Laws of the Jungle: For this VC firm, it's about growing slow, lying low and bui

Jungle Ventures is fuelling dreams of founders who harbour pan-Asia aspirations and are not content with a dominant India play. Will its gambit pay off?

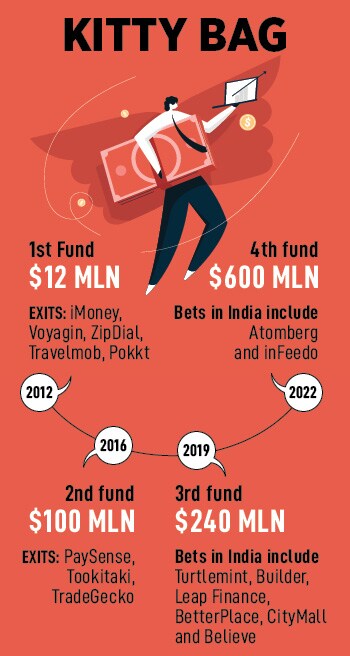

Bengaluru, 2016. The brief was clear. The potential investors were keen to meet the top five people working at a consumer tech startup, which was at the final stage of a sizeable funding. The pre-funding diligence was crucial for the largest and the oldest Singapore-based venture capital firm, which had rolled out its first fund of $12 million in 2012, and had backed early to growth-stage startups in India and Southeast Asia, and had counted mobile tech firm ZipDial as its maiden investment in India back in 2013. “We killed the regular process in 2015," recalls Amit Anand, founding partner at Jungle Ventures, alluding to the ritual of entrepreneurs pitching to the investment committees (ICs) of the VC fund as the penultimate step before bagging the funding. “It was a completely wrong process," reckons the VC, who had flown down to India along with his senior team to spend at least a day or so with the founders who had ticked all the boxes, and had to just clear one last hurdle before becoming part of the Jungle portfolio.

Anand explains the flaws in the ‘regular’ process. For years, explains the venture capitalist—who had once donned the mantle of a founder with his Singapore-based animation studio Ettamina in 2006—Anand and his team used to meet scores of brilliant founders. All of them had amazing pitches, most were brilliant storytellers, and everybody flaunted ambitious strategies to conquer the world. They knew how to woo investors during the IC meetings. The problem started when the promise and the vision didn’t match the execution.

There was one seminal learning: The success of the business doesn’t rest on the founder. “The success is on the team that the founder builds," says Anand, who had exposure to sales and business development during his stints at the Nasdaq-listed IT firm Progress Software, and Epiva and Tata Infotech before he took a plunge into the investment world. “We changed the IC process, and now we would go and meet the founders and their team," he says. “We want to see what they would order for lunch," smiles Anand. “We also see how they behave in the office."

Meanwhile, in 2015, Anand was about to witness a behaviour that only a privileged few could boast of. Ratan Tata joined Jungle Ventures as special advisor. “We got a chance to meet him multiple times," says Anand, who was intrigued by the way the legendary industrialist would behave during conversations. Every time the Jungle co-foudners would talk about startups, founders and the ecosystem, his eyes would lit up. “You could sense his excitement and his interest in the conversation," he recounts, adding that the meetings would end up with a piece of golden nugget from the former chairman of the Tata Group. In one of the quarterly meetings, Anand kept babbling about investments by companies like Tencent, Google, Alibaba, Facebook (now Meta), and the startups that were increasingly getting funded by the American and Chinese biggies. “Mr Tata stayed mum for two hours," he recounts. And then came the golden nugget. “I don"t know which startup is building to be here forever," he said, reckons Anand. The message was delivered. The Jungle co-founders started looking for founders who were building to last.

Meanwhile, in 2015, Anand was about to witness a behaviour that only a privileged few could boast of. Ratan Tata joined Jungle Ventures as special advisor. “We got a chance to meet him multiple times," says Anand, who was intrigued by the way the legendary industrialist would behave during conversations. Every time the Jungle co-foudners would talk about startups, founders and the ecosystem, his eyes would lit up. “You could sense his excitement and his interest in the conversation," he recounts, adding that the meetings would end up with a piece of golden nugget from the former chairman of the Tata Group. In one of the quarterly meetings, Anand kept babbling about investments by companies like Tencent, Google, Alibaba, Facebook (now Meta), and the startups that were increasingly getting funded by the American and Chinese biggies. “Mr Tata stayed mum for two hours," he recounts. And then came the golden nugget. “I don"t know which startup is building to be here forever," he said, reckons Anand. The message was delivered. The Jungle co-founders started looking for founders who were building to last.

Back in Bengaluru in 2016, Anand and his team reached the startup’s office that they were interested in funding. The co-founders had huddled the top five executives of their company into a room. No marks for guessing, each one had the best LinkedIn profile in terms of educational and professional experience. “This is the team you should meet," stressed one of the founders. “They are most articulate and they can explain to you the best," he underlined. Anand, though, was not impressed. His logic was interesting. The people who have seen the ride since day one, and have been through the ups and downs are the ones that must be among the top five. “If you want to know the organisation, you have to meet them as well," he says, underlining one of his top learnings from the investment world. “Execution eats strategy for lunch," he says.

The VC shares one more insight into the way Jungle operates. One must see if the founders, Anand underlines, stay in the room after the introduction. Historically, it has been seen that the founders who didn"t transition to become great CEOs were the people who stayed in the room after making the intros to their team. If you are staying back, Anand reckons, then you don’t trust your team. If a funder has invested in a business where the founder is not the right CEO, then one has made an investment error, he reckons. “And it"s the VC to blame here," says Anand, who learnt from his failure and journey. “I"m a failed entrepreneur who turned into an investor," he confesses. “I was a great founder, but a terrible CEO," he adds. His journey as an investor, Anand explains, is to help founders transition into world-class CEOs. “My failures are my teachings to my entrepreneurs," he says.

The VC shares one more insight into the way Jungle operates. One must see if the founders, Anand underlines, stay in the room after the introduction. Historically, it has been seen that the founders who didn"t transition to become great CEOs were the people who stayed in the room after making the intros to their team. If you are staying back, Anand reckons, then you don’t trust your team. If a funder has invested in a business where the founder is not the right CEO, then one has made an investment error, he reckons. “And it"s the VC to blame here," says Anand, who learnt from his failure and journey. “I"m a failed entrepreneur who turned into an investor," he confesses. “I was a great founder, but a terrible CEO," he adds. His journey as an investor, Anand explains, is to help founders transition into world-class CEOs. “My failures are my teachings to my entrepreneurs," he says.

At Jungle, there are only three rules to survive and thrive. First, one has to grow slow. The sector-agnostic VC fund, which has over $1 billion in AUM (asset under management) makes around 15-18 investments per fund. In terms of annual bets, it boils down to backing 6-7 ventures every year. What this set of concentrated portfolio means, explains Anand, is that it helps Jungle in making high-conviction bets. The founders end up getting more time, resources, and capital from the same fund. When Jungle closed the first fund of $12 million in 2012, it made under 20 investments from the fund. “Now we have a $600-million fund and we will still do under 20," he says.

Second rule is to lie low. It means staying grounded to pick up startups that might not have scale, but have margins. “If we don"t see margins, then we don’t invest in building scale," says Anand. This also means that if a startup is burning cash, but has an inherent margin in the business, Jungle would not think twice about backing it. “Even if it’s a gas guzzler, we are happy to invest," says Anand, explaining the reason behind backing CityMall. The grocery-focused social commerce startup fired around 15 percent of its staff in June this year, reportedly posted an operating revenue of Rs14.95 crore in FY21 and a loss of Rs10.4 crore, and is yet to file FY22 numbers. Anand is still bullish on the startup. CityMall, he maintains, has healthy margins in the business in Tier II, III, IV and V cities. “To build scale, they will probably need hundreds of millions of dollars, and we"ll continue to support them," he says, adding that high conviction in backing ventures has paid off in the past.

Second rule is to lie low. It means staying grounded to pick up startups that might not have scale, but have margins. “If we don"t see margins, then we don’t invest in building scale," says Anand. This also means that if a startup is burning cash, but has an inherent margin in the business, Jungle would not think twice about backing it. “Even if it’s a gas guzzler, we are happy to invest," says Anand, explaining the reason behind backing CityMall. The grocery-focused social commerce startup fired around 15 percent of its staff in June this year, reportedly posted an operating revenue of Rs14.95 crore in FY21 and a loss of Rs10.4 crore, and is yet to file FY22 numbers. Anand is still bullish on the startup. CityMall, he maintains, has healthy margins in the business in Tier II, III, IV and V cities. “To build scale, they will probably need hundreds of millions of dollars, and we"ll continue to support them," he says, adding that high conviction in backing ventures has paid off in the past.

Take, for instance, Livspace. The omnichannel home interior and renovation platform turned unicorn early this year when it raised $180 million in February. Led by KKR & Co, the Series-F round also saw participation from existing investors such as Ingka Group (Ikea) and Peugeot Investments, apart from Jungle Ventures. “Today, they have scale and dollars for acquisitions, but they always had the margin," says Anand, who also has unicorns Moglix and Kredivo in his portfolio.

“Margin before scale is crucial for us," he says. In their suite of three unicorns, Anand explains, Jungle’s portfolio lacks fluffy valuations. “We were never into that game," he says. Back in 2019, when Jungle was raising its third fund of $240 million, LPs (limited partners) wondered whether Jungle was into private equity or venture capital, alluding to lack of exaggerated valuation of any of its portfolio startups. “But look at the multiples. They are all venture capital returns," is how the VC defended the strategy.

The beginning, though, has to be small. “We have built Jungle to help startups grow" says Anand, explaining the philosophy behind the name of the fund. When you"re a new organism, you need an ecosystem in which you can survive and thrive. “Jungle is that ecosystem," he signs off.

First Published: Nov 21, 2022, 16:50

Subscribe Now