Inside Tata Projects, India's newest infra builder

The engineering procurement and construction arm of Tata Sons is putting building blocks in place to emerge as a premier infrastructure player in the next decade

Ninety minutes from central Delhi, the outline of a vast new project is taking shape. Here in the exurb of Jewar, amid 5,000 acres of verdant fields, construction crews have moved in to begin work on what is slated to become India’s largest airport. Scheduled to open in late 2024 with an initial capacity of 12 million passengers, the project has been billed as among country’s finest infrastructure build outs. Concessionaire Zurich International Airport expects it to be among the finest airports globally.

In many ways, the groundbreaking ceremony in June of the Noida International Airport was also a coming out party for Tata Projects, the engineering procurement and construction or EPC arm of Tata Sons. The business, housed as a subsidiary of Tata Power, has been steadily expanding the scope of its activities over the last decade. It has gone from being a sleepy company based in Hyderabad, which worked mainly on projects in the power sector to a leading urban infrastructure player.

It is now working on three of the largest infrastructure projects in the country—the Noida Airport, the Mumbai Trans Harbour Link and the new Parliament building. Industry insiders say that the business received a fresh impetus after Tata Sons’ acrimonious break up with the Shapoorjis. (In some bids, like in the case of the Parliament building, Tata Projects went head-to-head with Shapoorji. Shapoorji did not submit a financial bid).

Vinayak Pai, who took over as managing director in June, says the group that has shown it can innovate with TCS now also wants to show that it can build. “From what I have heard, they (Tata Sons) want us to be the signature organisation in the group that can signify our ability to do complex things," he says.

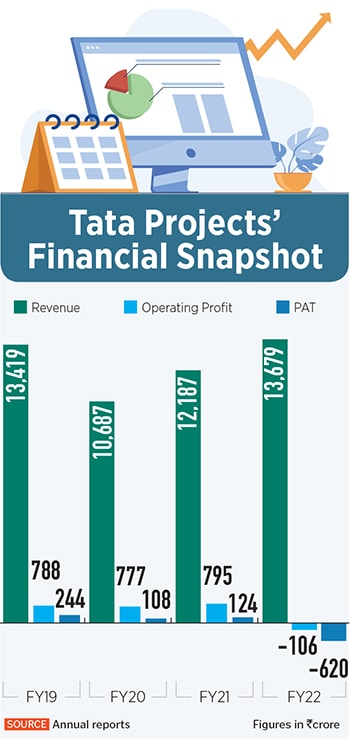

Pai knows he has his work cut out, for financial metrics of the business need improvement. Tata Projects, with a Rs45,000 crore order book, has shown it has the ability to get business. But in the year-ended March 2022, the company lost Rs605 crore on a topline of Rs13,758 crore.

A part of that was on account of legacy contracts, Covid related delays, and a sharp rise in commodity prices that also resulted in reduced margins. And there were some projects that had money stuck with the government. Pai agrees that driving profitability will be a key challenge and says he hopes to see very different financial metrics. The company says it has started putting the building blocks in place. Its performance would be a benchmark for the health of the infrastructure sector. The government has upped capital expenditure spending with an increase of 57 percent to Rs1.75 lakh crore in the first quarter of the current fiscal.

As India moves towards a $5trillion economy, the building blocks to power this growth are being put in place. CRISIL estimates this opportunity at a total of Rs110,000 lakh crore. Think roads, power plants, bridges, dams, large buildings, airports, ports, waterways, tunnels, and the list goes on.

At the same time, the peculiarities of Indian infrastructure market means that global companies—Bechtel, Kiewit, Saipem—haven’t found it worth their while to have a meaningful presence in India.

The chief reason for this is the L1 bid system that the government follows, where the lowest bidder is awarded the contract. Global companies have found it hard to adhere to a system where price alone determines the awarding of the contract. Instead they prefer to operate in very specific areas. “One area where they can operate is if there are technology aspects as with say high speed corridors or metro networks," says Jagannarayan Padmanabhan, director, CRISIL Market Intelligence & Analytics. For smaller contracts up to Rs10 crore, government departments have now started using a mix of financial bids and technical criteria in awarding contracts.

In addition, there have also been problems with delayed payments on account of disputes, commodity price escalation as well as cost escalation. All this has resulted in EPC companies suffering from poor profitability. This was pronounced in the road sector, after which the government largely moved the risk onto its books by agreeing to pay the road builder based on the work completed. The toll risk was eliminated.

This is a problem readily acknowledged by Pai. “The company is working on a transformation drive and the results should be visible in the next 12-18 months," he says. It is important that Tata Projects gets this right as India needs several companies that can execute infrastructure projects at scale. Rival Larsen and Toubro has been able to de-risk by taking up projects outside of India. But even then its growth rates have been far from stellar. In the last decade sales have compounded at nine percent a year to Rs171, 029 crore and profits at 6 percent a year to Rs11669 crore, resulting in a PAT margin of 6.8 percent.

This is a problem readily acknowledged by Pai. “The company is working on a transformation drive and the results should be visible in the next 12-18 months," he says. It is important that Tata Projects gets this right as India needs several companies that can execute infrastructure projects at scale. Rival Larsen and Toubro has been able to de-risk by taking up projects outside of India. But even then its growth rates have been far from stellar. In the last decade sales have compounded at nine percent a year to Rs171, 029 crore and profits at 6 percent a year to Rs11669 crore, resulting in a PAT margin of 6.8 percent.

In its plan to turn things around, Tata Projects plans identified four key pillars—business, processes, people and technology. According to Himanshu Chaturvedi, chief strategy officer at Tata Projects, the company has consciously moved its order book from the power sector to newer focus areas of urban infrastructure, transportation, metals and water.

There is also newer discipline being brought about in the bidding process. In order to develop the execution skills for complex projects, infrastructure companies need to constantly move up the value chain by incrementally bidding for larger projects. But the key here is not to sacrifice too much margin. “We may bid for some projects for the prestige value. For instance, the Parliament building gives us bragging rights for the next century. Here we would have to accept lower margins. But this is a conscious call and across projects we have now put in more bidding discipline," explains Sanjay Sharma, chief financial officer at Tata Projects.

Contracts now come with built-in escalation clauses so that a sudden rise in, say, commodity prices or delays in land acquisition doesn’t impact profitability. The government is now also willing to hand out compensation for delays after an arbitration award. Earlier, the wait for companies was longer as they had to wait for the outcome of an appeal. As a result, interest costs kept piling up hindering their ability to bid for newer projects. The net result of this discipline is that at present L1 bids account for only Rs1691 crore, according to the FY22 annual report.

Contracts now come with built-in escalation clauses so that a sudden rise in, say, commodity prices or delays in land acquisition doesn’t impact profitability. The government is now also willing to hand out compensation for delays after an arbitration award. Earlier, the wait for companies was longer as they had to wait for the outcome of an appeal. As a result, interest costs kept piling up hindering their ability to bid for newer projects. The net result of this discipline is that at present L1 bids account for only Rs1691 crore, according to the FY22 annual report.

On the technological front, there are plans to use extensive modeling while executing large projects “After agriculture, construction is the least digitised industry," says Chaturvedi. In an industry that operates at 5-7 percent PAT margins, proper modeling can result in cost savings. A building information system modeling is being put in place.

Another issue the industry faces is the lumpy nature of contracts. How does one plan hiring for a large order without ensuring a drag on profitability if those personnel are sitting idle the following year? Working with contractors is one way out the company is exploring.

Lastly, there are the businesses that Tata Projects wants to get into. Over the last decade, it has reduced its reliance on contracts in the power sector and these account for only about 20 percent of business now. Urban infrastructure is seen as a huge growth opportunity with these projects bringing both its engineering and project execution skills to the forefront. But the bread and butter will be contracts in areas such as oil and gas, metal and mining and water. These will help steady the ship as far as margins are concern. Green energy is the last area Tata Projects plans to get into.

If all goes well over the next three-four years, Tata Projects would have completed the Noida Airport, the new Parliament building and Mumbai’s Trans Harbour Link, cementing its position as a India’s third EPC company with healthy profitability. It would also have the potential to list at Rs10,000-15,000 crore valuation. While Pai is tight-lipped on those plans, it has the potential to unlock value for investors in Tata Power as well as give Tata Sons another marquee listed entity.

First Published: Nov 28, 2022, 15:08

Subscribe Now