserves are comfortable. “The latest prints of growth and inflation indicate a Goldilocks scenario, with growth higher and inflation marginally lower than anticipated, this is telling us that our cumulative actions taken so far are working in the right direction," RBI’s executive director Rajiv Ranjan says. “It needs to be acknowledged, however, that knowing when to stop is hard."

And this is precisely why all six members are not on the same page.

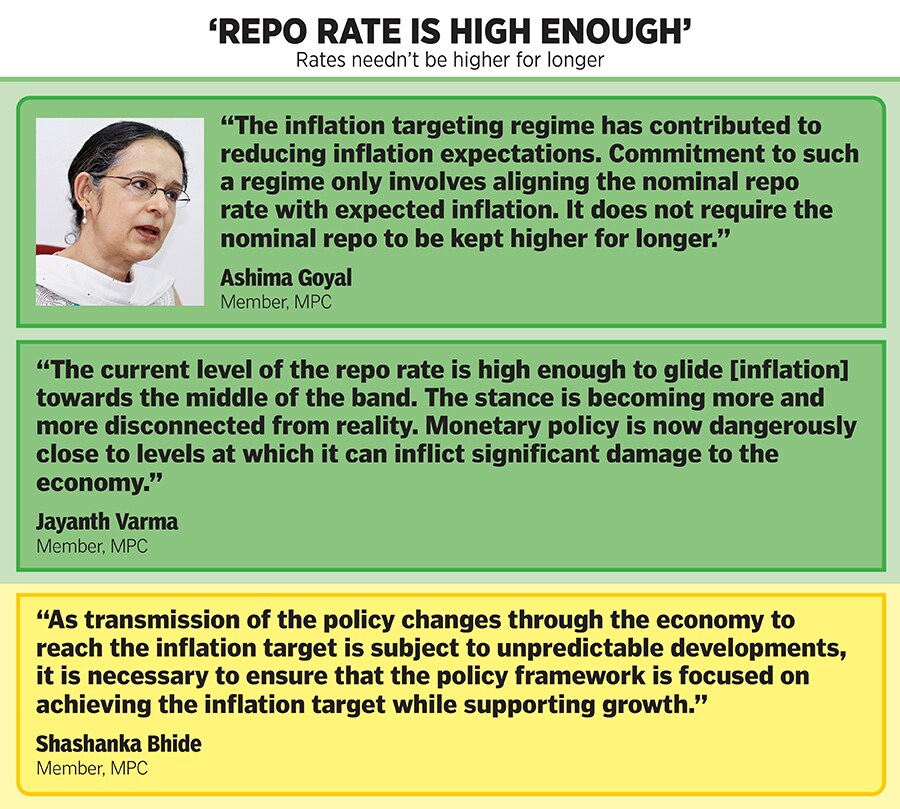

Repo rate is high enough

Broadly, the external members of the MPC, Shashanka Bhide, Ashima Goyal and Jayanth Varma, believe it is time for the rate-setting panel to loosen the grip on the economy to rekindle animal spirits and boost the nascent signs of economic recovery because inflation isn’t as big a threat as it was in the previous quarters.

Goyal highlights that GDP growth declined from 9.1 percent in FY22 to 7.2 percent in FY23 even as inflation moderated into the tolerance band although it isn’t firmly on the path to the target yet. However, Goyal argues, “It is clear that core inflation is neither persistent nor broad-based. Inflation was higher for so long because of multiple supply shocks."

![]() She adds that the quick succession of repo rate raises has brought the real repo rate to near equilibrium levels which has prevented over-heating as well as over-tightening of demand and helped to anchor inflation expectations as the slowdown and pause was all well-timed.

She adds that the quick succession of repo rate raises has brought the real repo rate to near equilibrium levels which has prevented over-heating as well as over-tightening of demand and helped to anchor inflation expectations as the slowdown and pause was all well-timed.

“As expected inflation falls, however, it is important that real repo rate does not rise too high. This is what happened in 2015 as international oil prices fell, damaging the economic cycle. Research suggests that the inflation targeting regime has contributed to reducing inflation expectations. Commitment to such a regime only involves aligning the nominal repo rate with expected inflation. Such action, together with the greater impact of official communication in emerging markets, is adequate to bring inflation to target as the effect of shocks dies down. It does not require the nominal repo to be kept higher for longer," she asserts.

As in the past couple of meetings, Varma had scathing remarks for the panel’s insistence on not changing its policy stance to send out a clearer signal on the outlook for rates: “With every successive meeting, this stance is becoming more and more disconnected from reality. Based on the forecast inflation for 5.1 percent for FY24, the real repo rate is now almost 1.5 percent. In other words, monetary policy is now dangerously close to levels at which it can inflict significant damage to the economy."

According to Varma, the current level of the repo rate is high enough to keep inflation below the upper tolerance band on a sustained basis and also glide it towards the middle of the band. “However, there are significant risks to both inflation and growth," he adds.

Also, in contrast to most members, Bhide isn’t as worried about the impact of extreme weather conditions on food prices. “The normal monsoon forecast by the Indian Meteorological Department, despite the emergence of the El Nino phenomenon, would be supportive of agricultural growth," he says. He adds that the impact of increase in policy rate between May 2022 and April 2023 by 250 basis points and other economic policy measures have been crucial in anchoring price expectations. “As transmission of the policy changes through the economy to reach the inflation target is subject to unpredictable developments, it is necessary to ensure that the policy framework is focused on achieving the inflation target while supporting growth," he notes.

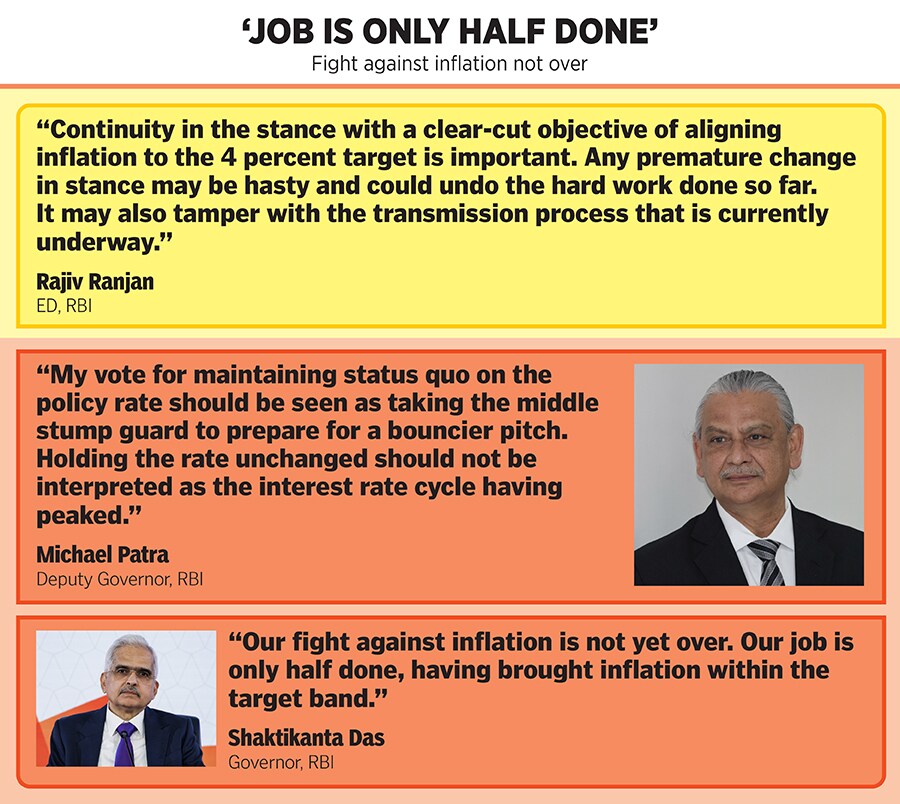

Job is only half done

The three RBI members, Rajiv Ranjan, Michael Patra and Shaktikanta Das, aren’t as optimistic and feel the pause in rate hikes doesn’t necessarily indicate an end in the rate hike cycle.

“If policy makers continue tightening until inflation falls as much as they want, they are likely to go farther than they need to," Ranjan says. “Notwithstanding this, it is important that we do not drop our guard against inflation, especially when we are still away from our primary goal of aligning inflation to the 4.0 percent target. Any premature change in stance may be hasty and could undo the hard work done so far. It may also tamper with the transmission process that is currently underway. Recent actions of some advanced economies reverting to rate hikes after a pause need to be kept in mind."

![]()

Patra agrees that monetary policy needs to remain in ‘brace’ mode to ensure that pressure points from supply-demand mismatches don’t offset favourable base effects in the second half of FY24. “My vote for maintaining status quo on the policy rate should be seen as taking middle stump guard to prepare for a bouncier pitch. Holding the rate unchanged should not be interpreted as the interest rate cycle having peaked, but as a period of careful evaluation of a decision on the extent of additional policy tightening, if needed," Patra explains.

Patra calls the pause a part of continuous learning about the underlying structure of the economy with new information until the next meeting of the MPC, and not a prolonged pause. “Headline inflation is edging down towards the target, but it is still well above it and the balance of risks suggests that it will go up in coming months before it comes down," he adds.

RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das underlines the need to undertake a forward-looking assessment of the evolving inflation-growth outlook which makes any definitive forward guidance on the future course of action in a rate tightening cycle difficult. “Our job is only half done, having brought inflation within the target band. Our fight against inflation is not yet over."

Overall, economists and analysts do not expect a rate cut until December. A few, however, are hopeful that the RBI will spring a surprise earlier. “We expect the RBI to use FX reserves to deal with currency pressures while monetary policy focusses on inflation-growth dynamics. As the Fed pauses, domestic core inflation cools, domestic demand slows down and the current account balance improves due to lower oil prices, we expect the RBI to prioritise domestic factors over the Fed. Our view is that the rate easing cycle in India will begin much earlier than is currently expected by the consensus," Nomura’s Sonal Varma says.

She adds that the quick succession of

She adds that the quick succession of