Hyderabad: From sleepy town to fertile ground

The Telangana government's proactive measures focussed on building ecosystems is transforming Hyderabad into a hub for technology startups that could one day rival Bengaluru

Chaitanya Peddi, co-founder of Darwinbox

Chaitanya Peddi, co-founder of Darwinbox

Image: P Anil Kumar for Forbes India[br]Chaitanya Peddi, Jayant Paleti and Rohit Chennamaneni co-founded Darwinbox in 2015 in Hyderabad, a time when much of the startup action was in Bengaluru or Delhi. Only the previous year, the decade-long political movement for an independent identity for the Telangana region had ended with its creation as India’s 29th state, with Hyderabad as its capital.

Today, Darwinbox is thriving. Its employee life-cycle management software automates human resources processes for more than 200 mid- to large-sized companies, and collectively touches over 400,000 staff across these customers.

“In hindsight, we have never regretted starting up in Hyderabad, it was a good choice,” says Peddi. Revenue for 2018-19 rose 300 percent from the previous year, although Peddi didn’t provide specific numbers. He expects to “continue to maintain the momentum this year”.

Though the trio, who collectively bring experiences from EY, McKinsey and Google, was already working in Hyderabad and that made the city a natural choice, things have only become better over the last five years, given there was political strife in the past. Soon after it was formed, Telangana state’s new government turned its attention to attracting investor attention, especially in high-technology. A startup innovation policy was also put in place.

“One of the most talked about features in the policy is the assurance the government provides a home-grown startup by being its first customer,” Jayesh Ranjan, secretary for IT in the state government, told Forbes India in an emailed statement. More than two dozen products or solutions from startups have been rolled out in different government agencies in the last three years, Ranjan says.

Telangana’s government has also invested in creating high-quality physical infrastructure, of which T-Hub, an incubator and co-working space, inaugurated in November 2015, is best known. The government has also created other spaces such as the IMAGE incubator, the WE Hub, aimed at women entrepreneurs, and T Works for hardware engineering.

T-Hub was built within the campus of the Indian Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad (IIITH), but a larger facility, T-Hub Phase-2—built at a cost of ₹300 crore, and expected to be the world’s largest such facility—will be open for business by the end of this year. Private investment in physical infrastructure is growing too, with companies such as WeWork and 91Springboard starting co-working facilities in the city.

“Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai were the main south Indian cities that competed heavily with one another for IT/ITeS businesses,” says Vijaya Kumar Ivaturi, co-founder and CTO of Crayon Data, an AI and big data analytics company. An active startup ecosystem mentor and investor today, Ivaturi built wireless networks and mobile business units in Hyderabad in the late 2000s as the BU head of wireless business for Wipro. He was also an important technology leader for Wipro to create and grow embedded systems business with local defence and space establishments in Hyderabad in the early ’90s.

“The political uncertainty in undivided AP due to the demand for a separate Telangana state did concern many of the MNC customers as well as investors in tech ecosystems,” he says.

That and the corporate scams in IT and other sectors such as cooperative banks and pharmaceuticals aggravated the situation further, and many prospective customers and investors chose Bengaluru or Chennai instead. With the formation of Telangana, the political and policy stability factors improved. And “the sharp focus of the local government to regain the lost ground and leverage the existing infrastructure with government incentives to attract new businesses helped the state grow very well in recent years,” Ivaturi adds.

*****

When T-Hub started, there were no more than 500 startups in the city, but today there are some 4,000—tech and non-tech put together. The state’s proactive work, which also includes building an ecosystem for startups, is something experts point to as unique to Telangana and Hyderabad. “In the last four years, we have seen a lot of progress in the startup ecosystem here,” says Peddi at Darwinbox.The “knowledge ecosystem” in the city is improving, comprising other startups, mentors, early-stage investors, academic institutions, and industry partnerships. T-Hub has established close links with other institutions and corporate businesses. Chief Executive Ravi Narayan—a former Microsoft veteran—expects the hub to anchor an “innovation ecosystem” in Hyderabad in the coming years. “We are working to close the gap between academic research and startup innovation. We are hoping to see startups engage with the research centres for talent and to build out their technologies. And for the research centres, the startups present an opportunity to commercialise the work done in their labs,” says Narayan.

At the Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, part of IIITH, professor Ramesh Loganathan, COO of the centre, has ready examples of such efforts. “We have started to seed startups ourselves and build products at a product lab that is about a year old now,” says Loganathan. In the latter case, “against a curated market opportunity, we build the first version of the product ourselves.” Subsequently, the products are spun off as startups by identifying and working with entrepreneurs willing to commercialise the products.

Two such products are almost ready to be spun off. The first is a badminton analytics solution, where a computer watches a game and—using machine learning—provides insights similar to those a coach might have. “Star Sports got to know of this, and they came to talk to us, and they used the solution integrating it with its live feed in the PBL (Premier Badminton League) finals [in January],” says Loganathan. “Next year they want to use more of it, in the whole commentary and the narrative of the game.”

The second product is a document bot solution. Feed it a document and it automatically sets up a bot that will bring up information from any part of the document. A bank is in talks to use this technology to create thousands of FAQs for its staff. The bot can then bring up specific information that one asks for from the FAQs.

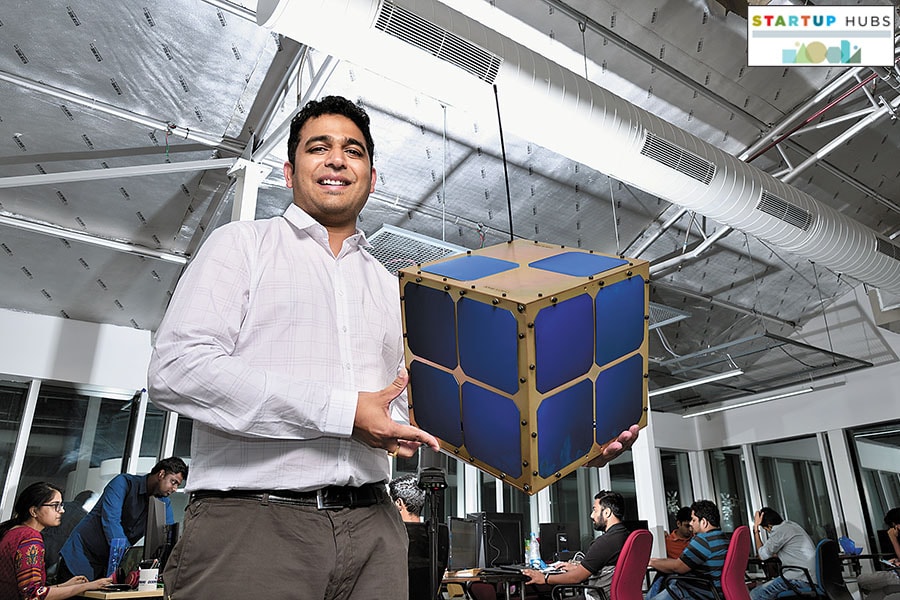

***** Sanjay Nekkanti, CO-founder and CEO, Dhruva Space

Sanjay Nekkanti, CO-founder and CEO, Dhruva Space

Image: P Anil Kumar for Forbes India[br]There are also several central government defence research establishments in the state. These factors have created a very fertile ecosystem, especially for tech startups looking to establish themselves in the city, says Sanjay Jesrani, founder and CEO of Go North Ventures, an investor in the thick of the action in the city. Jesrani is part of the Indian Angels Network and also on the board of The Indus Entrepreneurs network’s Hyderabad chapter.

Some companies, such as Dhruva Space, are even expanding their operations into Hyderabad from elsewhere, drawn by the deep-tech research in the city. Dhruva Space is registered in Bengaluru, but CEO Sanjay Nekkanti is looking to consolidate his venture’s operations in Hyderabad, making small commercial satellites.

“Now I am completely working out of Hyderabad, and one important reason is the access to a lot of hi-tech engineering solutions in the city. A lot of aerospace and defence technology companies are based here, supporting and supplying to programmes of ISRO and DRDO,” he says.There are historical reasons for Hyderabad’s emergence today as a startup hub, says Jesrani.

Successive governments—both of the undivided Andhra state and the new Telangana state—have been proactive and business-friendly. Then there is the combination of the presence of schools like IIITH, the Indian School of Business, the Indian Institute of Technology, the Indian Institute of Chemical Technology and the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, which offered a talent base from which to hire from.

Over the last 20 years, formidable IT services presence was built up in Hyderabad both by Indian companies and multinationals which chose to locate their development centres in the city. Besides, companies including Microsoft, Oracle, Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Salesforce have growing centres in the city.

Jesrani says that many students from the region also went to reputed schools such as BITS Pilani, then went on to gain rich experience in multinational companies and then turned entrepreneurs. They brought their experience home, and “built the DNA of technology” for Hyderabad.

Startups from all over India can also apply to be part of the accelerator programmes at Dlabs, the incubator, accelerator and investment arm of Indian School of Business. “The academia, government and industry work very closely in Hyderabad,” says Aruna Reddy, CEO of Dlabs. “We specialise in taking new startups to market, where there is technology and proof of concept in place, and in helping existing startups to scale.”

Gurugram’s Chakr Innovation, which is building a device that traps the polluting particulate matter in the exhaust of diesel electricity generator sets, participated in an accelerator programme. “They really understood what we needed, rather than force their processes on us,” says Bharti Singhla, co-founder of Chakr Innovation.

Amardeep Sibia, co-founder and CEO at Bengaluru’s Satsure, a venture that is combining satellite remote sensing, machine learning and big data analytics for applications in multiple areas, from agriculture to telecommunications to sustainable development, adds, “They are also unique in the way they leverage the strengths of the ISB faculty.”

*****

Office space uptake in the January-March period this year in Hyderabad surpassed that of Bengaluru, real estate consultancy CBRE reported in April. And for the fifth year in a row, Hyderabad emerged as the city with the best quality of living rating, ahead of other Indian cities, in an annual survey conducted by consultancy Mercer.

“Hyderabad was once seen as a sleepy town, but we now have microbreweries,” says Srinivas Kollipara, who co-founded T-Hub and is the president of Global Entrepreneurship Network (India). The city is also seeing the rise of malls and restaurants and offers good schools and hospitals too, making it conducive for both younger staff and senior-level recruits, who would have school-going children. And barring two hot summer months, the city has a good climate as well.

The funding ecosystem is still very nascent in Hyderabad, says Jesrani. There are a few funds such as Endiya, Sri Capital and Parampara Capital that are actually based in Hyderabad. However, these are all mostly pre-series-A funds.

Second, Jesrani adds, Hyderabad still has a very easy-going culture. In Bengaluru for instance, there is a fairly professional culture and if someone commits to something, they usually follow through on it. But in Hyderabad, in a lighter vein, he says, “I believe the whole Hyderabadi water and the Nizami heritage affects the people in the city.” Three out of ten times, if one has set up a meeting with someone, it’s possible they will be 15 minutes late or once in while someone might even call up and ask if the meeting was still on. That sometimes flows through into the lack of rigour in terms of their planning, execution or follow through, he says.

But much is changing in Hyderabad that hasn’t yet been recognised widely, says Kollipara. With all the office uptake that’s happening today, in five years, those companies will be well settled and will provide both new jobs and be a source of talent in the ecosystem.

There will be a lot more multinational companies, which changes culture again. More jobs and more people from around the country will be coming in, which in turn will change the activities in the city as well—more restaurants, more night life, more theatres, and more culture.

“Essentially, what Bengaluru is today, Hyderabad will be tomorrow and in a much more sustainable way, I believe, because there is a lot of talent here, natively,” says Kollipara. “All of this will come together to make Hyderabad a much more vibrant and alive city with startups coming out of here that will make a national and global impact.”

First Published: Jul 10, 2019, 09:25

Subscribe Now