Mister India: Inside Xiaomi's transformation into a Made-in-India brand

Manu Jain has pulled out all stops to project the born-in-China Xiaomi as a made in India label, but is there a flipside to building the brand around an individual?

Manu Jain, the Global VP of Xiaomi and the Managing Director of Xiaomi India. Photo by: Nishant Ratnakar[br]

May 2020, BengaluruIt was a question based on perception. “Who do you think is the biggest monster in the ocean," the seven-year-old lobbed an innocuous query at Manu Jain on a placid Sunday afternoon. For the doting father, an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta, it was a no-brainer. “It’s a shark," the 38-year-old smirked. “Is it a whale?" he took another wild shot after a pause. The young kid, who started discovering the wild and aquatic life on the planet during the lockdown last year, was not impressed. “Wanna try again?" he asked. Jain appeared to be slightly lost.

The managing director of Xiaomi India was distracted. Jain’s mobile phone kept buzzing intermittently: WhatsApp messages continued to pop up on the bright screen and relentless email notifications choked the inbox. The country was under the first spell of lockdown, which had just entered the first week of May after a month of shutdown in April, and there was no respite yet. “April was zero for all," recalls the global vice president of Xiaomi, the biggest smartphone player in India. “Everybody performed equally well. All were No 1 in April," he smiles. Well, that seemed to be the perception.

The reality, though, remained that Xiaomi still had the crown. In the first quarter of last year—January-March—Xiaomi posted a 31 percent market share, a sequential rise of 3 percent and year-on-year jump of 1 percent, according to Counterpoint Research. The second and third in the pecking order—Vivo and Samsung—were at 17 percent and 16 percent, respectively. Though 2019 was a milestone year for Xiaomi—selling 100 million smartphones in five years since 2014—last April the reality was ‘zero’ business for all, including Xiaomi.

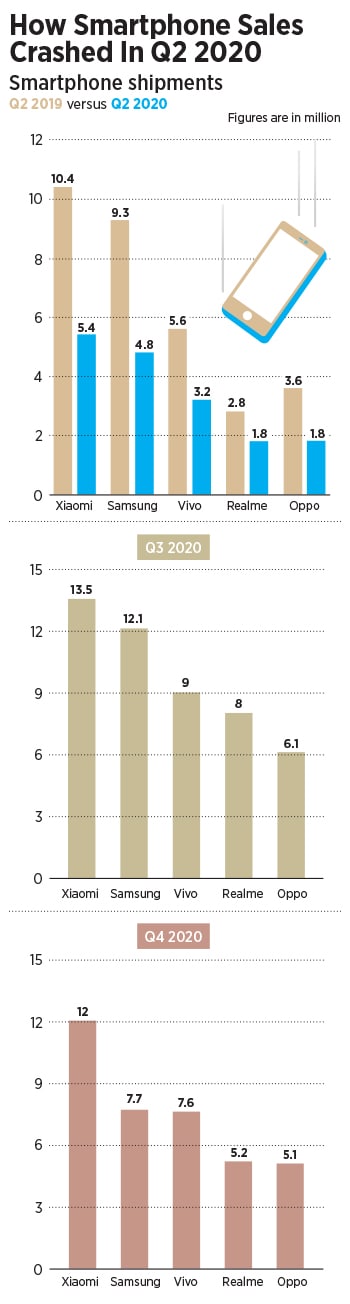

In the second quarter of 2020, the smartphone market dipped by 50.6 percent year-on-year to 18.2 million units, down from 36.8 million units a year ago, according to market tracker firm IDC. The top three in the pecking order were Xiaomi with a 29.4 percent share, Samsung with 26.3 percent, and Vivo with 17.5 percent.

“In May and June, we did a very small fraction of what we usually do," says Jain. If you look at IDC or Counterpoint numbers, you will see that the market was much smaller. “Second quarter was probably the toughest period from a business perspective," he adds. Xiaomi’s overall shipments volume fell by 48.7 percent year-on-year to 5.4 million units.

It seemed like business as usual during the beginning of this year. As the country got out of the lockdown mode, Xiaomi witnessed healthy demand driven by the growing need for devices per household and the need to upgrade existing gadgets.

Then came the second wave gate-crashing into the party. “Currently, with different cities going under a lockdown, we continue to assess the situation and impact that the second wave of Covid-19 will have on life and business," says Jain. The company, he adds, has been proactively working with its partners in hiring additional workforce to tide over short-term challenges such as absenteeism in case of localised lockdowns or restrictions. The experience of lockdown during the first wave last year, he feels, has made the company better prepared in managing supplies and expectations of consumers this time.

Analysts are cautiously optimistic about the second wave not being as severe as the first. “The April-June quarter is expected to have growth challenges under the weight of the second wave of infections," contends Navkendar Singh, research director at IDC. Though the high shipments from the first quarter should be able to suffice for the immediate demand, the impact might be less pronounced than last year, with factories being operational, limited restrictions on logistics and transportation and prevalence of state-level lockdowns instead of a nationwide lockdown.

The recovery this year, though, might not be as smooth as expected earlier. There is still uncertainty around the lasting impact of the second wave and a possible third wave over the next few months. Any rebound in consumer sentiments in the second half of this year will result in a single-digit growth annually. The degree of growth, though, will be restricted due to reduced discretionary spending, supply constraints, and anticipated price hikes in components in upcoming quarters, adds Singh.

For Jain, the past seven-odd years have proved to be a roller-coaster ride. Back in July 2014, as the country head of an obscure smartphone brand from China, which was making an audacious India debut with a flash sale of its flagship Mi 3 on ecommerce marketplace Flipkart, Jain had all the right to feel apprehensive. “What if very few turned up," wondered Jain, who had put some 10,000-odd units on sale. The fear was real. Few in the offline world had heard about Xiaomi seven years ago over 90 percent of smartphones were sold through brick-and-mortar stores. A few who did know didn’t have a great perception about a bunch of Chinese brands, which struggled with imagery of poor quality. At least, this is what the predecessors of Xiaomi had managed to build in India.

Six years later, in June, Jain was feeling the heat on multiple fronts. First, demand skyrocketed, but supply stayed scrappy. People scrambled for smartphones and laptops, as an online-only world became the new reality. “From a business perspective, we saw the highest possible demand and lowest possible supply during the second quarter of 2020," he recalls. Second, though eight factories across Haryana, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu started opening, workers remained apprehensive. The fear of contracting the disease was quite high, the business was still struggling, and the news of layoffs and furloughs across the country did no good in soothing the nerves of the jittery employees. “We decided to pay everybody, no matter what," Jain recounts. Over 50,000 workers—directly and indirectly employed—were not going to lose their jobs, he added. Thirdly, amidst the first wave of the pandemic, a strong clamour of ‘boycott Chinese goods’ started resonating across the country. India and China got embroiled in a bitter border dispute, which claimed lives on both sides. Emotions ran high, as nationalism became the guiding principle for the citizens, and the perception of Chinese brands in India was likely to take a huge hit.

Jain was on sticky ground. In terms of business, it was déjà vu. The same question that haunted him in 2014 revisited after six years: “How many would buy my brand." Social media, the biggest weapon of Xiaomi to make a dent in the Indian market with its large army of followers, was the new battleground. Jain, with a massive 465.6K followers on Twitter, started getting trolled.

Meanwhile, in Mumbai, around 990 km from Jain’s corporate headquarters in Bengaluru, Girish Rao had made up his mind. A kirana store owner who used to make some extra bucks by selling idols of Ganesha every year in the run-up to the Ganpati festival, Rao was consumed by patriotism. In June last year, India’s finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman wondered about the need for importing idols from China. “Why are even Ganesha idols imported from China," she reportedly asked. “Can’t we make a Ganesha idol from clay?" Rao saw enough merit, and logic, in Sitharaman’s argument. “I decided to buy idols made by Indians," he recalls.

In the national capital, the call for buying goods made by home-grown companies meant trouble for Ram Kumar. But for different reasons. Kumar, who runs a food truck in Rohini, southwest of Delhi, feared his business would go for a toss. His concern was genuine. Who would have bought food from ‘Ram Chinese’ corner? He had a point. In Kolkata, Xiaomi’s huge ‘Made in India’ banners outside Mi showrooms in June last year camouflaged the Chinese name. Could Kumar also have done a similar trick? He resisted the temptation. “I have been in the business of Chinese foods for over five years," he says. People, he underlines, love Chinese food. Kumar’s partner, Kunal, intrudes. “It’s not Chinese. It’s Indian Chinese."

Back in Bengaluru, Jain found himself in the midst of the Indian and Chinese problem. “It was tough," he recalls, alluding to the situation in June last year. “I would be lying if I say that I was not bothered." What made matters worse for Jain was a chain of sequential events: A lockdown in March, crashing of business in April, safety and concern of workers the next month, and then the flaring geopolitical tension in June. “I am responsible for 50,000 people and their families," underlines Jain. “I didn’t want any trouble for the Xiaomi India family."

There was trouble, though, for the smartphone maker. Market share dipped by a hefty 6 percent, from 29 percent in April-June last year to 23 percent in the subsequent quarter (July-Sept). Xiaomi now lost the crown to South Korean rival Samsung, after maintaining the lead for over two years. The perception fast gaining ground was that Xiaomi, being the biggest Chinese smartphone brand in India, was getting bruised in the geopolitical crossfire. The critics predicted doomsday to be around the corner for Chinese brands desi smartphone makers like Micromax—who at one point of time were cheap clones of the Chinese brands—whiffed a realistic chance of riding back on the wave of nationalism, and some even gave former Finnish monarch Nokia a realistic chance of coming back into the game.

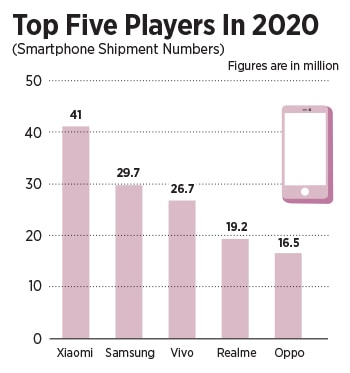

Cut to May 2021. Not only did Xiaomi come back strongly in the last quarter of 2020—with a 26 percent share—to reclaim the crown, over a year into the pandemic, but Jain has also managed to do something unthinkable: Stay No 1. In the first quarter of this year, Xiaomi has maintained a good 6 percent lead over Samsung. The third biggest player, Vivo, is behind by 10 percent.

Xiaomi, reckon smartphone analysts, has trumped rivals in its understanding of the needs of Indian consumers. “They know what Indians are looking for in terms of value, price, specs, features and channel presence," contends Singh of IDC. Xiaomi’s strong multi-channel play, which includes beefing up its offline presence, as well as a loyal Mi fan community, have also played their role in making the brand scale in India. That the local unit in the country is being run by Indians helped a lot in terms of connect, understanding and independent decision-making, Singh stresses.

Brand experts, though, point out the hidden and the most potent reason behind Xiaomi’s ability to navigate the love-hate relationship in India. “It never forgot who it is," says Ashita Aggarwal, a marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. Xiaomi, she adds, never ran away from its roots, and identity. Though the brand was born in China, it was painstakingly made in India over the last seven years. “Just like Indian Chinese food, Xiaomi’s story is more of being an Indian Chinese brand," she points out.

Back in Bengaluru last year, Jain too wanted to scream aloud his story. “I wanted to tell people that we are as Indian as it can be," he recalls. Even at the peak of the controversy, he lets on, it was crystal clear that the brand would not shy away from communicating with the users. “We knew who we are," he says. “It is true that we originated from China, and I"m not hiding this."

There was another reality, though, that Jain wanted people to know and appreciate. His tweet on June 20 last year nailed his feelings. “We are more Indian than anyone else," he tweeted, underlining five points in support of his Indian credentials. First, the R&D centre and product team is in India. Second, the phones and TVs are made in India. Third, the leadership of Xiaomi is Indian. Fourth, the company employs 50,000 people in India. And, last, it pays taxes in India and invests back in the country. The tweet ended with four hashtags: Xiaomi, India, Proud Indian and make in India.

In essence, Jain wanted to convey that Xiaomi is more of a global brand, a multinational company, which is building a local company in India. “I wanted to tell this story then, but it was not the right time because emotions ran high," he says, using a cricket analogy to explain how he handled the crisis last year. At times, a batsman has to duck some bouncers and wait for the right time. “We knew people were upset, but they were not upset with us," he adds. The brand was perceived to be honest, and had nothing to hide.

A brand, maverick entrepreneur Elon Musk once pointed out, is just a perception. “And perception will match reality over time. Sometimes it will be ahead, other times it will be behind," the founder of electric carmaker Tesla once reportedly pointed out. The brand, he reiterated, is simply a collective impression some have about a product.

In India, the collective impression of Xiaomi was shaped to a large extent by the way Jain handled the brand from the Day One. Celebrated adman KV Sridhar explains the nuances of how an Indian became the face of a Chinese brand. “What comes to your mind when you think of Samsung," he asks. One doesn’t even know, he lets on, who heads it in India. “All one can think about is a South Korean brand," says Sridhar, global chief creative officer at Nihilent Hypercollective. The answer won’t be different in terms of recall if one replaces Samsung with a Vivo, Oppo or any other Chinese brand or even for that matter brands from Japan. For all such brands, he explains, the nationality happens to be the de-facto face. “Xiaomi happens to be an exception," he says. Manu Jain, an Indian, has been the face of a Chinese brand from the beginning. “An Indian face, an Indian team, and Indian way of communication make Xiaomi an honorary Indian brand," he contends.

Back in March this year, Jain yet again underlined how he has handled Xiaomi in India. “Let us pay tribute to the great Indian fighters Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru," he tweeted on March 23. Hashtag with India and the national flag was towards the end of the tweet. “Jay Hind, bande mataram, inkalab jindabad" was how one of the followers replied.

Jain has transformed Mi, which originally meant ‘Mobile Internet’ (some even say ‘Mission Impossible’) to ‘Made in India’. Mi India, Redmi India and Poco India—the three sub-brands under Xiaomi India—had one thing in common: An Indian upbringing. The reality of a brand ‘Born in China’ has been masked by the perception of a brand ‘Made in India’.

Brand experts point towards another grim reality that Xiaomi must keep in mind. Any brand which is tied to and built around an individual or personality has a huge flip side as well. China, points out Harish Bijoor, is not a great country of origin to depend upon in the Indian context. So Manu Jain becomes the face. The idea being that the brand is a persona. “He has shielded anti-China sentiments so far," says Bijoor, who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. Where Xiaomi has to work, he points out, is in terms of brand imagery. There is no direct link between market share and imagery, Bijoor contends.

A brand such as Nokia, which is almost non-existent in India, still has a positive and high brand imagery. Xiaomi, he underlines, has a lot to do to reach that level.

Jain, for his part, asserts that the brand has been relentlessly doing its bit to become a darling of the masses. After all, people don’t buy a product if they don’t like a brand. “I can only focus on my inputs. I don’t know the results," he says.

The results, it seems, have started to come, both in terms of consistently maintaining the market share as well as appreciation from the users. On April 22, Jain tweeted that Xiaomi India is procuring over 1,000 oxygen concentrators to help the country tide over oxygen requirement in its fight against Covid. Nishant Jain, one of the followers, retweeted. “Great initiative," he replied to the tweet. “Sometimes, I personally believe Xiaomi is an Indian company that work for people of India and doing great work."

A year later in Bengaluru, Jain now has the answer to the question asked by his son. “Plastic is the biggest monster," his son replies. The reality, at times, depends on how something is perceived.

First Published: May 18, 2021, 14:04

Subscribe Now