When founders turn funders

Through the trend of founders becoming angel investors, helping new startups raise the precious early dollar, is not new--the pace and the ballooning ticket size is astonishing

Abhishek Goyal, co-founder of Tracxn, says if angels do not make money, they will not be able to invest further. His involvement, though, doesn’t end with a fat cheque[br]Abhishek Goyal got addicted during his Accel years. Working as an associate at the marquee venture capital (VC) firm for three years—from 2008 to 2010—the IIT-Kanpur grad got a taste of the highs of investment early in his career. In 2009, Accel led the first ever investment in Flipkart, when Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal were running the business out of their apartment. “I helped them spot Flipkart,” recalls Goyal, co-founder of Tracxn, a market intelligence platform for tracking startups and companies.

Abhishek Goyal, co-founder of Tracxn, says if angels do not make money, they will not be able to invest further. His involvement, though, doesn’t end with a fat cheque[br]Abhishek Goyal got addicted during his Accel years. Working as an associate at the marquee venture capital (VC) firm for three years—from 2008 to 2010—the IIT-Kanpur grad got a taste of the highs of investment early in his career. In 2009, Accel led the first ever investment in Flipkart, when Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal were running the business out of their apartment. “I helped them spot Flipkart,” recalls Goyal, co-founder of Tracxn, a market intelligence platform for tracking startups and companies.

By the time Goyal left Accel, he was hooked to the venture world, though in a different avatar of an angel investor. In 2011, a year after he quit Accel and turned entrepreneur by starting an online fashion and beauty venture UrbanTouch, Goyal made his first angel investment in Delhivery, a logistics startup. The trigger to invest was simple: The nascent startup had ticked both the boxes that mattered to Goyal: Pedigree of the founders and the blue ocean (new market) into which they had plunged.

Goyal liked Sahil Barua, one of the co-founders. “Sahil had a good gravity in his character,” he recalls. The startup, he lets on, was working in the ecommerce logistics space, and Goyal—already running a vertical ecommerce startup—sensed Delhivery might be the next big thing. “That made me invest,” he says, declining to share the amount invested.

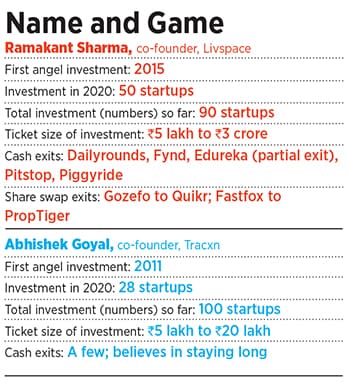

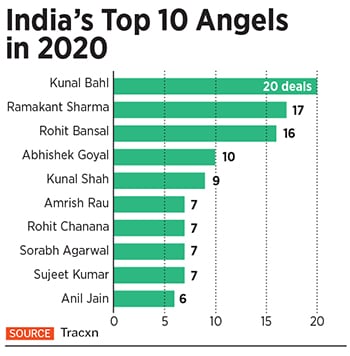

By the end of 2020, Goyal ended up investing in 28 startups as an angel. Since 2011, he has invested in over 100, with the ticket sizes between ₹5 lakh and ₹20 lakh. The journey has been financially and emotionally rewarding. “Angel investing comes with a satisfaction of helping smart founders in their early days,” he says.Goyal is not the only founder who has turned funder. Consider Ramakant Sharma, co-founder of Livspace, an interior design marketplace, who has invested amounts ranging from ₹5 lakh to ₹3 crore in a bunch of ventures. Last year, Sharma was the second biggest angel in India, with 50 investments. Interestingly, most of the names on the top 10 list of angels are entrepreneurs who have donned the hat of investor (see box). Though the trend is not new, the pace at which founders are turning angel—and the ballooning of the ticket size—is astonishing.

For Sharma, the trigger to invest is simple: Help startups raise the precious early dollar. His involvement, though, doesn’t end with a fat cheque. “I contribute through brainstorming, and connect them with my network,” he says. The intention of the entrepreneur is clear: To get a bang for his buck. “If angels do not make money, they will not be able to invest further,” he says.As entrepreneurs mushroom in the third-largest startup ecosystem of the world—in 2020, India produced a record 12 unicorns—the country would not only see institutional angel investing gathering steam but also hordes of founders turning angels.

“Founders-turned-investors understand the pain areas of startups,” says Vikram Gupta, founder and managing partner of IvyCap Ventures, a homegrown VC firm making early bets in startups. The founders, Gupta explains, have gone through similar challenges while starting up their own businesses. Entrepreneurs with prior knowledge and expertise about the nuances of business operations not only provide the financial support but also the necessary knowledge, contacts and entrepreneurial promptness to undertake decisions intuitively. “This adds credibility to the ventures,” he says, adding that an entrepreneur-angel is likely to bring more experience on board. There is another positive. Such angels come up with new ideas and accelerate innovation in the startup ecosystem.

A decade back, the trend largely emerged out of the need to invest in the startups of fellow alumni or within one’s network. An IITian would end up investing in a startup started by an alumnus. The same was the case with IIM alumni. It was a mom-and-pop industry, where an angel was more of a Santa. Cheques were cut, and no return was expected. Gradually, angel investing got structured, and institutional bodies jumped into the fray. “When IvyCap Ventures started this trend years ago, there was hardly any other investment company doing the same,” claims Gupta, who started the fund in 2011. Looking at the success of this model, he adds, other investors jumped on the bandwagon.  Sweta Rau has been investing as angel through her company White Ventures since 2017[br]For Sweta Rau, who first turned angel in 2014, such form of investment is all about creating the foundation for a successful business. A former entrepreneur—she started an ecommerce venture, Glamdebox, to discover lifestyle luxury products in 2012—Rau has been investing as angel through her company White Ventures since 2017. For her, the fundamentals of investing haven’t changed: Familiarity breeds money. As you do more deals, she explains, and meet more founders, you get to learn more businesses and tend to develop mental models. “This helps in the selection criteria, and you tend to apply stricter metrics,” she says. Rau has invested in over 30 startups, including direct-to-consumer tea brand Vahdam.

Sweta Rau has been investing as angel through her company White Ventures since 2017[br]For Sweta Rau, who first turned angel in 2014, such form of investment is all about creating the foundation for a successful business. A former entrepreneur—she started an ecommerce venture, Glamdebox, to discover lifestyle luxury products in 2012—Rau has been investing as angel through her company White Ventures since 2017. For her, the fundamentals of investing haven’t changed: Familiarity breeds money. As you do more deals, she explains, and meet more founders, you get to learn more businesses and tend to develop mental models. “This helps in the selection criteria, and you tend to apply stricter metrics,” she says. Rau has invested in over 30 startups, including direct-to-consumer tea brand Vahdam.

For Sharma of Livspace, there is only one criterion to invest: Connect with the founders. When Sharma met the founders of PharmEasy to understand the scalability of their ecommerce model, he ended up investing twice in the venture. Later he wrote the first cheque for Toothsi, a dental tech startup, and a company started by the wife of one of the PharmEasy founders. Sharma then again invested in HobSpace, an edtech startup, of the wife of another founder of PharmEasy. There are more connections-based investments. One of Edureka’s founders was Sharma’s flatmate years ago. After they met again at a party in 2015, Sharma ended up investing in his business. A founder of Zolostays was Sharma’s classmate from ISB. “I ended up investing here, and again in a Series C round,” he says. Livspace’s Ramakant Sharma was India’s second biggest angel—with 50 investments—in 2020[br]Ask him if he has made money, and the reply comes as quick as drawing the first cheque: “My investment is not charity. It’s a belief-driven participation in the growth startup ecosystem.” Angels, he points out, too need to make money. “If they don’t, how will they invest?”

Livspace’s Ramakant Sharma was India’s second biggest angel—with 50 investments—in 2020[br]Ask him if he has made money, and the reply comes as quick as drawing the first cheque: “My investment is not charity. It’s a belief-driven participation in the growth startup ecosystem.” Angels, he points out, too need to make money. “If they don’t, how will they invest?” There is a flip side to such investment as well. Gupta of IvyCap Ventures explains. At times, such entrepreneurs start investing after raising Series B, C or D rounds in their own companies. “There could be potential conflict in such scenarios,” he says. Such investments, Gupta underlines, may take away the focus of such entrepreneurs from their business. Second, the entrepreneur-turned-investor might have a strategic interest in the startups that may limit the independence and scale of the company. There are examples where entrepreneurs, after having raised large amounts of capital in their own company, started investing heavily as angels and eventually their own company shuttered. There are also cases where startups that raised money from such investors compromise on their own independence and scale. Then there is an ‘emotional’ angle to contend with. An entrepreneur-turned-investor may get emotionally attached with their investment and influence the vision of the investee founder, changing their course of business. “It’s not easy donning such hats,” he says.

There is a flip side to such investment as well. Gupta of IvyCap Ventures explains. At times, such entrepreneurs start investing after raising Series B, C or D rounds in their own companies. “There could be potential conflict in such scenarios,” he says. Such investments, Gupta underlines, may take away the focus of such entrepreneurs from their business. Second, the entrepreneur-turned-investor might have a strategic interest in the startups that may limit the independence and scale of the company. There are examples where entrepreneurs, after having raised large amounts of capital in their own company, started investing heavily as angels and eventually their own company shuttered. There are also cases where startups that raised money from such investors compromise on their own independence and scale. Then there is an ‘emotional’ angle to contend with. An entrepreneur-turned-investor may get emotionally attached with their investment and influence the vision of the investee founder, changing their course of business. “It’s not easy donning such hats,” he says.

Turning angel might be easy, but staying one may be another ball game.

First Published: Jan 20, 2021, 11:29

Subscribe Now