Capri Global's Rajesh Sharma wants to tap into India's fintech revolution. Here'

How Rajesh Sharma rebuilt his empire and found his way to the Billionaires list

Rajesh Sharma has much to thank the city of Mumbai for. Especially, when it comes to making him a billionaire.

After all, it’s the country’s financial capital that sheltered him as a 20-something graduate, when he left his nondescript hometown of Mukundgarh in Rajasthan to pursue a career in chartered accountancy. It was also the city that showed him that pedigree was inconsequential, and what mattered was fortitude and perseverance.

“When you are in a city like Bombay (Mumbai) you can aspire for anything," Sharma says. “People look at what you can do, not what background you come from or who you are. That is the beauty of this city." Sharma moved to the city in 1989 and has since made it his home. In the process, he built a financial services firm, was arrested for an alleged bribes-for-loans scam before being discharged by the court, rebuilt his business into a notable Non-Banking Finance Company (NBFC), mopped up sporting franchises from kho kho to cricket, and this year, joined the coveted Forbes billionaires’ club.

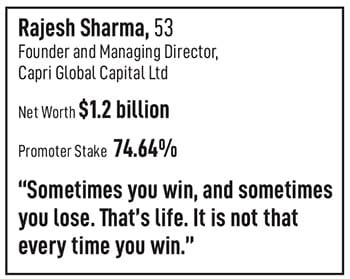

With a net worth of $1.1 billion, Sharma is the 2405th richest man in the world, according to the Forbes World’s Billionaires List 2023, the bulk of which he gets from a majority stake in the non-banking finance company, Capri Global Capital. Capri Global has a market capitalisation of ₹12,268 crore and offers home loans, construction loans as well as customised business loans for medium and small-scale enterprises.

“It doesn’t matter whether you have a wealth of ₹50 crore or ₹3,000 crore or ₹10,000 crore," Sharma tells Forbes India in a video interview. “I don’t think that changes anything. Irrespective of how much money you have, if you can get to a stage where you are free to decide what you want to do and especially those things that satisfy you, that is what matters."

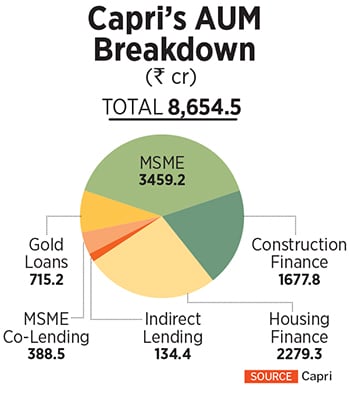

Sharma’s Capri Global is a dominant financial services player in the western regions of the country, especially Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Delhi NCR, where it has tapped heavily into the MSME lending space, in addition to home loans, over the past few years. The company claims to have over 600 branches across the country, and last year also forayed into the lucrative gold loan business.

Sharma’s Capri Global is a dominant financial services player in the western regions of the country, especially Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Delhi NCR, where it has tapped heavily into the MSME lending space, in addition to home loans, over the past few years. The company claims to have over 600 branches across the country, and last year also forayed into the lucrative gold loan business.

Capri, which began operations in its current form in 2011, is now targeting to open 1,500 gold loan branches over the next five years in Tier 3 and 4 cities to target the unorganised sector and build up a gold loan book size of ₹8,000 crore on the back of growing demand for credit, especially in rural India. Already, its strong focus on MSMEs has meant the company has financed nearly 35,000 enterprises across 11 states of the country, while also helping some 26,000 families in building affordable homes through its housing finance arm.

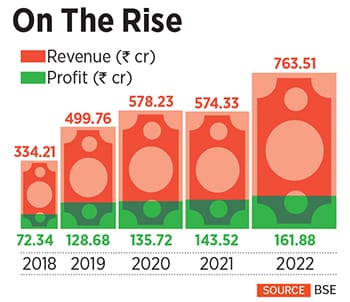

As of February, Capri has over ₹8,650 crore of Assets Under Management (AUM) with over 7,000 employees across 15 states in India. Its gold loan business has taken the market by storm, and, in just one year, built up 500 branches for gold loans across seven states in India. The gold loan business now accounts for nearly 10 percent of the AUM, in just seven months. Last year, the company’s revenues stood at ₹763 crore, while profits stood at ₹161.88 crore.

Sharma grew up in Mukundgarh, a small town in the Jhunjhunu district of Rajasthan, where his father worked as a telecom engineer with the government of India.

After graduating from Sharada Sadan College in Mukundgarh, Sharma made the long journey to Mumbai to study chartered accountancy, as was a common practice among young graduates in Rajasthan, widely known for their accounting and financial skills. In Mumbai, Sharma stayed at the Rajasthan Vidyarthi Griha, a hostel built in 1958 for aspiring chartered accountancy students from Rajasthan. “I am always grateful for the hostel and Mumbai for that opportunity," Sharma says. “I met so many students, and helped become part of a large, chartered accountant network."

In 1996, after working for a few years, Sharma set up his own professional services firm in Mumbai. “I started my own practice in financial services, where we used to help companies raise short-term capital," Sharma says. “Then we started investment banking practices and, till 2010, we were doing that."

In 1996, after working for a few years, Sharma set up his own professional services firm in Mumbai. “I started my own practice in financial services, where we used to help companies raise short-term capital," Sharma says. “Then we started investment banking practices and, till 2010, we were doing that."

That company, Money Matters soon grew into one of the fastest-growing investment banks in India, boasting a clientele that included the Adani Group, Tata Group, and Aditya Birla Group, and helped with loan syndication, debt placement, financial restructuring, and debt settlement.

In 2013, Money Matters changed its name to Capri Global under an agreement with Capri Capital Partners LLC, a US Securities and Exchange Commission-registered real estate investment adviser.

A year before that, the company raised ₹440 crore in equity capital and began its construction finance lending business. Sharma says Capri Capital never had any stake in the Indian arm and Money Matters only changed the name under the agreement with the global partner.

“We stuck to our core competencies," Sharma says. “Which was debt funding. And we started building retail lending. That was followed by recruiting people and opening branches." By 2013, the company expanded its business into MSME lending. “We identified the opportunity that banks do not lend in the informal self-employed, non-professional segment," Sharma says. “So there was an opportunity to start lending, and since we had an NBFC licence and capital, we ventured out."

“We stuck to our core competencies," Sharma says. “Which was debt funding. And we started building retail lending. That was followed by recruiting people and opening branches." By 2013, the company expanded its business into MSME lending. “We identified the opportunity that banks do not lend in the informal self-employed, non-professional segment," Sharma says. “So there was an opportunity to start lending, and since we had an NBFC licence and capital, we ventured out."

By 2017, the company also received a licence to launch a housing finance business and its branch count expanded to 66 with over ₹1,000 crore in AUM. Today, Capri’s loan book comprises five lending verticals—MSME loans, housing loans, construction finance loans, loans to other NBFCs, and loans against gold. Of this, MSME loans account for 40 percent of the AUM. The company is also a corporate selling agent for third-party new car loans, working with banks such as Union Bank of India, Bank of Baroda, and HDFC Bank among others.

“The asset quality risks are mitigated to some extent given that the entire portfolio is secured in nature," CareEdge ratings said in a report about Capri last year. “The MSME loan book is secured in nature with 65 percent in the form of self-occupied residential properties and 30 percent being commercial properties. The balance book is secured by way of industrial property. For the construction finance portfolio, nearly 85 percent of the portfolio is under principal moratorium as on March 31, 2022. However, low ticket size and prepayments in CF (Construction Finance) book (58 percent of the CF book under moratorium has already started prepayments) provides comfort."

Now, as India’s fintech revolution gets under way, the wily Sharma is also waiting to unleash new products to tap into the booming opportunity. “In the future, we might enter digital lending," adds Sharma. “We are evaluating that product and maybe in the next six months, we should be able to start something." India’s digital lending market is expected to be worth $350 billion in 2023, up from $270 billion in 2022, according to a study by credit reporting company Experian. Digital lending is also expected to surpass traditional lending, on the back of unsecured loans by 2030, according to Experian.

That’s why Sharma is optimistic about his plans. “India will grow, and our entire ecosystem is in place," says Sharma. “If you look at finance available to businesses like MSMEs, there’s a huge credit gap and, I think, in the next 10 years, we will help people grow their business. Our population is still underpenetrated in various aspects."

For now, Sharma is expecting Capri Global’s AUM to cross ₹30,000 crore in the next five years, and in the process enhance profits significantly, while taking the company’s total branches to some 1,500 across the country. For now, however, he wants to retain Capri’s focus in its core regional markets of western and central India for the next two years, before it looks at expanding business in other regions.

Along the way, Sharma is also mindful about converting his non-deposit taking NBFC into a small finance bank, the first step towards a universal banking licence. “At some point in time, we would like to convert this into a small finance bank or a universal bank depending on what kind of permissions when we get," Sharma says. The Reserve Bank of India last approved a consortium of Centrum Broking and BharatPe as a small finance bank in 2021. Among others, small finance banks in the country include the likes of AU Small Finance Bank, led by billionaire Sanjay Agarwal, Ujjivan Small Finance Bank, led by Ittira Davis, and Equitas Small Finance Bank, led by PN Vasudevan.

If he manages to do that, it won’t be Sharma’s first tryst with banking. In 2019, Sharma acquired a 4.99 percent stake in the now-defunct Laxmi Vilas Bank, which was eventually merged with Singapore-based DBS upon the instruction of the country’s central banker. “We lost that money," Sharma says. “It turned out to be a bad investment. Sometimes you win, and sometimes you lose. That’s life."

That’s perhaps a philosophy that has come to Sharma from his love of sports. Capri Global currently owns teams across varied sports such as kho kho, kabaadi, and cricket, particularly women’s cricket. And he reiterates that the foray into sports isn’t to promote the Capri brand. “I thought we must promote homegrown sports, and my idea was to contribute in some small way," Sharma says. “We have a large country, large population, and we still struggle in sports. That’s I want to promote sports."

Today, at 53, Capri takes up much of Sharma’s time, with very little time to unwind, barring occasional visits to stadiums during matches. “I believe that one should do what you enjoy doing," Sharma says. “If you do that, you will remain involved. That’s why I don’t get tired, and I don’t need to unwind."

So where does Capri go from here? “It’s very simple," Sharma says. “I want to make every vertical profitable, improve processes, and eventually convert into banking."

First Published: Apr 26, 2023, 13:12

Subscribe Now