“Operations on this floor run 24x7 since they are completely automated. Our machines can manufacture 40,000 units per day," says the floor operations manager. Since it was an automated unit, there were fewer employees, with most focusing on quality checks. The rest of the assembly took place on the other floors, each with close to 2,000 people.

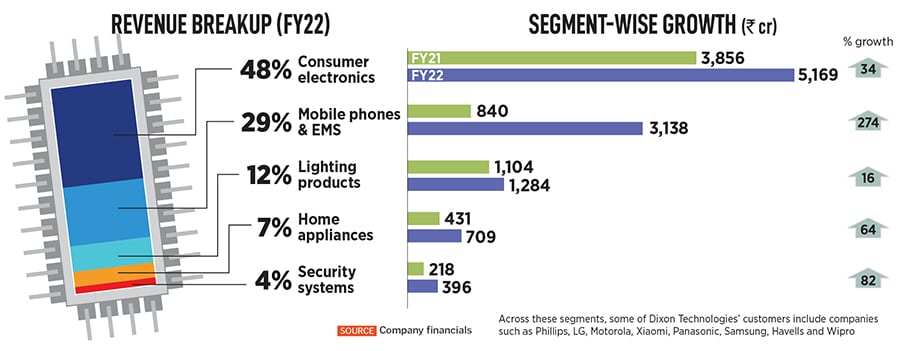

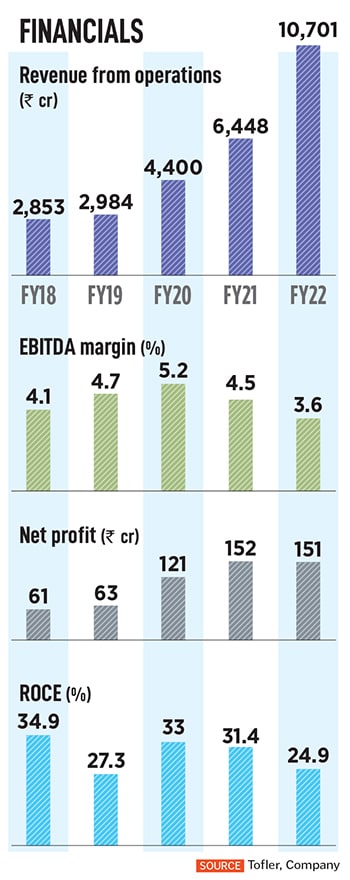

This was one of the 17 manufacturing units across the country—from Noida in Uttar Pradesh to Chittoor in Andhra Pradesh—that one of India’s largest electronics manufacturing services (EMS) companies, Dixon Technologies, runs. It has expanded from CRT televisions (TV) to consumer electronics, lighting, home appliances, mobiles and a lot more, growing into a ₹10,700-crore powerhouse that is valued at ₹20,000 crore on the stock market.

All this began with one factory that co-founder Sunil Vachani set up in 1993, to manufacture CRT: A 10,000 sq ft rented plot in Noida, a few machines, 15 employees and ₹15 lakh that he borrowed from his father, Sundar Vachani.

In the early 1990s, after completing his Associates in Business Administration from American College, London, Vachani returned to India. He could have joined the family business, but he says, “I wanted to do something of my own, that was my passion." In 1989-90, he set up a factory to make cordless telephones, but it didn’t take off because of some missteps. Thereafter, he started training at his father’s TV manufacturing company, Weston, in the components department.

After a year-and-a-half, he mustered the courage to tell his father that he wanted to set up his own venture—manufacturing electronics. “At that time, the concept of manufacturing for other people was alien everybody believed that manufacturing is sacred, it has to be in-house and not outsourced. So, rightly, my father was a little apprehensive," recounts Vachani. The then-23-year-old had noticed a similar trend in a few global markets, and was certain it would come to India, soon enough. Eventually, his father agreed. But he asked “his blue-eyed boy", Atul Lall—who had worked at Weston for many years—to mentor Vachani.

![]() Atul Lall, co-founder and vice chairman, Dixon TechnologiesImage: Madhu Kapparath

Atul Lall, co-founder and vice chairman, Dixon TechnologiesImage: Madhu Kapparath

Lall had joined Weston in 1986, and looked after some of the component divisions and its international business. “I worked closely with Sundar Vachani. I was very young and he mentored me, which helped in shaping my career," he says. Weston did a lot of business in the erstwhile USSR, and when it collapsed, the company suffered immensely.

Soon after, Vachani started Dixon in 1993, and Lall joined him. It was only after a year that they first bagged an order from Lucky-Goldstar—now LG Electronics—which, in those days, only had a representative office. It was looking for a subcontractor to manufacture a few thousand TVs for exports. “We were one of the companies who sent in a quote for the order and were so desperate for business that we quoted a ridiculous fee of $1.5 per television," says Vachani.

It was a great learning experience, dealing with tough negotiations. Vachani credits Lucky-Goldstar for trusting new players with no prior experience. “I do think my late father’s legacy helped. People in the electronics business knew him and that’s what helped us get started," he adds. “I remember someone telling me, that I was too young to be a managing director. So I’d be lying if I told you that I had a five-year or 10-year plan. The idea was just to jump in, and see where it goes."

When Lucky-Goldstar moved to India, Dixon was on-boarded to manufacture TVs for the domestic market. After Lucky-Goldstar, Dixon bagged clients like Phillips for consumer durables, DVDs, audio and VCRs, and SEGA for video games consoles. Today, the company is the largest EMS player in India, with over 60 customers, including Phillips, Xiaomi, Samsung and Godrej.

![]()

Early days

Unlike a lot of startups today, Dixon Technologies made money from the first quarter. In the first year, it made a profit of ₹3 lakh, making a few thousand TV sets. The secret, says Lall, “is that we’ve been conservative with our capital allocation. We are in the business of outsourcing, which means you have to be frugal and cost conscious, and capital efficiency has to be of the highest order". This belief has been at the core of Dixon’s operations. In FY22, its revenue from operations is ₹10,700 crore and net profits ₹151 crore. “Everyone who reports to Atul, even engineers or heads of departments… he’s turned them into chartered accountants. Under his leadership, we’ve never lost money, except one year when the exchange rate of INR-USD turned against us and we were not completely hedged," says Vachani.

Lall and Vachani have had a great working relationship—with Lall focusing on numbers and Vachani looking at strategy, vision and government relationships. “In the last two to three years, we’ve started having different opinions about a lot of issues, which to me is a healthy sign. After having heated arguments, we always come to an agreement," adds Vachani.

But it was not easy, especially in the early days. Vachani recalls going to meet senior bureaucrats in the early 2000s to help create favourable policies for electronics manufacturing. They would tell him, “India’s future does not lie in electronics hardware, it’s software that’s our strength and that’s what you should be working on." Apart from convincing people that India would be the next electronics manufacturing hub, Vachani and Lall faced issues raising funds too. After knocking on many doors, one bank offered a loan against secured exports.

![]()

Hedging the risks

For the first eight or nine years, the company was focussed on one product—CRT televisions. “We were quite naive, practically running operations ourselves and didn’t think too much about the bigger picture. Then certain shocks came around 1997, when the export business closed. We realised this was a risky strategy, and tough to scale," recalls Lall. By then, they had a few clients such as LG, Sony and Phillips, so business carried on. It expanded to other categories like VCRs and telephones, but the majority of its revenue continued to come from TV. “We needed to expand our core—which wasn’t TV it was electronics manufacturing," he adds.

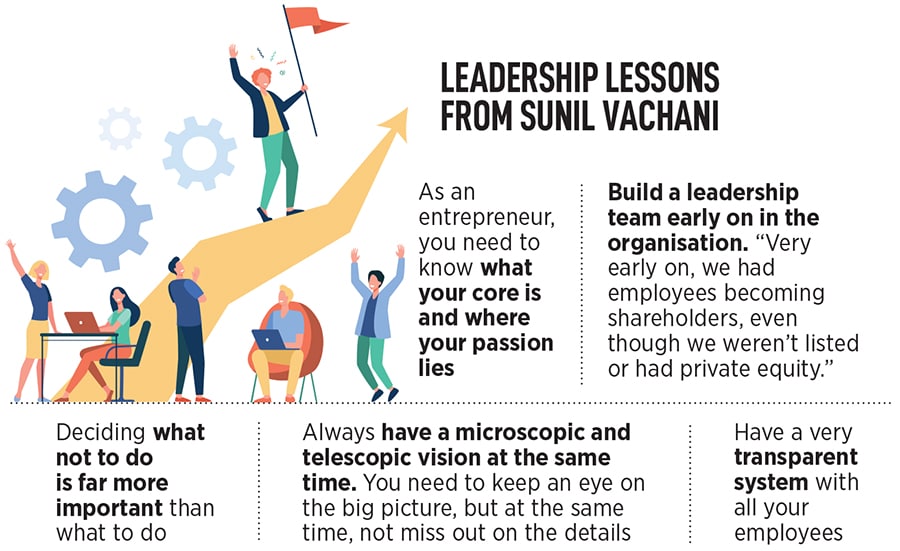

In the early 2000s, Dixon launched its own brand, only to realise that it was not part of its DNA. “They say that sometimes the decisions of what not to do are far more important than what to do. Running a consumer-facing brand was not something we were passionate about," says Vachani. After two-and-a-half-years, they realised its core was electronics manufacturing as a service and not a brand. “This was a turning point for us. Things changed dramatically after that... we found our core. Things started falling into place," says Vachani.

![]()

There are many EMS players who started off in the electronics manufacturing space, and set up a brand. Vachani and Lall are clear, “It is cast in stone—till we are a part of this company, we are not going to compete with our customers, ever."

In 2006, Dixon got an order from the Tamil Nadu government for 2.5 million CRT TVs under the state government’s free CRT TV scheme, which needed Dixon to scale up 10x. Banks were willing to fund them, but the duo wanted capital for the long term and decided to raise private equity.

Motilal Oswal saw an opportunity for growth in the electronics manufacturing segment in India, and came on board around May 2008. Vishal Tulsyan, CEO and managing director of Motilal Oswal Private Equity, says, “When we invested, their dependency on a few products and customers was very high. They needed to expand their product and customer base." Tulsyan and team helped Dixon’s core team realise the huge opportunity in India’s EMS segment. “We told them that in the manufacturing space you have to be the lowest cost producer at all times and asked them to focus on return on capital employed [ROCE], working capital and backward integration," adds Tulsyan. Motilal Oswal invested in Dixon when it’s valuation was less than ₹150 crore today it is almost ₹20,000 crore. In 2008, Dixon entered the lighting products segment by manufacturing CFL products, followed by washing machines for Godrej.

![]() In September 2017, it went for a public listing, one of the very few companies in the sector to IPO. The big trigger was to provide an exit to Motilal Oswal. When Dixon got listed, the turnover was around ₹2,000 crore in the last five years it has grown by 5x. “I think it was the the most subscribed IPOs in the history of electronics manufacturing in India," claims Vachani. The split-adjusted listing price was ₹352, which has since increased by over 10x, to ₹3,546, at the time of writing. Even now, in FY22, the company’s net debt-equity ratio is 0.1.

In September 2017, it went for a public listing, one of the very few companies in the sector to IPO. The big trigger was to provide an exit to Motilal Oswal. When Dixon got listed, the turnover was around ₹2,000 crore in the last five years it has grown by 5x. “I think it was the the most subscribed IPOs in the history of electronics manufacturing in India," claims Vachani. The split-adjusted listing price was ₹352, which has since increased by over 10x, to ₹3,546, at the time of writing. Even now, in FY22, the company’s net debt-equity ratio is 0.1.

After the stock’s phenomenal performance, Lall says, “We realised that more brands are going to focus on brand building and distribution, and designing only higher-end products. But designing and manufacturing of mass products is going to be through outsourcing this was the way forward."

The brand’s strength, Vachani feels is, “its agility, flexibility, frugal cost structure, sharp customer focus, innovation, scale, ability to stay ahead of the curve and a great team". Dixon has long-standing relationships with its customers. The relationship with Phillips goes back to 1994, and Dixon does more than 90 percent of certain categories in their consumer-end lighting products. Similarly, with Panasonic, it started nine years ago, with 5,000 TVs per month, but now Dixon does 100 percent of their TVs, washing machines and a large percent of their lighting.

Manish Sharma, president and CEO of Panasonic India and South Asia, feels, “What stood out when it came to Dixon was a professional organisation run by professionals, where the involvement and role of the promoters was limited only to strategy, governance and compliance. In any organisation, whether an MNC or promoter-driven, it is important to practise collective wisdom to fuel innovation or empower your people."

Lall credits Vachani for trusting his people. In 2022, Vachani was a debutant on the Forbes World’s Billionaires List, with a net worth of $1.1 billion. Apart from his humility and yearning for knowledge acquisition, he says, “Sunil has immense trust in his people. Dixon has been run through consensus building and not through dictat."

Global hub

The National Policy on Electronics 2019 has set a target for electronics production in 2025-26 at $300 billion, making India a global hub for electronics manufacturing. There are three opportunities: The domestic market penetration for electronics is extremely low most large companies looking to move operations out of China are considering India or Vietnam and a huge demographic dividend—with a large young population. “India has the potential to create huge employment opportunities," reckons Vachani.

![]() He feels a lot of these are covered in the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, which was announced in 2020 to encourage domestic manufacturing, across sectors, including mobile and electric components. “The PLI scheme can be a real game changer, if executed well and incentives are disbursed on time. It has the potential to transform the sector," says Vachani. So far, Dixon is part of five PLI schemes—mobiles, IT hardware, telecom, LED lighting components and air-conditioning components. The production for mobiles and IT hardware has begun. “Dixon has been aggressive in terms of having partnerships with multiple brands. The PLI scheme has benefited them and they are aggressively expanding their capacities and showing their capabilities to multiple brands," says Prachir Singh, senior research analyst at Counterpoint Research.

He feels a lot of these are covered in the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, which was announced in 2020 to encourage domestic manufacturing, across sectors, including mobile and electric components. “The PLI scheme can be a real game changer, if executed well and incentives are disbursed on time. It has the potential to transform the sector," says Vachani. So far, Dixon is part of five PLI schemes—mobiles, IT hardware, telecom, LED lighting components and air-conditioning components. The production for mobiles and IT hardware has begun. “Dixon has been aggressive in terms of having partnerships with multiple brands. The PLI scheme has benefited them and they are aggressively expanding their capacities and showing their capabilities to multiple brands," says Prachir Singh, senior research analyst at Counterpoint Research.

According to Vachani, the PLI scheme’s intention was to create large scale for companies to address global markets. It also gave a much-needed push to their mobile phone category. Though the segment only accounts for 29 percent of Dixon’s FY22 revenue, it has grown by almost 274 percent—from ₹839.76 crore in FY21 to ₹3,138.25 crore in FY22. Dixon is the second-largest mobile phone manufacturer in India. Vachani claims there is an opportunity for $100 billion (₹7,833,42 crore) in exports and ₹400,000 crore in the domestic market for this segment. “PLI was supposed to create a component ecosystem, which has partly happened in the mobile phones segment. A lot of parts are now being manufactured here, but a lot more needs to be done," he adds.

One element that is lacking in the Indian electronics manufacturing industry is the electronics component manufacturing segment. Vachani says, “In China, the bulk of component manufacturing is done by SMEs. This is where, as an industry, a lot needs to be done to ensure that SMEs invest in this sector. While there is a huge demand, not too many companies have invested in this segment." Some other areas where India needs to improve are poor infrastructure, high cost of logistics and transportation, and cost of power, since supply isn’t fully uninterrupted.

![]() At the first basement of Dixon Technologies’ Noida facility, 40,000 units can be manufactured dailyImage: Madhu Kapparath

At the first basement of Dixon Technologies’ Noida facility, 40,000 units can be manufactured dailyImage: Madhu Kapparath

The road ahead

In the last 29 years, the mindset of entrepreneurs in the EMS industry has changed. “About 10 to 12 years ago, there was a lack of optimism. I’m glad that not only entrepreneurs, but also stakeholders are realising that this is a sunrise sector," reckons Vachani. Lall believes the company will grow at a CAGR of 30 percent in five years: “The industry is at an inflection point, and undoubtedly we are in a lead position."

Dixon’s next phase of growth has only begun. With electronics manufacturing at its core, product diversification will continue growing. Before entering any new segment, they look at certain factors, such as scalability in the domestic and global markets, scope for backward integration, potential to get into design manufacturing... and there is a lot of outsourcing if in the category.

They have a few joint ventures in the works: One with Bharti Airtel for telecom hardware manufacturing another with Japan-based Rexxam for manufacturing printed circuit boards for air conditioners with CP Plus for security systems and the latest one with boAt to manufacture wireless audio products and smartwatches. “All of these new segments check all the boxes," adds Vachani. Apart from wearables and hearables, Dixon will also start manufacturing refrigerators from the first quarter, next year.

![]()

Going forward, Dixon hopes to focus on design-led manufacturing, expand deeper into existing client portfolios and on backward integration of key components. So far it hasn’t acquired any companies, but Vachani says, “When it comes to designing, we don’t want to be re-discovering the wheel in some segments to try and play catch-up with a company that has gone far ahead. So we would be looking at acquiring companies in that space." Dixon is looking to invest in research and development, processes and systems that are in tune with customer requirements and build layers of leadership across the organisation. The company would like to look at segments like electric vehicles components, medical electronics, defence and a lot more. “I don’t see these opportunities bottoming out for a very long time. But, at the same time, you don’t want to spread yourself too thin, not just in terms of financial resources but also bandwidth of the team," adds Vachani, who believes he is a paranoid entrepreneur and extremely risk averse. “I keep thinking, if we don’t change with times, we might just be disrupted."

As opposed to 29 years ago, Vachani has a clear vision: “I want Dixon to be one of the top five global EMS players and to be the most respected brand in the country and the world. Every time someone thinks of outsourcing for electronics, they should think of Dixon."

In September 2017, it went for a public listing, one of the very few companies in the sector to IPO. The big trigger was to provide an exit to Motilal Oswal. When Dixon got listed, the turnover was around ₹2,000 crore in the last five years it has grown by 5x. “I think it was the the most subscribed IPOs in the history of electronics manufacturing in India," claims Vachani. The split-adjusted listing price was ₹352, which has since increased by over 10x, to ₹3,546, at the time of writing. Even now, in FY22, the company’s net debt-equity ratio is 0.1.

In September 2017, it went for a public listing, one of the very few companies in the sector to IPO. The big trigger was to provide an exit to Motilal Oswal. When Dixon got listed, the turnover was around ₹2,000 crore in the last five years it has grown by 5x. “I think it was the the most subscribed IPOs in the history of electronics manufacturing in India," claims Vachani. The split-adjusted listing price was ₹352, which has since increased by over 10x, to ₹3,546, at the time of writing. Even now, in FY22, the company’s net debt-equity ratio is 0.1. He feels a lot of these are covered in the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, which was announced in 2020 to encourage domestic manufacturing, across sectors, including mobile and electric components. “The PLI scheme can be a real game changer, if executed well and incentives are disbursed on time. It has the potential to transform the sector," says Vachani. So far, Dixon is part of five PLI schemes—mobiles, IT hardware, telecom, LED lighting components and air-conditioning components. The production for mobiles and IT hardware has begun. “Dixon has been aggressive in terms of having partnerships with multiple brands. The PLI scheme has benefited them and they are aggressively expanding their capacities and showing their capabilities to multiple brands," says Prachir Singh, senior research analyst at Counterpoint Research.

He feels a lot of these are covered in the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, which was announced in 2020 to encourage domestic manufacturing, across sectors, including mobile and electric components. “The PLI scheme can be a real game changer, if executed well and incentives are disbursed on time. It has the potential to transform the sector," says Vachani. So far, Dixon is part of five PLI schemes—mobiles, IT hardware, telecom, LED lighting components and air-conditioning components. The production for mobiles and IT hardware has begun. “Dixon has been aggressive in terms of having partnerships with multiple brands. The PLI scheme has benefited them and they are aggressively expanding their capacities and showing their capabilities to multiple brands," says Prachir Singh, senior research analyst at Counterpoint Research.