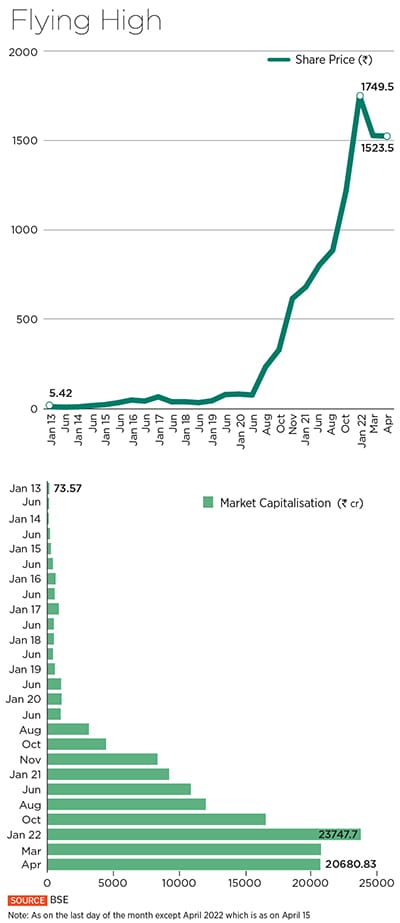

Hyderabad-based Tanla Platforms, a CPaaS (Communications Platform as a Service) company, offers wireless data services for mobile messaging. It saw its shares double during a spectacular rally on the bourses last year. In fact, since March 2014, its share price has grown a staggering 38,000 percent, which means that an investment of ₹1 lakh in the company, would have grown to ₹3.8 crore in eight years.

Tanla currently has a market capitalisation of ₹20,680 crore and is among the few Indian companies that have made massive inroads into the CPaaS space. Over the past two decades, since it first began operations, it has changed its business model a few times before finding success in the Application-to-Person (A2P) messaging business in the past few years.

“I was very clear from day one that I wanted to be in business," says Reddy from his Hyderabad office that is lined with numerous autobiographies and self-help books. Reddy wakes up at 4 am and spends about half an hour in bed to talk to himself, find solutions to problems, and even find new challenges to solve. He’s a teetotaller, spends nearly two hours at the gym, abstains from eating non-vegetarian food and is often in bed by 8 pm. “My best friend is a clerk at a bank," he adds. “I don’t socialise… I spend much of my time on building the business. I am here for the long haul."

It’s this steadfast focus and determination to build a business, and in the process his own legacy, that brought Reddy from a village in Khammam, Andhra Pradesh, after being wronged by his family, to where he is. He’s grown Tanla into a business that processes over 169 billion messages per year and has a market share of 40 percent in the category.

According to brokerage firm HDFC Securities, 1.2 billion commercial SMSes are sent in India every day. Tanla handles 169 billion messages annually or 0.5 billion per day. With 750 million active smartphone users in the country, that translates to roughly two messages per day per mobile phone user, of which Tanla now processes one message a day.

Master of his fate

Reddy was born into a wealthy family in Khammam. “In my second grade, my mother wrote on the calendar that her son was going to become a businessman," says Reddy, who grew up in a joint family that underwent separation and subsequently a division of assets. “I was curious what we were getting during the division," he says. “I recall each conversation I had with my mother… I wondered why we were not getting the better assets."

![]() His father, a soft-spoken man, was kept away from the lucrative contract business, which largely involved the construction of roads and buildings, and was instead handed agricultural land by his grandfather. “I told him what you’re doing is not fair," Reddy recalls telling his grandfather as a 10-year-old. “He said your father cannot handle it. I said fair enough, but maybe I can handle it. He told me that I was too young, but I said we will grow one day."

His father, a soft-spoken man, was kept away from the lucrative contract business, which largely involved the construction of roads and buildings, and was instead handed agricultural land by his grandfather. “I told him what you’re doing is not fair," Reddy recalls telling his grandfather as a 10-year-old. “He said your father cannot handle it. I said fair enough, but maybe I can handle it. He told me that I was too young, but I said we will grow one day."

That feeling of wrongdoing stuck with him. He was desperate to prove his mettle. By the time he was in class 9, his sister, who had recently got married, moved to Hyderabad. Reddy followed her into the big city to stay with her. “The desire to be in business continued and I enrolled for a bachelor’s degree in commerce," he says. After completing his degree, Reddy began preparing to do chartered accountancy. “I realised that my bosses were only interested in helping many evade taxes," he says. At the same time, he realised the nitty-gritty of running a business after meeting numerous businessmen during his articleship. Around the same time, his brother, a journalist, was allotted land by the government in Hyderabad’s Jubilee Hills—then barren land and now one of the most expensive addresses—much before the real estate boom.

“My brother-in-law was trying to build a house," Reddy says. “When we moved there, my curiosity doubled and I began to question why the area was important because there were just four houses, and people used to come to buy land. Everybody wanted to buy land there." That’s when he was introduced to the world of real estate. But Reddy also understood that while the business was lucrative, it was disorganised and documentation was missing in most cases. His exposure to chartered accountancy meant he understood the importance of paperwork.

“I knew I wanted to get into real estate, but I didn’t have the money," says Reddy. He met with a distant relative and sought ₹2 lakh from him. “He probably saw some fire in me. I told him I would repay him in two months," he recalls. With ₹2 lakh as capital, Reddy bought a plot of land and ensured that the documentation was in place. “In those days, there was so much doubt and concern about documentation and papers. There was a lot of manipulation with survey numbers," says Reddy. “I worked on the paperwork for three days, went to the registration office and other government offices, built a file, and ensured that the paperwork was proper." Within five days, he sold the plot, making a profit of ₹2 lakh.

Thus began Reddy’s tryst with real estate. Over the next few years, Reddy bought and sold numerous properties, and by the mid-’90s, he was paying some ₹5 crore in taxes. “When something is working in your favour, you cannot slow down," says Reddy. “I used to work for 15 to 16 hours a day and sleep for just three or four hours." Much of the business involved identifying barren land that people made into plots—without adequate documentation—and were struggling to sell. Reddy would buy them, and do the necessary paperwork before making a killing from the sale. Coincidentally, it was a time when Hyderabad was slowly turning into an IT hub.

In 1996, Reddy enrolled for an MBA at the Manchester Business School, but would fly down every weekend to India for his real estate dealings. “It was very tiring, but I didn’t care about it," says Reddy. “Because I didn’t want to miss the opportunity here. I wanted to have a connection with my buyers and sellers." By the time he finished college, Reddy wanted to move from real estate into technology, although he was uncertain about what to do. “I wasn’t enjoying real estate, and I had made enough money," Reddy says.

Tryst with Technology

In June 1999, Reddy started Tanla Platforms though he didn’t have a clear plan on what the business would do. The name was a mix of his wife’s (Tanuja) and a relative’s (Nila) names. The latter had joined the business briefly.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into," says Reddy. “But my confidence was high." Over the next few months, he set up an office and went there regularly even though he had no business to show. “After some time, I grew frustrated," he recalls. That’s when he realised that the telecom sector in India was in for a big shake-up, especially with mobile phones gathering steam. “As part of my project during my MBA, I worked with Vodafone for a month," says Reddy. “In business school, we used to send SMSes (short message service) to our friends. When I came to India, nobody was using text. This is what I identified as the next opportunity."

![]() Reddy then met up with some friends who connected him to someone who could help him build his telecom business. “They said you are a weird guy, we know another weird guy. Why don’t you’ll get together?" he says. Soon, he met Sirish, a school dropout, who partnered with Reddy after much persuasion.

Reddy then met up with some friends who connected him to someone who could help him build his telecom business. “They said you are a weird guy, we know another weird guy. Why don’t you’ll get together?" he says. Soon, he met Sirish, a school dropout, who partnered with Reddy after much persuasion.

Within 20 days, Reddy built Tanla’s first SMSC (Short Message Service Centre) which helps store, forward, convert and deliver SMSes. “It sits as part of the telecom network and enables communication between two players," says Reddy. “At that time, people were focussed on the voice network and no telecom player had its own in-house SMSC. Nobody bothered about SMS then."

Tanla then partnered with Jaipur-based Hexacom, a subsidiary of Bharti Airtel, and deployed its service, which Reddy says found phenomenal success in two months. Tanla was also the first Indian company to have successfully built and deployed an SMSC, which meant that it grew to about 70 people by 2004.

In 2005, Tanla purchased Smartnet Communication Systems, a software development company based in New Delhi, and the company’s SMSC had already been deployed with Reliance Telecom, BPL, Airtel, Aircel and Hutch. “We were growing like mad," Reddy says.

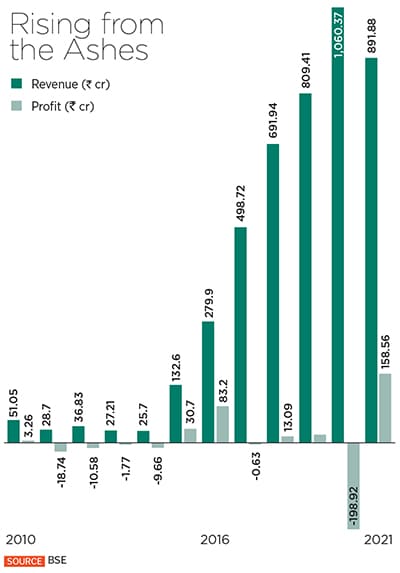

In 2006, Reddy took the company public and by 2007, the company’s revenue grew to ₹230 crore.

“From the IPO, we had generated enough money and were cash-rich," says Reddy. In 2008, he took one of the biggest gambles of his life, when Tanla decided to acquire Openbit OY, a Finland-based company that specialised in services such as maps and on-device payment solutions for companies like Nokia and BlackBerry in addition to servicing 3D Arts and F-Secure, and other similar companies. The company had some 40 patents and was known to provide embedded solutions in over 20 million handsets manufactured by Nokia, Samsung and BlackBerry. “They were more into the handset side while we were on the telecom side," Reddy says. “We acquired them for ₹260 crore… they were growing by leaps and bounds. They were the primary software vendors for both Nokia and BlackBerry."

However, within the next two years, after Samsung and Apple disrupted the market by bringing out smartphones, Nokia and BlackBerry were among the hardest hit. By 2011, Tanla too saw a massive crash in its wealth since much of its business was focussed on Nokia and BlackBerry. “Nokia didn’t have app stores," Reddy says. “A smartphone is capable of handling applications."

Tanla’s Finnish business would help install apps such as maps (owned by Navteq) into the devices at a time when maps weren’t easily available on smartphones. But as smartphones changed the dynamics of the business, and apps were free to download, companies such as Apple and Samsung killed companies such as Nokia and BlackBerry. Tanla, too, was in trouble.

“From a billion-dollar company, we fell to ₹25 crore," says Reddy. By 2012, Tanla’s share price fell to ₹2 and its revenues fell to ₹37 crore, while losses mounted to ₹10 crore.

Rebuilding Tanla

Between 2010 and 2014, Reddy’s business was in murky waters. Revenue had dried up and was a fraction of what it had been in the preceding years, even as losses continued to balloon. “In hindsight, where we went wrong was that we forgot about our primary business which was communications," he says. “We opened an office in London, South Africa, and kept selling services on mobile."

Thankfully, Reddy had partnered with some friends to set up a real estate venture in 2002, and that business was flourishing then. Even then, he had to let go of over 1,000 people before finding a way back into the business. “I had two options," Reddy says. “One was to close down the business. The other was the opportunity for me to bounce back. We had enough cash on the books."

Over the next three years, Reddy began cleaning up the mess, shutting down all global offices, and by 2014, he was focusing on its primary business. “That business still had the potential to grow," he says. “I was personally very rich. But I couldn’t let Tanla struggle. I had to swallow my ego and wait for three days for a meeting with Vodafone outside their office." In 2014, Tanla tied up with Vodafone to deploy its A2P messaging platform which featured advanced security, reliability, analytics, and service levels, along with what it called a proven ability to process the largest volume of messages per second.

“We realised that companies needed to communicate with the users and vice versa," says Reddy. “For example, people started using one-time passwords or debit alerts. That’s where we identified our opportunity to strike again." Over time, once the deal with Vodafone began to show results, Tanla started partnering with other telecom operators. By October 2015, Tanla’s A2P platform processed more than 5 billion messages a month and set a record of processing over 200 million messages in a single day, making it the world’s largest A2P messaging platform by volume of messages.

“We have really built the business with Vodafone," says Reddy. “After that, every telecom company said these guys are very serious partners and would like to partner." In addition to Vodafone, Reddy had on-boarded Airtel and Idea. Even then, the turmoil of the previous decade continued to haunt him.

“I told my guys that we’re concentrating on only three companies and there is a lot of risk in that," recalls Reddy. “That’s where we went wrong last time. We can’t make the same mistake again." It was also a time when Reliance Jio had just entered the Indian market, and the telecom sector was in for a serious shake-up after Jio offered cheaper tariffs.

That’s when Tanla stumbled upon Karix Mobile (formerly mGage India) and its wholly-owned subsidiary Unicel. Soon, with its internal accruals and 80 percent cash payments, Tanla acquired the company from GSO Capital Partners, a Blackstone firm, for ₹340 crore. “They are the ones who service most of the enterprises in India, including the government of India," says Reddy. The company specialises in A2P messaging, including chatbots, SMS, voice, and email, among others, and had some 1,500 clients across banking, insurance, retail, FMCG, social media networks, ecommerce, and government agencies.

“Whenever companies want to communicate with their users," Reddy says, “Karix enables that and remains a facilitator through SMS, WhatsApp, email push notification, and the like. Tanla was mainly focusing on the telco side, while they’re focusing on the enterprise side."

With the acquisition in place, Reddy set out to strengthen his board, processes, corporate governance, and audits to ensure the organisation was ready for its next phase of growth. In 2019, Tanla acquired Hyderabad-based Gamooga, an AI-driven omnichannel marketing automation platform that enables businesses personally engage with their users across channels, including email, SMS, voice, website, apps, and other leading channels.

“The (Karix Mobile) acquisition has been a turning point in Tanla’s journey," HDFC Securities said in a recent report. “Growth in its enterprise business has been led by Karix. Karix’s revenue has grown at a 20 percent CAGR over FY16-21. We expect enterprise CAGR of 25 percent over FY21-24E, with a gross margin of 21 percent."

In 2018, the company also turned its attention toward blockchain and has now built up a blockchain-based stack to reduce the problem of spam. The stack ensures that SMS and OTPs—when sent by enterprises—are checked against the templates pre-registered by them on their blockchain platform. In 2018, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India issued draft guidelines to reduce spam in the telecom ecosystem and asked companies to turn to blockchain.

“Everybody shied away from blockchain," Reddy says. “We had never heard about it. I didn’t even know how it worked. But I told my team, that’s where our strength is, and let’s take the risk."

Within six months, Reddy claims his company built a platform, which has since brought it global attention. “Tanla has tasted success with the launch of Trubloq, a blockchain-based platform deployed with major telcos, and processes 63 percent of India’s A2P messaging traffic," HDFC Securities says.

Today, about 45 percent of the company’s revenue comes from global sources, while the remaining is generated in India. It counts Google, Facebook and Microsoft among its clients. A recent study by research and advisory firm Gartner estimates that by 2023, 90 percent of global enterprises will rely on CPaaS offerings to enhance their digital competitiveness, up from 20 percent in 2020.

According to a UK-based consultancy firm Juniper Research report, the worldwide CPaaS market would increase at 29 percent CAGR between 2020 and 2025. That means, the global revenue of 12 publicly traded CPaaS communication providers is expected to grow to $27.4 billion by 2026 from $8.7 billion currently. All that has meant that institutional investors, including the likes of MIT Endowment Fund, Vanguard, American Emerging Fund and Premji Invest, tech billionaire Azim Premji’s private equity firm, have flocked to Tanla Platforms. In February, Tanla announced a partnership with Truecaller to help Indian businesses deliver messages with rich media content, in an attempt to take on WhatsApp for business service.

Which means Reddy is back on a firm footing. And this time, he is shielding himself from any distractions. “The minute you are in your comfort zone, you are out of the game," says Reddy. “I would like to go to sleep with problems. I must have enough problems for me to find solutions. There is a sense of purpose now."

His father, a soft-spoken man, was kept away from the lucrative contract business, which largely involved the construction of roads and buildings, and was instead handed agricultural land by his grandfather. “I told him what you’re doing is not fair," Reddy recalls telling his grandfather as a 10-year-old. “He said your father cannot handle it. I said fair enough, but maybe I can handle it. He told me that I was too young, but I said we will grow one day."

His father, a soft-spoken man, was kept away from the lucrative contract business, which largely involved the construction of roads and buildings, and was instead handed agricultural land by his grandfather. “I told him what you’re doing is not fair," Reddy recalls telling his grandfather as a 10-year-old. “He said your father cannot handle it. I said fair enough, but maybe I can handle it. He told me that I was too young, but I said we will grow one day." Reddy then met up with some friends who connected him to someone who could help him build his

Reddy then met up with some friends who connected him to someone who could help him build his