Markets refuse to sell off. What is driving this?

Indian markets have proven resilient over the last six months. Declines have been shallow and short-lived since the collapse in March 2020

Over the past six months, going short on the Indian market has been a fool’s errand. Rising interest rates, higher inflation numbers and peak valuations have proved insufficient to dent the index rally that started after the collapse in March 2020. Since then, market declines have been shallow and short-lived. Buyers have been waiting on the sidelines.

As things stand, the Nifty 50 quotes as a price multiple of 22 times while its midcap counterpart the Nifty Midcap 100 is at a 26 multiple. Both are the highest valuation numbers seen in the last decade and look set to sustain.

These numbers come at a time when Indian companies are facing rising challenges on account of slowing demand, supply chain bottlenecks and rising costs. What then explains the resilience of Indian markets?

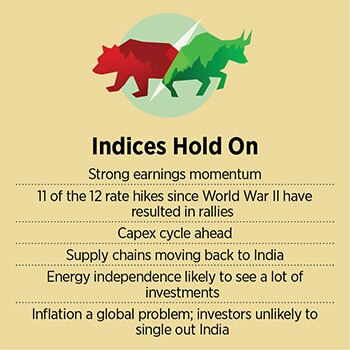

“Earnings have been strong," says Gautam Duggad, head of research, institutional equities at Motilal Oswal. The brokerage has put an FY22 Nifty earnings target of Rs730, which has been led in large part by an increase in earnings from metals companies. If this number is achieved, this would make it the best earnings year for the Nifty since FY11. Other sectors like IT, oil and gas, banking have also picked up the slack left by slowing earnings in consumer companies. Motilal is targeting Rs870 Nifty earnings for FY23.

In addition, there are opportunities for earnings to continue to grow as companies shift production back home and energy independence becomes a theme for the current decade. With an investment cycle moribund for much of the last decade, Kenneth Andrade, chief investment officer at Old Bridge Capital Management, sees ample room for growth in spending on new capacities over the next decade but cautions that this is likely to be the decade when inflation takes off.

Unlike in the past, rising inflation and higher interest rates come at a time when India’s macroeconomic framework (albeit deteriorating) has been very strong. There are no large imbalances in the current account, forex reserves are at all-time highs and at about seven percent inflation is lower than in the US. “Chances of a hard landing this time appear low," says Venugopal Garre, managing director at Sanford Bernstein. “Inflation is a global problem now and it is unlikely investors will single out India." He argues that in any case India’s macro has been sluggish and can’t get any worse from here.

Rising inflation has taken Indian bond yields to 7.1 percent, and while there is still a 400 bps difference between Indian and US yields it remains to be seen how much those yields narrow. If investors get 3 or 3.5 percent for the US 10 year, the relative attractiveness of Indian equities would decline, taking flows away from India.

Rising inflation has taken Indian bond yields to 7.1 percent, and while there is still a 400 bps difference between Indian and US yields it remains to be seen how much those yields narrow. If investors get 3 or 3.5 percent for the US 10 year, the relative attractiveness of Indian equities would decline, taking flows away from India.

That situation, say market participants, has already played out over the last six months. Starting October 2021, foreign institutional investors have sold Rs228,000 crore ($30.4 billion) of Indian stocks. Still, this has not resulted in a meaningful correction as domestic investors have filled the gap. Domestic institutions bought Rs167,000 crore in the same period. Systematic investment plan inflows have also trended up and stood at Rs12,300 crore for March 2022.

Still, the main worry for investors is the rise in interest rates. While the rate hike cycle has commenced in the US no one knows how far it will go. Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers dismisses talk of rising interest rates torpedoing markets. “The data doesn’t support this," he says pointing out that since World War II, the US has had 12 cycles of rising interest rates and 11 of them have seen market rallies.

According to Mukherjea, the reason central bankers hike rates is to elongate the recovery rather than crashing the cycle. If that is the case then the global recovery, which is likely to see a capex boom on account of supply shortages is probably 24-36 months away from the end of this economic cycle.

The lack of bubbles is the other factor in support of market valuations. Apart from new digital companies as well as the IPO market, one struggles to find excessive valuations anywhere. In places where there has been no earnings growth – for instance, in consumer companies, stocks have been stagnant.

In places where earnings have come through like metals and banking, stocks have rerated and may still have some way to go. There is no excessive credit growth. Real estate prices have slumped for the last eight years at least. And Indian inflation is not as worrying as, say, the US 8.5 percent number as our monetary and fiscal stimulus were between 1-2 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The rest was mostly in the form of loan guarantees for small and medium companies. (Compare this to the US that pumped in $10 trillion into a $20 trillion economy).

For now, the Sensex has been largely stagnant since October 2021 when it hit an all-time high of 61765 on October 18. Since then there have been three bouts of selling brought about by a tightening rate environment as well as a proposed reduction in the balance sheet of the US Federal Reserve. The most serious sell off came on February 24, the day Russia invaded Ukraine when the Sensex fell five percent. Over the course of the next month, it recovered all those losses. There were some technical factors at play here – the inflows into ELSS (equity linked savings schemes) in March due to the tax saving deadline and the deferment of the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) IPO.

Importantly, the last two years have also seen the market move away from its excessive reliance on the Indian consumer driving earnings. Consumer spending still accounts for 56 percent of economic activity but its reliance on Nifty earnings has reduced, making its valuation foundation more stable on metals, IT and banks. While this may no longer be a time for indiscriminate buying of stocks, the markets are unlikely to penalise well-planned purchases.

First Published: Apr 18, 2022, 13:15

Subscribe Now