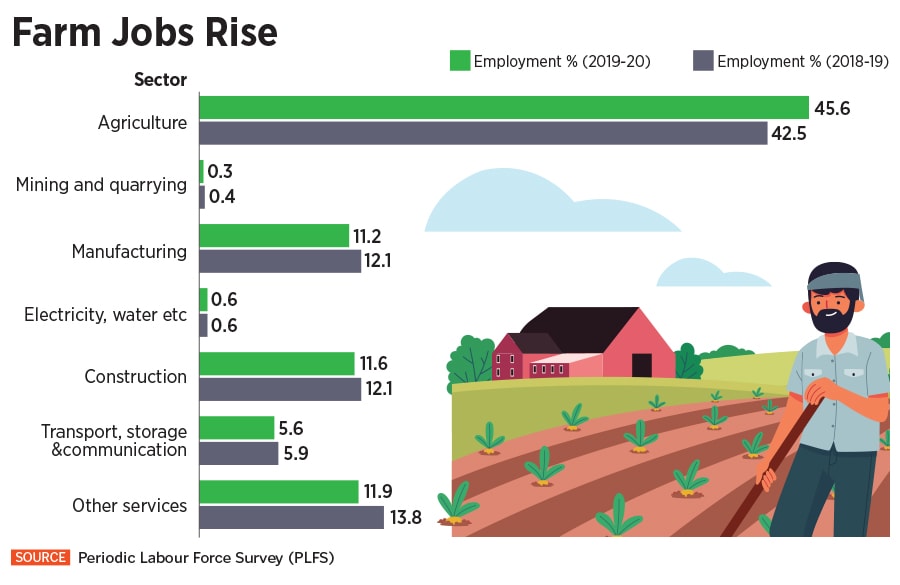

The latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for the 2019-20 period corroborates this alarming trend. It states that jobs in agriculture rose to 45.6 percent from 42.5 percent in the previous year. However, employment across manufacturing and construction declined during the same period (see chart).

Mahesh Vyas, MD and CEO, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), explains why this is a troubling trend and how it could be a sign of hidden unemployment.

“Employment in the non-agricultural sectors has stagnated and even declined. As a result, people have moved back to the farms. Now, this is very peculiar to India. In most countries when jobs shrink in the industrial parts of the country it leads to high unemployment. In India people just move back to the farms. And when people move back to the farms it is not that they produce more agricultural output. It is the productivity of labour that falls, because most of the people moving back to the farms are actually engaged in disguised unemployment," Vyas says.

Pranjul Bhandari, chief India economist, HSBC, says this grim reality is partly the fallout of the disruption caused by the pandemic. She expects some jobs to be restored once the economy returns to normalcy. But she points out that many jobs may no longer be available due to the closure of small-scale manufacturing units, for example. “At this time, it is difficult to say which jobs fall in the former or latter category," she says.

![]()

Stress in the job market

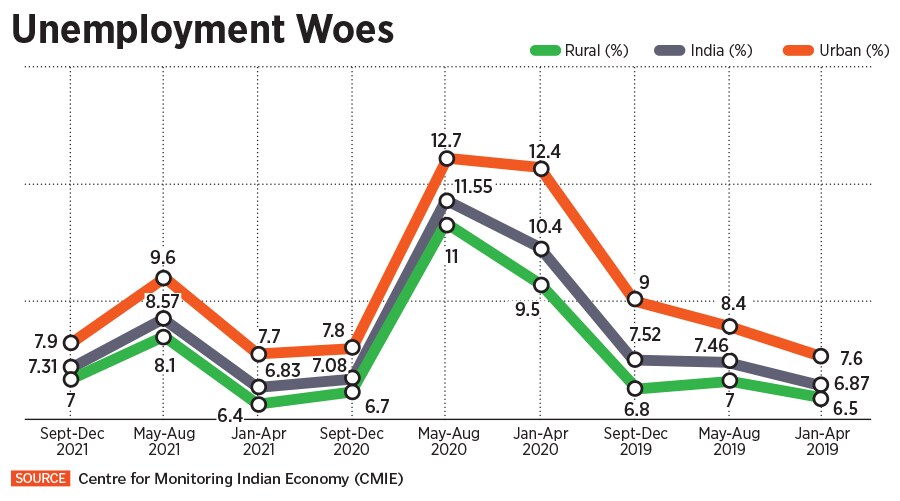

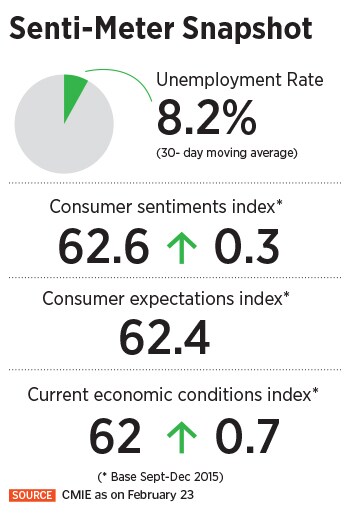

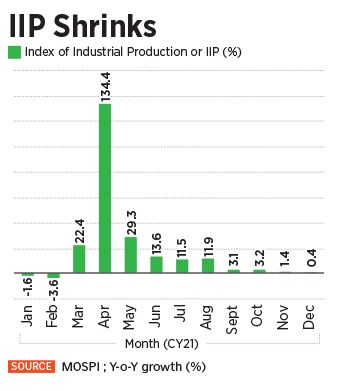

Tepid consumption, a lull in economic activity (see chart), and the lack of an urban safety net for migrant labourers has worsened the situation and high unemployment has been a key concern (see chart). Nalini Gulati, country economist at International Growth Centre (IGC), told Forbes India in January, “The share of urban jobs is falling, and within that, the share of better-paid, salaried jobs is also falling."

According to a Motilal Oswal research report dated December 9, due to migration from urban to rural areas, around 9.3 million workers were employed under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) each month in FY21. This increased by 20 percent to 11.2 million workers per month between April and November last year. “Migrant workers, thus, are yet to feel confident enough to move back to urban centres," says the report.

![]()

The high demand for the government’s flagship scheme under MGNREGA serves as a good indicator of the underlying stress in the job market. Labour economist KR Shyam Sundar, professor at XLRI Jamshedpur cautions, “The rural economy has always been the shock-absorber in India, but this is an unsustainable model of employment generation."

Vyas is not hopeful of a quick turnaround in the situation due to the lack of substantial investments.

“[With] the pace of investments in manufacturing and the fact that most manufacturing and services sectors are increasingly moving towards automation, the possibility of significant labour movement back into non-farm sectors looks remote to me now because none of the factors that help in doing so are in play," Vyas says.

![]()

Economist Mitali Nikore, founder of Nikore Associates, a youth-led economics research and policy think tank, says that while the government has already prioritised self-reliance as an agenda to create jobs and has announced production-linked incentives to push manufacturing, there is need to complement it with “employment-linked incentives, because these can complement increasing production, by incentivising incremental job creation".

While economists were hoping that MGNREGA will get a boost in the Budget presented by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman on February 1, the Centre slashed allocations by about 25 percent to Rs73,000 crore--from a revised estimate of Rs 98,000 crore for 2021-22 and the actual expenditure of Rs 1,11,170 crore in 2020-21.

Given the disruption at the bottom of the pyramid, Bhandari says she would have preferred the government to have continued its social welfare schemes for some more time. However, she adds, “My sense is that eventually they will not spend all of the outlay on capex because there tend to be a lot of implementation issues on the ground, and some of it may be used for social welfare schemes, and so they will end up spending more on NREGA than they have budgeted."

![]() The big capex bet

The big capex bet

While the government has cut its spending on social welfare schemes, it has increased its capital expenditure by a whopping 35 percent to build infrastructure. It hopes this strategy will crowd in private investments, create jobs, boost consumption, and spur growth. Will this bet pay off?

Vyas says he is not convinced with the government’s narrative that high public capex will draw in private sector investments. Based on estimates and analysis, he explains the capex to be undertaken by the central government directly is approximately 10.5 percent in nominal terms.

“The budget numbers don"t give me the confidence that it is going to spur investments and therefore create jobs," Vyas adds.

Bhandari explains a 35 percent rise in capex roughly translates into an increase of 0.4 percent of GDP. “Generally speaking, in any given year, the government can do an additional 0.2 percent capex. But they have changed their strategy. The central government is tying hands with the state government and I think this will make the implementation better and faster," she adds.

However, Bhandari is sceptical if this can fast-track growth or generate jobs. She asserts that public capex constitutes only 20 percent of the total capex in the economy. Private investments—constituting nearly 80 percent of total capex—play a crucial role in expanding the capacity of the economy and creating employment. However, business confidence remains muted, and the outlook for private investments is lacklustre.

![]()

“The government can do all the capex it wants to do but eventually the aim is to crowd in private capex. But is private capex coming? I can"t say that with certainty," Bhandari says.

![]() While corporate balance sheets have improved, there is a lot of uncertainty around government policy and economic growth. For example, commodity prices are increasing, there is geopolitical tension, central banks are changing their policy stance, etc. In turn, it is hard to forecast how growth will pan out given the volatility. And this is what is coming in the way of private investments and hence job creation, observes Bhandari.

While corporate balance sheets have improved, there is a lot of uncertainty around government policy and economic growth. For example, commodity prices are increasing, there is geopolitical tension, central banks are changing their policy stance, etc. In turn, it is hard to forecast how growth will pan out given the volatility. And this is what is coming in the way of private investments and hence job creation, observes Bhandari.

“The rich have got richer, while those at the bottom of the pyramid have got poorer-now how the two come together, which will overpower the other, these things are hard to predict with certainty, and in an environment of uncertainty private capex does not tend to flourish," Bhandari says.

Sundar says that capex takes time to kick in and the government needs to focus on getting money into the pockets of people with measures that will have a more immediate impact. “There is a lot of scope for creating these jobs in the urban sector, like the municipal works through urban local bodies, like repair of roads, street lighting etc.," he says. He adds that this will increase income levels of families, and lead to an increase in aggregate demand, which in turn will lead to investment.

![]()

“My back of the envelope calculation is that a 1 percent decline in unemployment in the urban areas will lead to at least a 1.5 percent decline in rural unemployment, with 0.5 percent being a magnifying effect," says Sundar, stressing that the labour market will reach some sort of equilibrium only when unemployment levels decrease and plateau to about five or six percent. “There is a desperation in the labour market, and it is time the government addresses the painful employment issue."

Tepid consumption, a lull in economic activity (see chart), and the lack of an urban safety net for migrant labourers has worsened the situation and high unemployment has been a key concern

Tepid consumption, a lull in economic activity (see chart), and the lack of an urban safety net for migrant labourers has worsened the situation and high unemployment has been a key concern

The big capex bet

The big capex bet

While corporate balance sheets have improved, there is a lot of uncertainty around government policy and economic growth. For example, commodity prices are increasing, there is geopolitical tension, central banks are changing their policy stance, etc. In turn, it is hard to forecast how growth will pan out given the volatility. And this is what is coming in the way of private investments and hence job creation, observes Bhandari.

While corporate balance sheets have improved, there is a lot of uncertainty around government policy and economic growth. For example, commodity prices are increasing, there is geopolitical tension, central banks are changing their policy stance, etc. In turn, it is hard to forecast how growth will pan out given the volatility. And this is what is coming in the way of private investments and hence job creation, observes Bhandari.