Budget 2022 and the inequality in necessities

Why it may be time to stop looking for instant gratification—like investor and taxpayer sops—from budgetary proposals. Just don't tell that to the pandemic-hit jobless and children in rural schools

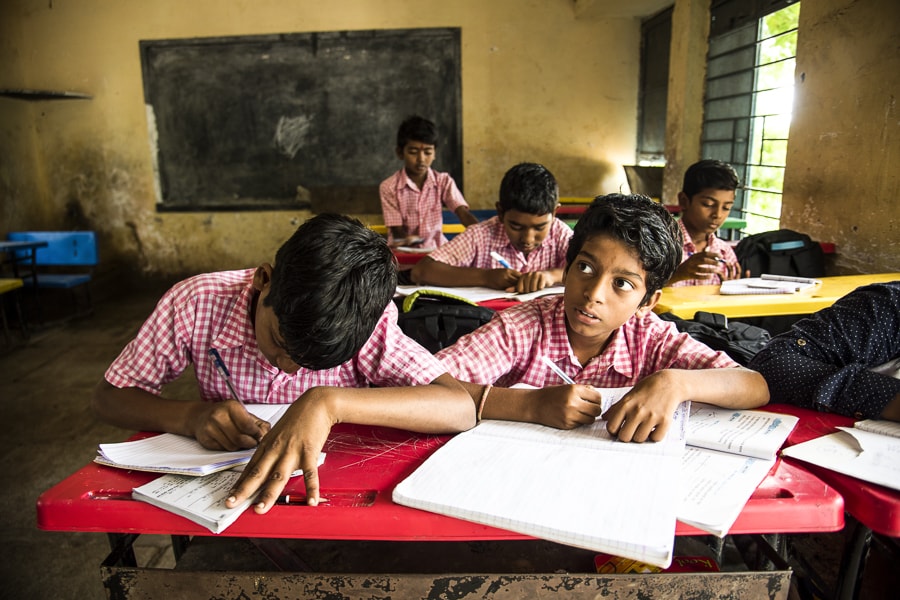

Additional support for public schools to improve the teacher-pupil ratio, classroom space and teaching/learning materials will be a challenge for the government

Additional support for public schools to improve the teacher-pupil ratio, classroom space and teaching/learning materials will be a challenge for the government

Image: Shutterstock

When, minutes into her speech, Finance Minister (FM) Nirmala Sitharaman declared that Budget 2022 would lay the building blocks for the next 25 years of the Indian economy, it held promise of a vision document that took both long-term objectives and short-term challenges into account. Sure enough, there was plenty of the former, with high-technology and digital being the fuel for inclusive development, energy transition and infrastructure creation, from roads, railways, airports and ports to mass transport, waterways and logistics. Such massive capital expenditure—public and private—will over time create employment, which in turn will have more citizens spending and contributing to the growth of a robust economy.

A grandiose blueprint for an India at 100 from an India at 75 brought expectations of a ‘dream budget’—an exaltation first created when India was at 50, in 1997. If Manmohan Singh’s 1991 budget ensured that India embarked on the road to economic reform and liberalisation, the 1997 edition ensured continuity at a time when the path ahead seemed headed towards a dead end. Then Finance Minister P Chidambaram pulled out some heavy artillery to ensure that the pace of reform would be swifter and bolder: The maximum marginal income tax rate for individuals was lowered, rates for domestic companies were cut, customs duties were slashed, and excise duty structures were streamlined—all pretty radical steps in the 90s (and would be considered progressive even today).

Budgets on their own don’t determine long-term economic success, but it wouldn’t be incorrect to say that the 1997 edition did its bit to boost tax collections, spur economic growth and set the stock market indices free in the decade that followed—till the 2008 global financial crisis ended the party.

What does Chidambaram’s Dream Budget have in common with Budget 2022, and the last few of Sitharaman? Both aspire to create long-term transformational change. For instance, in 2020, Sitharaman stressed on the theme of “Ease of Living, Aspirational India, Economic Development and a Caring Society". These entailed farmer welfare, infrastructure creation and climate change, among other sub-themes. A year later, the buzzwords were in a similar vein: Nation first, doubling farmer’s income, strong infrastructure, inclusive development, among others.

Strip away fancy words, and it’s difficult to accuse the government and the FM of inconsistency in vision. As she noted in Tuesday’s speech, the stress is on the sunrise opportunities for a modern tomorrow: Artificial intelligence, drones, space, genomics, clean mobility et al.

The problem with long-term blueprints is two-fold: One, public attention spans are short, with a tendency to see only fragments than a bigger picture that includes pieces from the past and, two, that having over the decades made it a Woodstock-like event of the financial markets, investors and taxpayers are accustomed to looking for instant and annual gratification from budgetary proposals. But none of that was coming: Not at least major sops for taxpayers and investors.

On the flip side, some sections were relieved that were no negatives, while others have made it a ritual to scrounge for positives and convert proposals with a potential for long-term transformation into short-term triggers for sentiment-boosting. The urgent need for substantial hikes in healthcare and education allocations and the burning problems of job and demand creation can safely be subsumed into the successes of the vaccination campaign and the proposals for supplementary education for the pandemic-hit.

The Economic Survey released on Monday acknowledged that the “pandemic has had a significant impact on the education system, affecting lakhs of schools and colleges across India". As comprehensive official data on the pandemic effect on enrolments and dropouts is available only till 2019-20 with the Ministry of Education, the Survey relied on smaller surveys by citizen-led non-government agencies for clues. One such is the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER 2021). The picture is a mixed one: Enrolment of 15-16 years improved and the number of children in this age group not enrolled declined. That’s the good news. The not-so good news is in rural India: As per the ASER (Rural) report, children between 6 and 14 not enrolled increased from 2.5 percent in 2018 to 4.6 percent in 2021.

Another disturbing trend is that children in rural areas moved out of private schools to government schools across age groups. Possible reasons for this shift: Shutdown of low-cost private schools, financial distress of parents, free facilities in government schools and disproportionately high fees in private schools.

The challenge then for the government? As the Survey pointed out, additional support for public schools to improve the teacher-pupil ratio, classroom space and teaching/learning materials. Now, all this of course can’t happen in a year, or even three, but try telling this to a school student who the pandemic has set back a couple of years and is ill-equipped with skills to see her through the next few of her life, never mind 25 years.

First Published: Feb 01, 2022, 16:33

Subscribe Now