Bezos explained the core of his approach. First, the company will keep investing for long-term market leadership rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions. Second, the company will make bold rather than timid investment decisions. “Some of these will pay off, others will not," Bezos stressed. Profit was not even remotely on the radar of the maverick entrepreneur.

A little under two-and-a-half decades later in India, a clutch of loss-making tech startups are also taking the ‘Amazon route’ to listings, wanting investors to adopt a long-term view. “We have a history of net losses," declared One97 Communications, the parent company of digital payments platform Paytm, in its draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) filed on July 16.

The fintech major posted a net loss of Rs4,235.5 crore, Rs2,943.3 crore and Rs1,704 crore for FY19, FY20 and FY21 respectively. One97 Communications, which plans to raise Rs16,600 crore through its public issue, gave a peek into the future as well. “We may not be able to achieve and maintain profitability," the DRHP stated. The company, read the prospectus, expects to continue incurring net losses for the foreseeable future.

Loss-making online food delivery aggregator Zomato, whose IPO opened on July 14, too does not expect to turn the red its books to black in the immediate future.

“We expect our losses will continue given significant investments expected towards growing our business," the company stated in its DRHP, which shared the financials. Zomato posted a loss of Rs107 crore, Rs1,010 crore, Rs2,386 and Rs682 crore for FY18, FY19, FY20 and nine months of FY21, respectively. Interestingly, Zomato and Paytm are not alone in posting heavy losses. Most tech startups that are planning to go public over the next few months have a bleeding bottom line.

Welcome to the new world of listing in India where tech startups are unapologetic about losses, new-age entrepreneurs are bold about their long-term vision, and retail investors are betting on companies not on the basis of their track record, but on the basis of their promise of a rewarding future for their companies. Some of the IPO-bound startups include ecommerce platform Flipkart, logistics and supply chain services company Delhivery, beauty and fashion ecommerce platform Nykaa and insurance aggregator Policybazaar [for more, see box, ‘It’s Raining Startup IPOs in India].

![]()

IPOs by Indian tech companies, say analysts, not only offer moksha to the early set of investors, but also a chance to retail investors to own a piece of this ‘rewarding future’, if the startups deliver on their promises.

Take, for instance, the Zomato IPO, which was subscribed by little over 38 times. While retail investors bid 7.5 times for the loss-making company, institutional investors subscribed around 52 times. Zomato now is likely to be valued at Rs 64,365 crore, which is far higher than what even profitable restaurants and food brands command in the country. Take, for instance, Jubilant FoodWorks. At Friday’s closing (July 16), the master franchisee of Domino’s Pizza in India and other markets had a market cap of Rs 41,502 crore.

“The Zomato IPO is a trendsetter in the Indian startup ecosystem," says Anil Kumar, chief operating officer of homegrown consulting firm RedSeer. The listing sends three strong signals, he explains.

First, it tells venture capitalists, private equity investors and others that there is finally an exit route, and it is happening in India. Second, successful listing increases the confidence of those investors who so far shied away from investing in the Indian tech startup story.

Third, India could potentially become a global destination for big foreign investors. “Look what is happening in China," Kumar says. The State is clamping down on startups and the Chinese tech market is becoming dicey for investors. This year, he underlines, India not only got more dollar investment in internet companies than China, but the country also managed to outscore China in terms of unicorns [a startup valued at Rs100 crore].

The excitement around tech IPOs stems from the fact that these companies have grown over the last decade and a lot of funds have managed to exit with handsome returns. The retail investor now wants a pie. “These Indian companies have grown in maturity, with better unit economics and healthier business models," says Pankaj Naik, executive director and co-head, digital and technology at Avendus Capital.

One of the reasons why the metrics of these mature startups is looking good is due to the fact that customer acquisition cost has come down during the year, he explains.

“When these companies spend marketing dollars on acquiring customers, they are actually going after the consumer who is motivated to do a transaction," Naik says. “Three or four years ago, they were spending money on acquiring consumers who were probably window shopping, or not yet comfortable with digital transactions."

![]() For investors, a handy metric to judge these companies could be looking at the business moat and the growth that the user base can bring in. Does the company have a competitive edge in the space it caters to? Consumer and marketing metrics show how much it costs the company to acquire a user, retain them, and get them to use the service or product repeatedly, points out Nimesh Kampani, president at LetsVenture.

For investors, a handy metric to judge these companies could be looking at the business moat and the growth that the user base can bring in. Does the company have a competitive edge in the space it caters to? Consumer and marketing metrics show how much it costs the company to acquire a user, retain them, and get them to use the service or product repeatedly, points out Nimesh Kampani, president at LetsVenture.

The key metrics to track are long-term sustainable unit economics, repeat user rate, cost of customer acquisition, customer lifetime spend and return on ad-spends. “These metrics are important to identify if the company has charted a clear path to profitability in the future," underlines Kampani.

Back to the Amazon example in the US. The company posted its first full year of profit in 2003—$35million—six years after going public. The loss for the preceding year stood at $149 million. A decade later, however, it faced flak for its razor-thin profit margin.

“Amazon is a charitable organisation being run by elements of the investment community for the benefit of consumers," Slate columnist Matthew Yglesias commented in January 2013 after Amazon came out with its 2012 earnings report. Bezos did not agree with the assessment. “Take a long-term view, and the interests of customers and shareholders align," he said in his letter to shareholders.

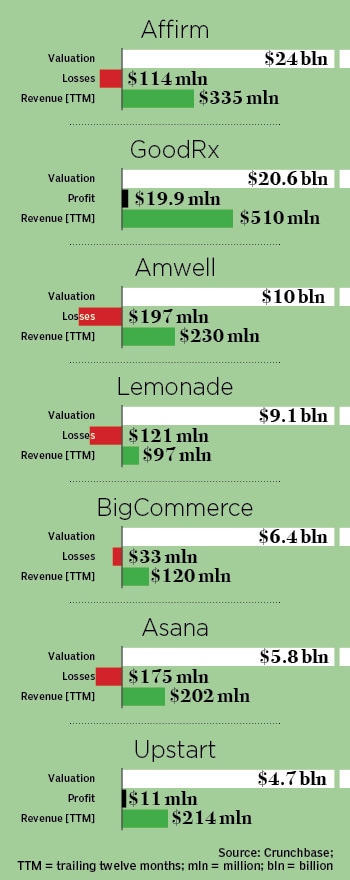

America’s love with loss-making tech companies remain unabated to this day. In February, Crunchbase looked at 12-month earnings for a sample of 12 venture-backed public companies that got listed in 2020. While three-fourths posted losses in excess of $100 million, companies with the highest revenue also posted some of the largest losses [See box ‘Report Card: Global Tech Companies Listed in 2020’)

Back in India, though regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) has allowed loss-making companies to get listed, it has a built-in mechanism to protect retail investors. Unlike in normal cases where profitable companies are allowed to offer 35 percent of the book to retail subscribers, loss-making companies can offer only 10 percent of its shares to retail investors during the listing. The rule essentially tries to protect retail investors from investing in companies which have not shown any road to profitability.

![]()

Zomato’s listing, though, might change the game as profit will take a back seat. “Other loss-making startups with strong fundamentals can opt for this route," says Ankur Bisen, senior vice president (retail & consumer products division), at Technopak. The IPO, he says, also creates a reference point in a country that is not used to listing of loss-making companies.

Though wooing people on the premise of a promising future is something that investors are used to in the US, in India, this just the beginning. Any comparison with Amazon, he sounds a word of caution, must keep in mind the fact that the US etailer morphed into a huge machinery with multiple revenue engines. Indian startups too must look at various ways to keep expanding the topline, and with an eye for profitability in the future. “End of the day, getting listed is just the beginning," he says. Markets duly reward the performers and punish the laggards.

Bezos, too, knows the market fundamentals. In his letter to shareholders in April 2013, he stated why only one thing matters performance. “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine," he said, quoting economist and investor Benjamin Graham. Amazon, he pointed out, is not euphoric with a rise in the stock price. “We aren’t 10 percent smarter when that happens (10 percent increase in stock price) and conversely aren’t 10 percent dumber when the stock goes the other way," he said. “We want to be weighed, and we’re always working to build a heavier company," Bezos underlined.

Indian tech companies—now making a beeline to get listed—must also keep a firm eye on the weighing machine of the company as well as the markets.

From Paytm to Zomato, loss-making ventures are getting listed by opting for scale over profit in the short-term

From Paytm to Zomato, loss-making ventures are getting listed by opting for scale over profit in the short-term

For investors, a handy metric to judge these companies could be looking at the business moat and the growth that the user base can bring in. Does the company have a competitive edge in the space it caters to? Consumer and marketing metrics show how much it costs the company to acquire a user, retain them, and get them to use the service or product repeatedly, points out Nimesh Kampani, president at

For investors, a handy metric to judge these companies could be looking at the business moat and the growth that the user base can bring in. Does the company have a competitive edge in the space it caters to? Consumer and marketing metrics show how much it costs the company to acquire a user, retain them, and get them to use the service or product repeatedly, points out Nimesh Kampani, president at