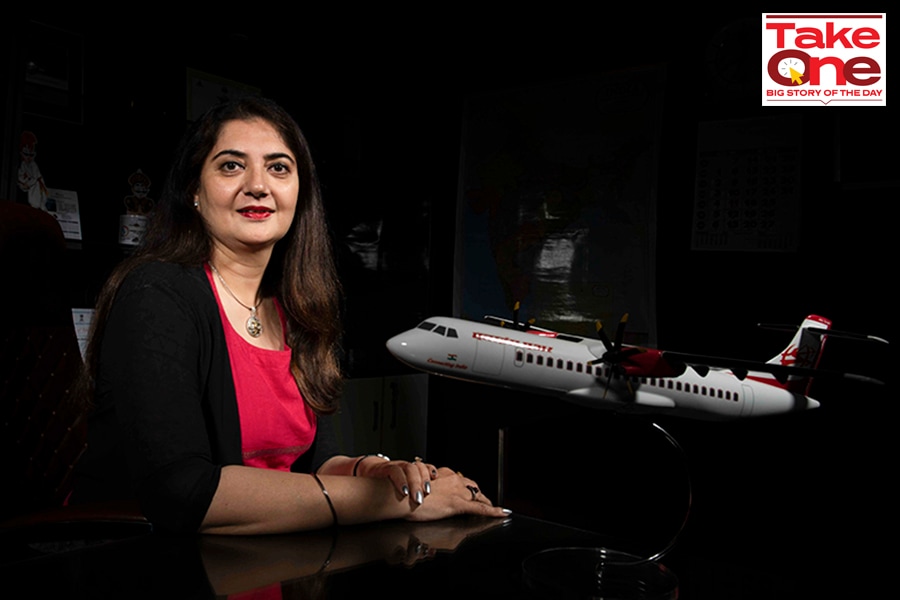

India's first woman airline CEO has ambitious goals. Can she take off?

The first woman pilot hired by Air India, Harpreet A De Singh is now charged with turning around the fortunes of its subsidiary Alliance Air

Image: Amit Verma

Image: Amit Verma

For much of her life, Harpreet A De Singh has been busy shattering glass ceilings. In 1988, as a 21-year-old, she was the first female pilot to be selected by India’s flagship carrier Air India to fly its aircraft, at a time when the government-owned airline ruled the Indian skies. In the mid-1990s, she became the first female instructor for Air India’s pilots before going on to become the country’s first female chief of flight safety, in 2015.

Even then, by her own admission, she had not seen this one coming. In fact, she hadn’t even applied for it, nor was she called in for an interview. Yet, it was perhaps her penchant to break barriers and her long-drawn credentials at Air India that propelled her to become India’s first female CEO of an airline late last year.

“They must have seen something,” Singh says. “When you"re going up, people are watching you. They know how you’re performing and how you are working. Somewhere down the line, they may have trusted my ability.”

On November 3, Singh took charge as the CEO of Alliance Air, the New Delhi-headquartered subsidiary of beleaguered national airline, Air India. “I was pleasantly surprised they had thought of me for this role,” the 54-year-old told Forbes India over a video call. “I knew that I was up to take up the challenge because I have had one advantage, having worked 360 degrees in an airline in the past.”

That’s precisely what Alliance Air also desperately needs to turn around its fortunes in addition to laying plans for its next phase of growth. Ever since it was carved out of the government-owned Indian Airlines in 1996, largely as a feeder service for Indian Airlines, the company has nothing significant to show on its records. The airline has been operational for over 25 years, and yet it barely finds a spot among India’s top five. The company has 18 operational aircraft, all of which are Toulouse-manufactured ATRs, which are short-haul regional airliners with 72 seats.

A significant number of its routes are in India’s small towns, including Dharamsala, Dimapur, Pantnagar, Ludhiana, Pathankot. In contrast, IndiGo, currently India’s largest airline by market share, began operations a decade after Alliance Air, and currently controls nearly 60 percent of the market. The airline operates a fleet of 279 aircraft, a bulk of it in the Airbus A 320 category.

“I can see so many things which I want to fix,” Singh says. “I know it will happen slowly and steadily, but we will definitely fix it. It takes time and we have to have the willingness and passion to do it.”

Passion and grit aside, it may not be as easy as Singh might want it to. For one, the airline continues to operate as a subsidiary of the debt-laden Air India group. The government has also not made Alliance Air a part of the stake sale plan for Air India, which means that the government will likely hold control of the airline in future. The Air India stake sale has been moving at a dawdling pace since it was first announced in 2018.

Second, India’s aviation sector has undergone significant changes since Alliance Air began operations two decades ago. Today, 90 percent of the Indian aviation market is controlled by the private sector, led by IndiGo, SpiceJet, and Vistara among others. Between them, these airlines have also been foraying into routes traditionally operated by Alliance Air.

“Currently Alliance Air is an ATR operator that connects hubs to smaller Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities and is also a feeder to Air India,” says Sanjiv Kapoor, the former chief operating officer of SpiceJet and senior advisor at New York-based Alton Aviation Consultancy. “It is not an independent airline in that it does not have its own distribution or website and commercial functions appear to be handled by Air India. It will need to convert to an independent entity and stand on its own feet.”

Despite all that, Singh has set some ambitious plans for the airline.

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Big dreams

To begin with, over the next few months, the airline is looking to expand its capacity as well as routes, including international ones to be commercially viable. “It"s exciting to know that you can do something to ensure that an airline, which was not very well known and sitting as a subsidiary of a very large airline, can come to the forefront and provide support in every way to the passengers,” Singh says.

In February, as part of its plan to increase its existing fleet size, the company announced the purchase of two made-in-India aircraft, which Singh reckons is in line with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious Make-in-India initiative. The company signed an agreement with Bengaluru-based Hindustan Aeronautical Limited (HAL) to purchase two Dornier 228 turboprops and is expected to start commercial flights on those aircraft shortly.

“Within the three months that I"ve taken over, we’ve taken a lot of important decisions,” Singh says. “We’re the first airline in the country to go ahead with what people would call a risky adventure, which is to purchase aircraft made in India. But to me, we need to encourage our own made-in-India products.” The 19-seater light transport aircraft are likely to be deployed in the country’s northeast, where airlines have been looking to increase their operations to.

The plan would also play well into the company’s focus on the government’s regional connectivity scheme (RCS), launched in 2017. Udan, as the scheme is called, is aimed at enhancing connectivity to remote and regional areas of the country and making air travel affordable. Under the scheme, nearly half of the seats in Udan flights are offered at subsidised fares, and the participating carriers are provided a certain amount of viability gap funding, an amount shared between the Centre and the states concerned.

“Right now, regional connectivity is our scheme,” Singh says. “I want to connect to people, I am passionate about bringing people together all over the country.”

Besides, the airline is also planning to ramp up on its commercial operations, both newer routes and cargo operations. Over the last few months, it has begun operating in routes like Mumbai-Goa, Mangalore-Mysore, and Bengaluru-Kozhikode. “We also have to survive as an airline,” Singh says. “We have to be commercially viable. That"s equally important.”

Currently, the airline flies to 44 destinations in the country. “Alliance Air is a good feeder, a good regional connectivity airline, where the Tier-2 and -3 cities can get connected,” Singh says. “But having said that, we are going beyond RCS structured routes into pure commercial routes. Both Mumbai-Goa and Mysore-Mangalore are not RCS sectors, but we have still gone ahead.”

That also means, apart from buying the 19-seater Dornier aircraft, the airline is also looking to purchase more ATR aircraft. “We are looking to expand,” Singh says. “Apart from the two Dornier coming in, we’re also going in for an ATR 42 lease. We’re trying to get into Shimla operations and some of our other operations, where there was a payload restriction, with the ATR 72. If everything goes well, we will be adding to our ATR fleet as well.”

Adding more aircraft to the fleet will also allow the airline to start looking at options outside the country, particularly in India’s immediate neighbourhood. “But that would not happen immediately due to Covid-19 restrictions,” Singh says. “On the international front, we may look at Jaffna and some of our neighbouring countries, but it will take us some time. Today, we are not allowed to operate at 100 percent capacity.”

India had halted airline operations last March, after which the government has been slowly permitting airlines back into service. As of March, the government has allowed 80 percent of the capacity to be used by airlines, after starting with 33 percent capacity at the end of May when the country lifted lockdown restrictions.

“What is the best path forward is for them and the government to decide,” adds Kapoor. “I would expect domestic regional connectivity to continue to be an area of focus for the government. If the airline goes international and gets mainline Boeing or Airbus aircraft, then the question arises whether the goal of the government to largely get out of the business of running airlines will be fulfilled. Some close-range regional international that can be served by their fleet of ATRs may, however, be a possibility.”

Taking it slow and steady

Singh, meanwhile, isn’t in any rush. “First, we have to come back to normalcy and then gradually work towards the international,” Singh says. “The trend is positive. We can see that our passenger numbers per day are steadily increasing. We were down to hardly anything on a daily basis, then it grew to less than 2,000 passengers a day before going to 3,000 in November. In February, we crossed 4,000 passengers a day.”

A slowdown in passenger movement had meant that many Indian airlines had been busy pivoting towards cargo operations to sustain themselves. This year, Indian airlines are expected to post a net loss of Rs 21,000 crore following travel restrictions amid the Covid-19 crisis, according to rating agency ICRA, and will also require an additional funding of Rs 37,000 crore from FY21 to FY23 to recover from the losses and debt.

That has meant Alliance Air has also initiated proposals to convert two of its aircraft for cargo operations. “Two of our aircraft are already getting ready to do freight operations along with passenger combination flights,” Singh says. “That could likely be deployed into transportation towards remote areas. We have also helped the government of India to transport vaccines and other urgent material into distant areas. We are progressively increasing our insight into the cargo operation as well.”

Much of that decision to ramp up its play in the cargo segment also came from Singh’s expertise as the head of flight safety at Air India, where during the lockdown, the company had been engaged in evacuation and cargo movements. “I did all the coordination to make that cargo operations happen because we had to do a full safety risk assessment, we had to make sure the procedures were in line and we were doing something which we had never done before,” Singh says. “And we needed a lot of regulatory approvals. We were transporting through Vande Bharat with restrictions. So, coming from that background, I know that a lot of work was done for cargo.”

That means, the company is likely to go head-to-head with many private companies who have also been flocking to smaller towns to propel growth. “In fact, what is challenging for me and what some of my predecessors did not have is the kind of competition,” Singh says. “But now I’m faced with a huge challenge because we also have our competition which is really expanding on ATR. And somehow ATR seems to be the new trend. Airlines are seeing the merits in connecting Tier-2 and -3 cities. It"s going to be a challenge, but we have our ways and thought processes built around that to overcome this challenge, and I’m sure we’ll overcome.”

In October, Alliance Air had said it had made an operating profit, for the first time since inception, of Rs 65.09 crore for FY20. While the company did go on to make a net loss of Rs 201 crore during the period, it had also managed to rake in revenues of Rs 1181.15 crore.

“This airline has been running for many years and the very first-time last year, it did make an operating profit,” Singh says. “But unfortunately, Covid came in, so it immediately became loss-making. But it was a good step. Our first target is to come back to the operating profit. Covid has really messed up the whole situation and we’re not even operating at full strength.”

Singh now wants to take the airline into the black in the coming years. “My goal is to make net profit,” she says. “As long as I’m here I’m going to stay focussed on that goal and I want to make it happen. But it will take some time as these things don"t happen quickly. After all, there are historical debts that we have to clear for last so many years.”

“In my mind, the most attractive space that is available is largely in underserved Tier-2 and -3 cities, which can be quite lucrative especially in the post-Covid-19 era as people migrate away from trains and buses,” says Kapoor of Alton. “The rest of the market has a lot of competition and it will not be easy to go up against the established players head-to-head.

“For too long, Air India has been a CEO-centric organisation,” says Jitender Bhargava, a former executive director of Air India and the author of The Descent of Air India. “Whenever a new CEO comes, they do away with everything that the previous one had done. Having said that, Singh’s initiatives are a welcome move, but one has to be realistic about them.”

Breaking the ceiling

Much of Singh’s ambitions to fight it out in a market dominated by private companies also comes from her years of being battle-hardened.

As a young girl and an NCC cadet, Singh, the daughter of an Indian Air Force (IAF) officer, had always wanted to fly. “I just loved seeing airplanes fly,” Singh says. But she couldn’t join the IAF, her first love, as the existing rules did not allow women to fly. The IAF had inducted its first batch of female pilots only in 1994.

“I"ve had so many ups and downs, and many times you are not given what you truly deserve,” Singh says. “But I"ve taken that as a gift from the almighty because it allows you to overcome a challenge and to learn new skills.”

In 1988, Singh was selected by Air India as its first woman pilot. “I made it through the Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Udaan Academy (IGRUA) which I still owe a lot to,” Singh says. (The IGRUA is a pilot training institute located at Fursatganj Airfield, in the Amethi district of Uttar Pradesh. Established in 1985, it was the first such institute in India.)

But much before that, Singh had done her private flying licence in Hisar, in Haryana. “I still remember there were no women that time and I was told, there"s no toilet for the women.” That meant she had to rent a house many miles away and commute on her moped through the jungles every day, to get to her training institution. “It was just a faith in god and a belief that nothing will happen,” Singh says of those days.

After her selection at Air India, however, Singh’s career was cut short by a health problem. A brain scan indicated a minute possibility that Singh might black out at the sight of lightning. Soon after, she headed to the US to convert all her licences into “US licences” before becoming a trainer. “I got reselected by Air India as an instructor and was the first lady who was teaching pilots,” Singh says.

Over the next few years, Singh worked across various departments of Air India including training, operations, flight planning, flight dispatch, quality, and even audit. “I used to write all the safety procedures, documents and get regulatory approvals,” Singh says. “I broke a lot of barriers, but I didn"t think too much about it because it was just a good opening for other women also to come up”.

While her new role means she has a lot on her plate, Singh is only getting started. “I really want to prove that you do not need to be unfair or corrupt or do anything wrong to be successful,” Singh says.

All her life, Singh has never given up a good fight. It’s unlikely that she will now.

First Published: Mar 03, 2021, 17:04

Subscribe Now