Cashback, flashback, a while back: How Paytm ended up with a deserted Mall

Paytm Mall aspired to topple Flipkart and Amazon in 2017. Five years later, the valuation has crashed, revenues have dipped and losses have mounted

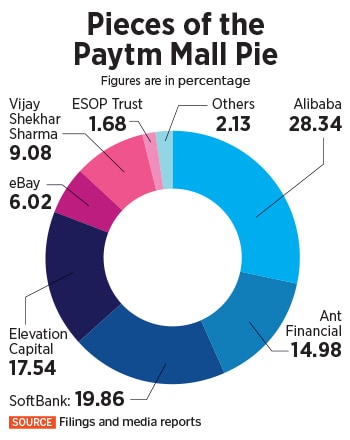

It was a good time for Vijay Shekhar Sharma. In April 2018, the poster boy of fintech payments in India reportedly raised a staggering $445 million (about Rs2,900 crore) from SoftBank and Alibaba for Patym Mall. This gave the ecommerce marketplace of Paytm, which had started operations in 2017, a valuation of $2 billion.

The online retail fight was getting brutal as the ecommerce upstart bared its aspirations to topple Flipkart and Amazon. The weapon identified to cause maximum damage was cashback. While Flipkart, Amazon, Snapdeal and ShopClues focused on discounts, Paytm Mall tried to outsmart all by using the cashback card. With ewallets losing steam, cashback looked like a nice way to play the volume game.

The mood in the Paytm camp was upbeat. “Paytm Mall is eyeing $9 billion in gross merchandise value (GMV) by the end of 2018," Amit Sinha, the then chief operating officer of Paytm Mall, reportedly said. The reason for his bullishness was understandable. In 2017, Paytm Mall had $3 billion in GMV.

After the funding, Paytm Mall planned to step up aggressively over the next twelve months. First, it created an ambitious blueprint to increase the seller base from 75,000 to over 3 lakh. Second, it wanted to expand the same-day and next-day delivery coverage from six percent of the country to almost 30 percent of the pin codes. “Deeper shopkeeper and seller penetration in all pin codes, return customers, stronger logistics network are a few of the things we are working on," Sinha reportedly added.

The founder of Patym also sounded exuberant, and he had all reasons to. The biggest learning, Vijay Shekhar Sharma had remarked in 2018, is that grocery is the fastest growing category in ecommerce. “The consumers come back again. We have a daily needs section in Paytm Mall for that reason," he reportedly said, claiming that around 25 percent of the GMV at Paytm Mall comes from grocery. He projected that the numbers will shoot up to 40 percent. “Groceries would contribute around $3 billion GMV by end of the year (2018)," Sharma predicted. Cashback was in full swing, consumers were coming back to the platform, and there was no reason for Sharma to look back and devise any new strategy.

With Unified Payments Interface (UPI) hitting hard the monetisation model of all payments business, Paytm was left with no choice but to go slow on ecommerce venture.

With Unified Payments Interface (UPI) hitting hard the monetisation model of all payments business, Paytm was left with no choice but to go slow on ecommerce venture.

In May 2018, a month after SoftBank and Alibaba funded Paytm Mall, the ecommerce landscape in India suddenly changed. US retail giant Walmart bought rival Flipkart, reportedly for $16 billion. With Snapdeal and ShopClues struggling with their own issues, and now Flipkart getting acquired by Walmart, it looked like Paytm Mall had a realistic chance to sit on top of the ecommerce heap. The honchos at Paytm Mall pushed the GMV target from $9 billion by the end of 2018 to $10 billion by March 2019. The game of cashback, valuation and cash burn had intensified.

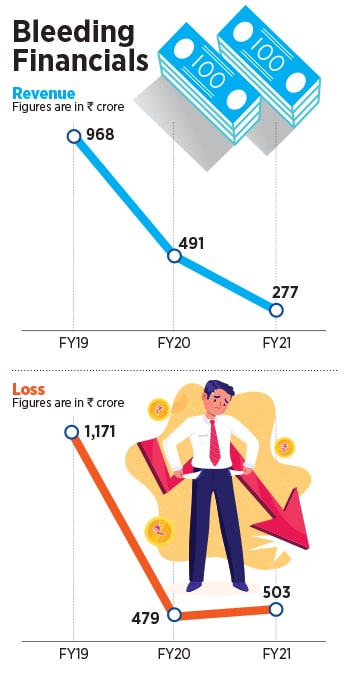

The gambit seemed to be paying off in March 2019. Paytm Mall reportedly posted a revenue of Rs 968 crore for FY19. The losses, though, stood at Rs 1,171 crore. But Sharma was not bothered even a bit. “Hamare paas maa aur baap hai (we have both mother and father)," said a top Paytm official to this reporter in 2019, referring to Alibaba’s Jack Ma and SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son.

With a firm commitment from deep-pocketed investors, there was no need to slow down. In its description of Paytm Mall on its website, Elevation Capital summed up the reason for backing it. Paytm Mall is a horizontal, B2C ecommerce platform enabling next ‘revolution’ in commerce, the VC funded outlined.

With a firm commitment from deep-pocketed investors, there was no need to slow down. In its description of Paytm Mall on its website, Elevation Capital summed up the reason for backing it. Paytm Mall is a horizontal, B2C ecommerce platform enabling next ‘revolution’ in commerce, the VC funded outlined.

Seven months later, in October 2019, there were apparent signs of revolution. Sharma claimed that the Paytm Mall business was close to breakeven. “It has $3 million Ebitda loss a month, $1.2-1.3 billion in run rate, and does 2.75 lakh to 3 lakh orders a day," he reportedly said. "We have money in the bank, after a year, Paytm Mall would break even for sure," he added. By the end of 2019, Paytm Mall’s valuation soared to $3 billion.

Fast forward to May 2022. The valuation has reportedly crashed from $3 billion to $13 million as two of its prime backers—Alibaba and Ant Financial—have pressed the exit button. What has also alarmingly dipped is the fiscal health. From a high of Rs 968-crore in FY19, the revenue tumbled to Rs 277.4 crore in FY21. Though the losses during the same period dipped, they are still more than the revenues: Rs 503.8 crore in FY21.

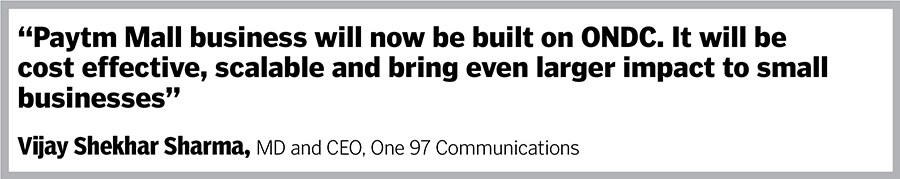

After years of burning loads of cash, Sharma claims he has hit a cost effective way to run Paytm Mall. Last week, on May 16, the company informed its move to join the government-backed ecommerce platform, Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC.) “Keeping in mind our attention to building an open platform for ecommerce," Sharma tweeted, “Paytm Mall’s s business now be built on ONDC." He added that the business will be “cost effective, scalable and bring even larger impact to small businesses".

"We are focused on our transition to build a sustainable business in partnership with ONDC and are excited about the future of ecommerce in India," a company spokesperson said in an email to Forbes India. As part of the shift in the business direction of the company, Paytm E-commerce Private Limited (PEPL), the parent entity of Paytm Mall, has seen exit of early investors.

The company, however, denied that there has been a cut in valuation. “The exit price of any investor(s) in the company via capital reduction process is not reflective of the valuation of the company and neither does the exit have any link to any FDI laws," the spokesperson added. The cash balance, the email underlined, is significantly higher than the quoted number in media reports, which establishes that the suggested low fair market valuation is completely inaccurate. The spokesperson did not share the financials for FY22.

Industry experts paint a different picture. The fall of the Mall, they reckon, has to be understood in the game of valuation, and what Sharma was trying to build. “He aspired to be Alibaba of India," says Ankur Bisen, senior vice president (retail & consumer products division), Technopak. The irony, though, is the aspiration was flawed.

Industry experts paint a different picture. The fall of the Mall, they reckon, has to be understood in the game of valuation, and what Sharma was trying to build. “He aspired to be Alibaba of India," says Ankur Bisen, senior vice president (retail & consumer products division), Technopak. The irony, though, is the aspiration was flawed.

Bisen explains that the core of Alibaba and Paytm was payments, and then Alibaba kept adding layers to it. Sharma too wanted to copy the model. There was a big problem, though. “Alibaba’s growth in China happened under a controlled regulatory business and political landscape," points out Bisen. The Chinese company’s growth to a large extent happened under a monopolistic environment. Paytm and Mall, on the other hand, operated in a fierce competitive environment. While in 2018, Mall was stacked against Walmart and Amazon on one side, over the next few years a new set of players, led by hyper aggressive Reliance and Tata, entered the fray.

The aspiration to sell everything—from low-ticket item to high-priced goods—also boomeranged. “Where was the differentiation," asks a venture capitalist, requesting anonymity. Paytm Mall, he reckons, had almost become a copycat of ShopClues in trying to woo buyers from Bharat—Tier II and beyond. Sharma also did not realise that in ecommerce you need to get your math right. “One plus one is not eleven but two," the venture capitalist says. Millions of users—customers and merchants—that the parent company always boasted of could not translate into users of Mall.

The realisation of losing the game started to sink in in 2020. In September, the company did its best to streamline operations to improve its unit economics. There was a drastic reduction in assortment sizes, cashbacks, discounts and promotions. “Our efforts are to become profitable with hyperlocal outreach and initiatives which have already started giving positive results," then Paytm Mall COO Abhishek Rajan reportedly said.

The efforts to cut corners also led to something that Mall could never fix from day one: Fulfilment.

From FY19, Paytm Mall cut logistics costs by relying on third-party network of delivery firms. The move, point out observers, turned out to be a blunder. Jack Ma, says another VC requesting not to be named, built his business empire on three pillars. For him, the VC underlines, ecommerce platform was the king, payments was the queen, and fulfilment was the prince. “Sharma had the queen, started Mall to become the king, but sadly he ignored the prince," he says. Ecommerce businesses, the funder reckons, is not built on loads of cash only. “It’s a high-burn business and takes years to achieve scale and profitability," he says.

The most crucial thing needed to build a sustainable ecommerce marketplace is fulfilment. “Look, what Amazon and Flipkart have done. They controlled end-to-end experience," says one of the VCs that backed an ecommerce marketplace that shut shop a few years back. Marketplace, he points out, doesn’t only mean making buyers and sellers meet. Paytm Mall wanted sellers and brands to stock and deliver the products in order to cut the operating cost.

Once losses started mounting, Mall had no choice but to cut down cashbacks. “The user stickiness was not built on experience and service, but cashbacks," says the VC quoted above. Consequently, the consumers started deserting Mall. The company reportedly started scaling down B2C business, shutting fulfilment centres and downsizing. A spate of high-profile exits made things worse. Amit Sinha exited after a decade in 2019, and so did others at Paytm over the next year or so. What made matters worse were alleged cases of fraud popping up in 2019. Paytm Mall reportedly engaged consulting and audit major EY to look into cashback fraud involving some its employees and merchants.

With Unified Payments Interface (UPI) hitting hard the monetisation model of all payments business, Paytm was left with no choice but to go slow on ecommerce venture. “Valuations don’t build business. Look at what is happening to Zomato and Paytm after they got listed," says Bisen of Technopak. “The fall of Mall was a foregone conclusion."

First Published: May 23, 2022, 16:01

Subscribe Now