Tech & small towns: StanChart's India game plan?

Unlike rival Citibank, Standard Chartered Bank has the option to explore retail banking more aggressively. Backed by a digital thrust, CEO Zarin Daruwala has more opportunities than challenges ahead o

Image: Debajyoti Chakraborty/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Image: Debajyoti Chakraborty/NurPhoto via Getty Images

When Citibank announced, on April 15, the shuttering of its consumer banking business across several countries, including India and China, the glaring reality surfaced—once again—that the preferences which foreign banks once enjoyed in India in the retail banking space have completely vanished.

Over the past two decades, the massive domination that Indian private banks such as HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank have come to command in retail, has led foreign banks to lose their premium position.

Citi’s exit has also meant that Standard Chartered Bank, which has 100 branches in 43 cities, and operating here since 1858, will need to start to dominate the consumer banking position once again. StanChart offers a mix of retail products, from personal and home loans to loans against securities and property and credit and debit card products to its Indian customers.

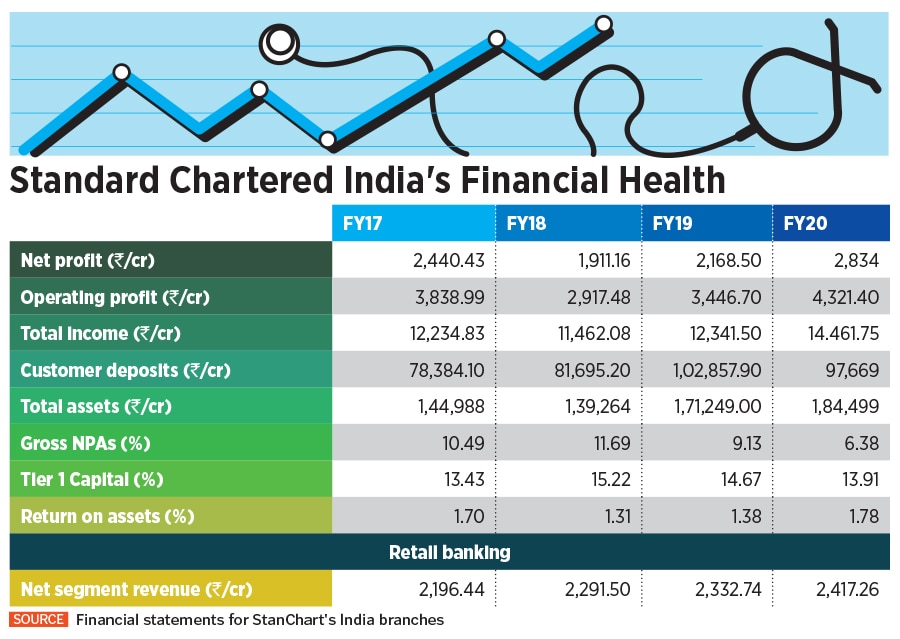

Standard Chartered Bank’s tryst with retail banking in India has been mixed in many ways. Over the past decade, its retail banking size as a percentage of the total business has ranged between 24 and 30 percent. In FY20, the Indian operation reported a net segment revenue of Rs 2,417.26 crore for retail banking and Rs 3,637.8 crore for wholesale, from the total of Rs 9,420.76 crore.

The bank’s focus on retail has always been steady and well measured, without getting too aggressive. It is something that rivals and bank insiders might want to say about the tenure of its chief executive Zarin Daruwala too.

Daruwala joined StanChart in April 2016 as its first India woman chief executive, knowing fully well that she needed to turn around a few things at the bank. Its then balance sheet size (of around Rs 132,000 crore) had not grown rapidly for the previous three years. Daruwala took charge just after StanChart had reported in FY16 a high gross NPA ratio of 14.1 percent (from 8.9 percent a year earlier), hurt by legacy high exposure to old-world infrastructure and energy projects.

While StanChart has—in recent years—recovered a portion of money lent in previous years to Essar Steel through NCLT resolutions, Daruwala needed to ensure a further de-risking of the business by focusing beyond wholesale banking.

The boost was given to retail banking and it embraced digital technology to attract millennial clients. The difficult part was breaking a perception. Daruwala, with a strong CV of having led wholesale banking business at private lender ICICI Bank, had never been known as a retail banker.

Retail banking involved rebuilding processes, teams and vision. “Targets were reset, pricing strategies fine-tuned, physical infrastructure optimised and sales channels re-organised. The bank expanded the balance sheet growth through portfolio purchases and wealth product expansion," says Daruwala, after Citibank’s recent exit. Zarin Daruwala, CEO at Standard Chartered Bank, India

Zarin Daruwala, CEO at Standard Chartered Bank, India

Focus on technology

Prior to the expansion of private sector banks and their digital drivers, starting in the mid-1990s to about 2005, foreign banks were seen to possess superior technologies compared to Indian private and government-owned banks. This was to change dramatically with the expansion of fintech startups, and the adoption of digital technologies and artificial intelligence by lenders such as ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank, State Bank of India and Yes Bank.

Foreign banks like StanChart had no option but to take rapid steps between 2018 and 2020. “Even prior to the pandemic, we moved to source business through digital platforms, which ensured business momentum through last year’s lockdown. Technology was used to provide a 360-degree view of the borrower’s ecosystem," says Daruwala. Last May, the bank launched a service that allowed clients to direct all their service requests through mobile banking, meaning zero visits to the bank or even calls to the bank’s contact centres for servicing needs.

A full refresh was carried out to sharpen product features—across secured and unsecured lending businesses—with a new marketing campaign #Techiteasy, launched by the bank’s brand ambassador actor Anushka Sharma, to support the bank’s video KYC and virtual credit cards launches. “This included scaling up of digital capabilities, including paperless onboarding of clients and open architecture wealth platforms," Daruwala says. How adaptive StanChart is to digital banking will be a game changer for the bank.

Last week, the bank’s chief financial officer Andy Halford—while announcing first quarter earnings—said that they would reduce their network from 776 branches to 400, a move seen over the past four to five years, but hurried by mobile and online banking and now the pandemic. About 13 percent of StanChart’s branches are in India.

From this January, at a global level, the bank has merged its retail banking and private banking segments into a single consumer, private and business banking segment. Corporate, commercial and institutional banking will be the second re-organised segment.

Small-town opportunities

In calendar year 2020, the India operations of StanChart reported a fourfold jump in profit before tax at Rs 2,527 crore ($337 million) against Rs 592 crore ($79 million) in 2019, led by a 16.3 percent rise in income at around Rs 9,337 crore ($1,245 million).

Retail banking was often seen as a source of low-cost deposits for banks. But today the competitive strength of a bank is judged by the products it offers and the reach it has in consumer banking.

During the pandemic, market uncertainties have increased, where irregularities of income and job security are a constant, which has made it challenging to lend to the micro-finance and unsecured personal loans segment. Fitch Ratings expects a moderately worse environment for the Indian banking sector in 2021, with micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and retail loans to be most at risk.

India’s largest private lenders have reported weak growth in their retail loan books in the March-ended quarter just gone. HDFC Bank, in its March 2021-ended quarter, reported a 4.49 percent rise in domestic retail loans while gross NPAs were at 1.32 percent as a percentage of gross advances, against 1.38 percent (proforma) as of December 2020. ICICI Bank reported a 7 percent jump in its retail loan portfolio in the same March-end quarter, with gross NPAs at 4.96 percent in the same period, compared to 4.38 percent in the December 2020-ended quarter.

Retail loans might see increased stress if pandemic-related restrictions become more stringent and hurt individual incomes and savings, say analysts. Banks will also need to boost their provisioning towards stressed assets. But they are hopeful that the impact on collections and delinquencies will be lower than last year, as the lockdown restrictions have so far been less severe.

India’s large private sector banks HDFC Bank, ICICI, Bank and Axis Bank and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) like Bajaj Finance and Mahindra Finance have realised the need to find new retail clients in tier 4,5 and 6 towns, and devise new products specifically for them, in order to keep growing. This only comes through a sound understanding of the local market environment. “This was not available at foreign banks," says Ashvin Parekh, managing partner of Ashvin Parekh Advisory Services (APAS).

It remains to be seen whether StanChart is willing to explore such opportunities beyond the metros to make its retail presence, which is a mix of servicing small businesses and individuals, meaningful.

“We entered the pandemic on a strong footing, having built a robust platform based on steady liquidity and low impairments," says Daruwala. “We will continue to focus on funding asset growth through long tenor [duration loans] and strategic, statutory efficient liabilities."

Short-term uncomfortable concerns

Experts say Citibank’s exit in consumer banking in India does not directly throw up any fresh opportunities for StanChart or HSBC. If they were there, these would already have been explored. Despite a tough banking environment, HSBC’s India business hasn’t shown any cracks and it is likely to focus more on its commercial banking and global banking and markets (transaction banking, investment banking, advisory and forex) divisions, which were profitable in 2020.

While the bidding for Citibank India’s consumer banking portfolio will gather pace in May—and StanChart cannot be ignored as a potential bidder, although they have not commented on the possibility—there are uncomfortable questions that are being raised after Citibank’s move to exit from consumer banking in 13 nations. “For a foreign bank, the financial performance [in one market] is relative to the rest of the world," says a former Citibank employee, on condition of anonymity.

So, the longer India takes to come out of the pandemic’s second wave, internal ratios for various foreign banks operating in India run the risk of appearing weaker than other markets of the West. It is also clear that, if in a country, a particular foreign bank is not among the top banks, or if that country is not its ‘core’ market, investing capital at this stage will always be a risky proposition.

Analysts and investors are likely to question whether other banks might do what Citibank did. The exception to the rule is a bank such as Singapore-based DBS, which identifies India as one of its six ‘core’ markets and has, accordingly, made strategic decisions by expanding its retail presence organically and inorganically.

Balance sheet concerns aside, marketing budgets for some foreign banks are also the first to shrink if the pandemic sustains.

A few days after Citibank’s decision, South Africa’s second largest bank FirstRand Bank announced its intention to scale back its presence in India by converting its branch to a representative office.

APAS’s Parekh, however, dismisses the global concerns issue. “Foreign banks go through these kinds of evaluations on a regular basis," he says. The decision for a foreign bank to invest capital in a pandemic-hurt economy appears to be a short-term concern rather than a long-term one.

As the Covid vaccination drive strengthens, and the threat to human life and pressures on the health care infrastructure subsides, India appears best placed to offer steady economic growth and lending opportunities. Global investment banks have downgraded their FY22 economic growth projections for India, but it still hovers at an impressive 10 percent for the full financial year.

For the time being, Daruwala has more opportunities than challenges on her hands. The fact that she is astute and rarely in a hurry means that if she finds retail banking turning into an expensive proposition, she will work out a method of getting there and yet keep her costs under control.

The critical issue for a foreign bank, at least in retail, is to stay nimble and be able to take decisions based on the local conditions, such as understanding income pressures, how much and when to push credit and when not to. These are local region decisions and not headquartered activities.

First Published: May 04, 2021, 12:20

Subscribe Now