“I cannot explain (the FII outflows). In fact, if I didn’t know and you asked me to guess, I would have said FIIs were buyers. It is possible passive emerging market ETFs were a large part of the selling, as people have soured on China. It’s worth pointing out that the FII numbers alone don’t paint a complete picture. Some foreign investors use options and structured products to access the Indian market. Also, some of the money could be Indians managing their funds offshore," says Mark Matthews, managing director and head of Asia research at Julius Baer.

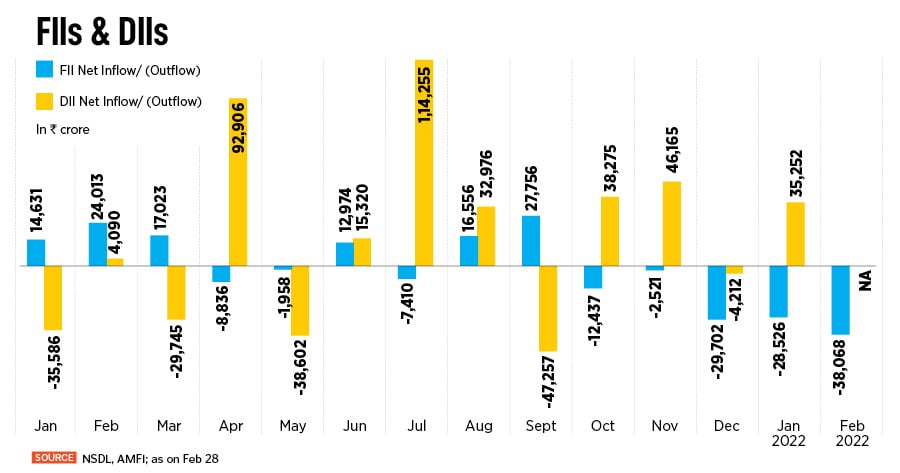

This is not a sudden change of heart, or a bolt from the blue. FIIs have been net sellers in India since October last year (see chart) in response to the changing monetary policy stance of most global central banks, and more specifically the US Federal Reserve.

“Foreign investors started to grapple with the fact that inflation wasn’t transitory and interest rates, at some point in 2022, would have to rise," says Andrew Holland, chief executive officer, Avendus Capital Alternate Strategies.

In such a scenario, foreign investors typically hedge risks by trimming allocations in commodities, emerging markets, and emerging market currencies, Holland explains. In the last six months, FIIs have taken out over $12 billion from secondary markets in India.

The government’s ambitious borrowing plan of around Rs 10 lakh crore, coupled with muted corporate earnings growth, hasn’t helped turn the bearish sentiment of FIIs. Plus, the valuation of Indian stocks is believed to be relatively expensive in relation to emerging market peers.

![]()

“It is true valuations are not on our side but we are confident of earnings momentum. Already, the corporate profit to GDP ratio has risen from 1.7 percent to 2.4 percent, but we think it can get back to its long-term average of 4.5 percent. For seven years Nifty earnings growth was in the low single digits, we see the next three years at 20 percent plus annualised," says Matthews.

India’s market capitalisation-GDP ratio is at a 15-year high of 116 percent versus its long-term-average of 79 percent, suggesting that valuations are relatively frothy at current levels.

Mihir Vora, senior director & chief investment officer, Max Life Insurance, says there is a possibility of FIIs rebalancing investment portfolios with some degree of value buying. “The foreign selling in India begins around October 2021 and it coincided with a substantial outperformance of the Indian markets versus most other emerging markets. Valuations had become expensive for India," he adds.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dramatically worsened the outlook for global macroeconomic stability which in turn has deepened the sell-off in markets. The US Fed’s hawkish tune, signalling a rate hike in March, had already spooked foreign investors, and the escalating geopolitical tension has made investors a lot more cautious and risk-averse.

![]()

Macro challenges

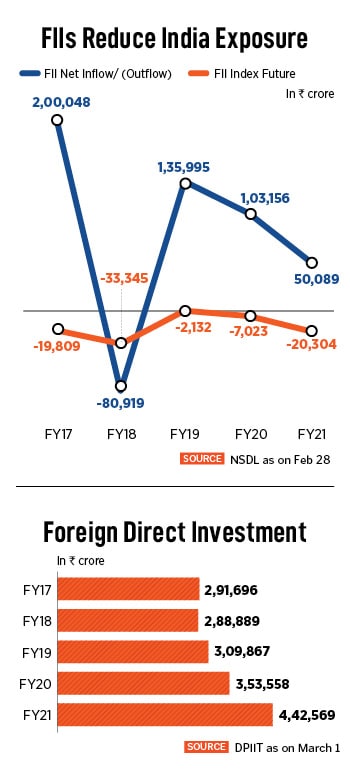

The looming threat of the US Fed tapering asset purchases has pushed FIIs to book profits from India investments—the best performing emerging market in terms of returns—and rejig the investment portfolio.

Over the past few months investors have braced for an imminent rate hike of up to 50 basis points by the US Fed as it tries to rein in high inflation. This has stoked fears of a slowdown and turmoil in financial markets as asset prices readjust.

“The US Federal Reserve has been behind the curve and so we have been expecting a 50 bps increase. We felt that at some point this will have an impact on global growth that could lead to recession," says Holland.

![]() A rate hike in the US can potentially drain out liquidity and stem inflows into financial markets. Also, higher rates in the US may skew the risk-reward ratio against most emerging markets, making them relatively less attractive for FIIs as they increase investments in developed markets.

A rate hike in the US can potentially drain out liquidity and stem inflows into financial markets. Also, higher rates in the US may skew the risk-reward ratio against most emerging markets, making them relatively less attractive for FIIs as they increase investments in developed markets.

Earlier, Holland expected FIIs to return to emerging markets like India in the second half of the year, since he believed it was likely that the US Fed would do a U-turn in July and, in a bid to support a sinking global economy, refrain from further rate hikes.

But the quick turn of geopolitical events over the past couple of weeks has led to a shift in expectation on rate hikes.

“With the war between Russia and Ukraine, the question now is whether the US Fed will increase rates given the problems the global economy might be facing with all the sanctions that will probably hurt Europe more," Holland says. Nonetheless, he has factored in a rate hike of 25 basis points.

Besides, in relation to other emerging markets, India is more vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, commodity and crude oil price shocks arising from the conflict.

India vs emerging market peers

Crude oil at a multi-year high of $113 per barrel—at a time when India’s current account deficit is widening and inflation has crossed 6 percent—has put India in a tough spot. This stands to hurt corporate margins and corporate earnings across sectors, excluding oil and gas and metals. The upcoming state elections will also add to market volatility in the near term.

“An immediate factor working against India is the rise in oil and commodity prices. India is perceived to be more vulnerable to oil prices compared to China," says Vora.

China has its own set of economic challenges, too. Its zero Covid policy, crackdown on tech giants, and the stress in the property market, have roiled sentiment. The People’s Bank of China cut interest rates to nip any spillover effects from the credit crunch affecting real estate developers. This is in contrast to the monetary policy stance of global economies that are tightening liquidity.

![]()

“I believe India is a consensus overweight in the emerging market space among sell-side research houses. This is partly because China has visibility problems–the impact of the ‘Common Prosperity’ programme on earnings, and the problems in the property market. Meanwhile, India has a young population, a digital economy that’s still in its infancy, and stable politics," says Matthews.

Intriguingly, at a time when India is reeling under the impact of huge FII outflows, China has seen foreign investors pump in close to $19 billion in January, according to EPFR and a Kotak Institutional Equities report dated February 25.

“The Chinese markets have been underperforming for some time now, so some amount of relative value buying has emerged for Chinese equities. So, while India saw outflows, China has seen significant inflows in the last 12 months. Given the size of the Chinese markets, the absolute numbers are significantly bigger than what we would see for India," Vora explains.

Though some pockets of India stocks are relatively more expensive in comparison to peers, investors are divided on returns, given the recent outperformance of Indian equities.

“I think India is one of the better performing emerging markets and investors have been seeing good gains they wouldn’t have seen in China or Russia [for example]," says Holland.

In line with the slew of sanctions on Russia following its unprovoked military aggression in Ukraine, the MSCI and FTSE Russell have said they will remove Russian equities at zero value from all global and regional indices. However, this is unlikely to meaningfully divert FII flows into India or other emerging markets.

![]()

“MSCI will now call Russia as a standalone market. MSCI standalone market indices are not included in any of the widely followed passive indices like the MSCI Emerging Markets Index or the MSCI Frontier Markets Index, missing out on foreign passive flows," says Abhilash Pagaria, head, Edelweiss Alternative Research.

Other countries in the standalone category include Botswana, Lebanon, Palestine, Panama and Zimbabwe.

Eye on ETFs

Exchange- traded funds (ETFs) have been high on the radar of foreign investors betting on emerging markets compared to actively managed or country dedicated funds.

“We have seen a trend of country-specific funds losing favour, and most of the flows are in global funds or emerging market funds that are funds with a wider mandate. India-dedicated funds have been losing favour," says Vora.

For example, in the last calendar year, over 90 percent of FII flows came in via ETFs, according to the Kotak Institutional Equities report quoted earlier. In effect, the recent FII exodus, may then not necessarily be directly linked to India losing sheen as an attractive market for foreign investors.

“FIIs were underweight on China, but since India became expensive and the fund size is increasing, they are allocating more towards China," says Vora.

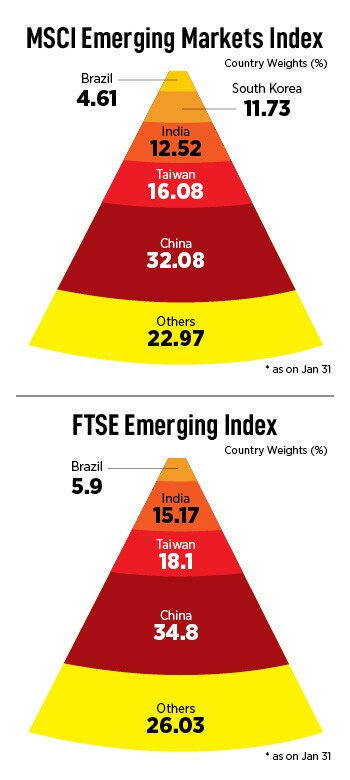

India and China roughly comprise around half the country allocations in most emerging market indices (see chart). China has the maximum weightage in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index and FTSE Emerging Index at 32.08 percent and 34.8 percent respectively.

In January, India dedicated funds saw outflows of $101 million, of which over 95 percent were via non-ETFs, while Global Emerging Market (GEM) funds recorded inflows of $898 million, and nearly half of this was from ETFs, says the Kotak Institutional Equities report mentioned earlier.

“Allocations to India by Asia ex-Japan funds declined marginally to 16.3 percent in January from 16.4 percent in December, while allocations to India by GEM funds increased to 13.4 percent in January from 13.3 percent in December," it adds.

DIIs: Last man standing?

The resilience of domestic investors has held the market together in the past few months (see table). Despite FIIs pulling out at a furious pace, there has, undoubtedly, been a correction from the top, but markets have not crashed.

![]() Though FIIs own one-fifth of the shares of companies listed on the NSE, they seem to have less sway over Dalal Street now than in the past, given the hectic activity of domestic investors.

Though FIIs own one-fifth of the shares of companies listed on the NSE, they seem to have less sway over Dalal Street now than in the past, given the hectic activity of domestic investors.

Household savings, the lack of other investable options, and low interest rates have driven retail investors to stock markets like never before. From 40 million demat accounts in March 2021, the number has more than doubled in nine months.

“Foreign investors continue to sell in the market but that’s more of a global risk-off trade rather than India-focussed trade," Holland says.

Frontline stocks in the IT and financial services space have borne the brunt of the FII selling in the last one month. FIIs are selling in the cash market and index futures, indicating that FIIs see more downside risks, and the sentiment does not show signs of reversal in the near term. However, as investors scout for returns in an increasingly volatile world, India is likely to benefit.

“I suspect FIIs will be buyers, especially as money will need to be re-allocated from China and Russia. Also, Taiwan and South Korea are the two largest emerging markets after China. There is increasingly a sense that the technology sector will not be the market leader in the next few years, so money could be re-allocated away from them too," says Matthews.

Yet, foreign direct investments (see chart) and inflows into the primary market have been strong (see chart). “If you look at the long term, global investors have always been positive for India. In the last 25 years, there have only been three years in which foreigners have been net sellers. Moreover, India has always been an overweight position for global portfolios," adds Vora.

A rate hike in the US can potentially drain out liquidity and stem inflows into financial markets. Also, higher rates in the US may skew the risk-reward ratio against most emerging markets, making them relatively less attractive for FIIs as they increase investments in developed markets.

A rate hike in the US can potentially drain out liquidity and stem inflows into financial markets. Also, higher rates in the US may skew the risk-reward ratio against most emerging markets, making them relatively less attractive for FIIs as they increase investments in developed markets.

Though FIIs own one-fifth of the shares of companies listed on the NSE, they seem to have less sway over Dalal Street now than in the past, given the hectic activity of domestic investors.

Though FIIs own one-fifth of the shares of companies listed on the NSE, they seem to have less sway over Dalal Street now than in the past, given the hectic activity of domestic investors.