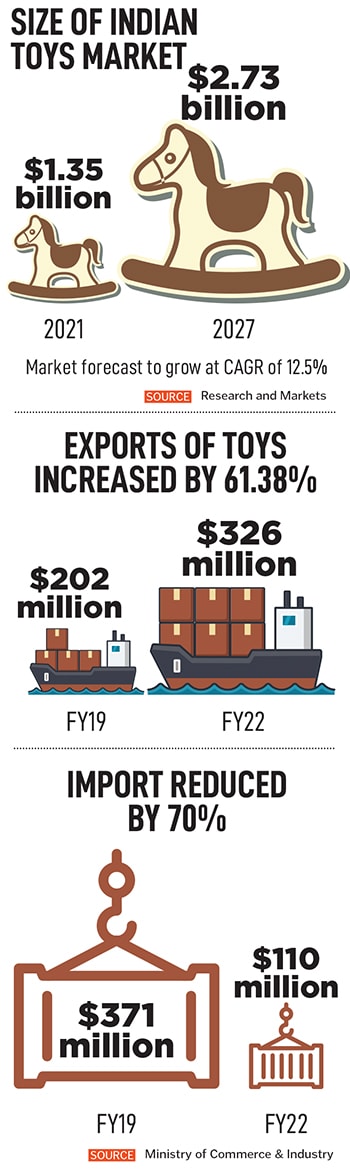

Exports of Indian toys are at $326.63 million for FY22, up from $96.17 million in FY15, said Bhanu Pratap Singh Verma, Union minister of state for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME), in a written reply to the Lok Sabha. Toy imports fell to $109.72 million in 2021-22 from $332.55 million in 2014-15.

Currently, the toy sector is highly fragmented, with only a handful of large players, and multiple SMEs and MSMEs. This is expected to change soon. The government, as per media reports, plans to launch a ₹3,500-crore production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for Indian toy manufacturers. This scheme will be for finished toys—and not toy components—that comply with Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) norms.

The PLI scheme will help in developing an ecosystem for the toy manufacturing sector, to make quality toys for domestic and global markets. “With PLI, some of the bigger units will come out of India, and those bigger units will help India establish or build the smaller MSME sector also, because they will be able to create that ancillary support as well," says Manu Gupta, chairman, Toy Association of India, and chairman, Playgro Toys Group. The company started as a retailer and then moved into large-scale manufacturing of toys. Currently, it does third-party manufacturing and sells via its own brand in the domestic market. A minuscule percent of its total revenue comes from exports.

Setting up good manufacturers for ancillary industries such as packaging, plastic pipes etc is equally important. Akshay Jalan, co-founder, AllThingsBaby, and wooden toys brand Brainsmith, says, “For some of our products like the Shape Sorting Clock, we need plastic arms for the clock. We see that the ones available in India aren’t of great quality. So we have no choice but to source it from China. To prevent this, we need the ancillary industries to grow as well, so we no longer need to depend on China or other countries. This is where the PLI scheme will be extremely useful." Jalan claims that one company—at least when it comes to wooden toys—has to work with a minimum of 20-30 suppliers for different kinds of raw materials.

But the PLI scheme is likely to only be for toys, and not toy components. Isn’t that a disadvantage? “The toy industry doesn’t have any standardised components like one has in electronics. There is a huge variety when it comes to toys, and it also depends on seasonality (outdoor toys would sell more in summer, for example). It is impossible to give a PLI for toy components," explains Amit Chakraborty, president of the toys division, Aequs, one of the largest toy exporters in the country.

The Toy Association of India and a few large players have been working closely with the government and have suggested a few recommendations. The first is that all toys, regardless of their functionality or raw materials, should be included in the scheme. Gupta says, “Some of the other sectors have extremely stringent pre-eligibility norms for the scheme, which we hope won’t be the case with toys."

Level-Playing Field

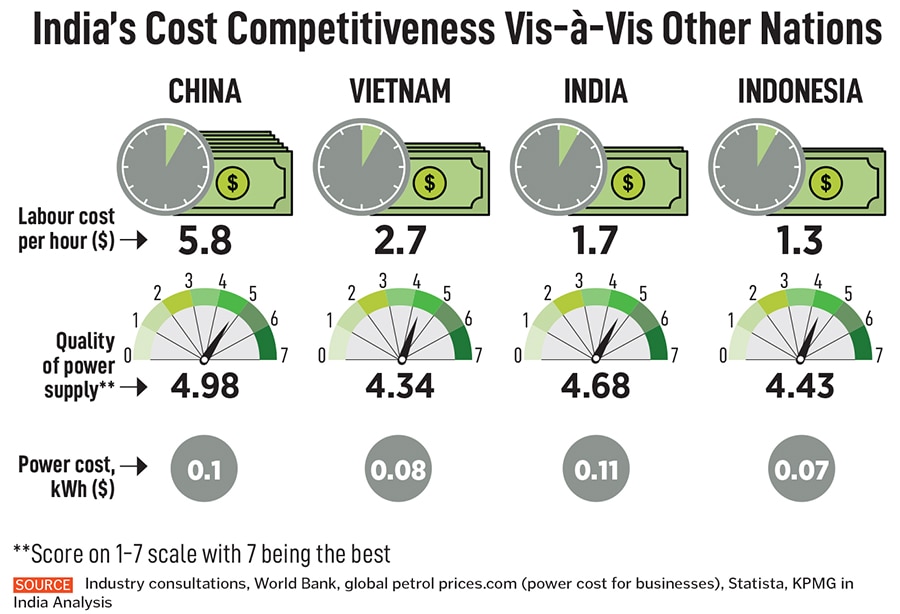

The world is looking for a China-plus-one model, and while Vietnam, Indonesia and Mexico are strong competitors, India has an advantage of cheap labour. “In February 2020, the government increased import duty to 60 percent, which was 34 percent earlier. This has helped in reducing imports, since China has over-subsidised its toys," says Gupta.

![]()

Additionally, in January 2021, the Quality Control Order was implemented, which mandated toys to have a standards-compliance mark (ISI) under the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). The BIS ensures quality consciousness among manufacturers, industry, consumers and government departments.

“These safety regulations ensured that the unregulated imports of unsafe toys were kept under check," says Gupta. So far, the BIS has granted 1,001 licences to domestic manufacturers and 28 licences to foreign manufacturers for toys with BIS standard marks. Before the BIS certification was implemented, says Jalan, “There was a time when China would dump low-quality toys that were mostly found to be unsafe for children. The certification has created a stringent barrier that has disabled the influx of such low-quality toys within the country to a large extent, through the new certification mechanism."

While imports have dropped, exports have increased—a good sign for Indian toymakers. Chakraborty agrees, “For large toy manufacturers, targeting the domestic market is not good enough to grow. Exports are necessary to capture the global market as the domestic market is relatively small."

To attract more international buyers, and further increase exports, a National Action Plan for Toys 2020 was introduced to promote the Indian toy industry, including traditional handicrafts and handmade toys. The government wants to make India a global toy hub.

Post the Toycathon and Toy Fair in 2021, the Khilona 2022—India Toys & Games Fair took place in August 2022 and saw close to 11,000 visitors and 12 international players, according to news reports. Industry players reckon such toy fairs need to keep going, and grow in scale, as they are the best way to attract foreign buyers.

![]() Workers put together a toy on the final assembly line at an Aequs manufacturing unit in Belagavi, Karnataka. Aequs, one of the largest toy exporters in India, has set up operations in one of the largest SEZs being set up in Koppal in the state Image: Courtesy: Aequs

Workers put together a toy on the final assembly line at an Aequs manufacturing unit in Belagavi, Karnataka. Aequs, one of the largest toy exporters in India, has set up operations in one of the largest SEZs being set up in Koppal in the state Image: Courtesy: Aequs

The government is also encouraging the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and toy clusters across India—which will help organise the disorganised industry. “They are easing out the availability of critical components and helping us further develop toy clusters across states like Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Karnataka," adds Gupta. These will help add value for the market.

Nineteen toy clusters have been approved, benefiting 11,749 artisans with an outlay of ₹55.65 crore. According to the India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), Maharashtra leads the Indian toy and game exports the exports grew to $76.3 million in 2019–20 from $32.9 million in 2017–18. Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka are other key states, with toy and games exports valued at $49.4 million and $36.4 million, respectively.

One of the largest SEZs is being set up in Koppal, Karnataka, where Aequs has set up operations and many other components and toy manufacturers have shown interest in setting up their base. The biggest advantage of setting up an SEZ is, attracting more employment. Once fully operational, we are likely to have 20,000 direct employees and 25,000 indirect employees. As we see more players setting up in Koppal, employment will further go up," says Chakraborty. His vision is to create an entire town where everything required for toy manufacturing is located in and around the ecosystem.

Though many favour the idea of setting up these clusters, Babu feels otherwise. “I believe you need to scale first before developing clusters. These will not bring scale to you. There are only four to five large players in India. In China, there are thousands of suppliers. This needs to change."

Long Way to Go

India is still not at the same level-playing field as China or Vietnam. “For starters, these countries get a lot of subsidies—about 30 to 40 percent—and support from the government. It is impossible for us to be that competitive," explains, Vijendra Babu, managing director of manufacturing company Micro Plastics, one of the largest toy exporters in India.

![]() The company started its toy division about six years ago, when Hasbro first came to India. They have six plants only for toys in and around Bengaluru with about 1.2 million square feet of manufacturing space. Even though manufacturers are looking for a China-plus-one, he adds, “Eventually, it is price which decides everything, despite all the issues the world might have with China. PLI and the various other government initiatives are a great start, but a lot more needs to change"

The company started its toy division about six years ago, when Hasbro first came to India. They have six plants only for toys in and around Bengaluru with about 1.2 million square feet of manufacturing space. Even though manufacturers are looking for a China-plus-one, he adds, “Eventually, it is price which decides everything, despite all the issues the world might have with China. PLI and the various other government initiatives are a great start, but a lot more needs to change"

One of the biggest challenges is lack of talent. “We have a lot of engineers, but they are specification-based. Toys need a fit-for-use approach, which means specifications aren’t given, only the function is. The turnaround time is short, since life cycles are short, and it depends on seasonality," explains Chakraborty. Industry players feel that the government needs to invest big money in training budgets for labour. “China is about 30 years ahead of us in terms of skilled manufacturing labour for the toys sector. If we were to match up to that, we need to invest," he adds.

The GST rate is also fairly high, between 12 percent and 18 percent. Electronic toys, particularly, are charged at 18 percent. Gupta says, “We have requested the government to bring down this rate to 12 percent since demand for these are very high. Also, electronic toys are not only categorised based on functionality, but also aesthetics. For instance, if a doll house has a light, it qualifies as an electronic toy, though its function is Pretend Play & Role Play." For domestic sales, GST is necessary, and as a pass on tax, it makes players uncompetitive compared to others.

The land prices in India are extremely high and it takes a lot of time to procure land. “This causes an increased lead time. If a brand wants to shift manufacturing to India from Vietnam or China, the development of land will take two to three years. Ideally, there should be ready units available," explains Gupta.

Though a majority of toy parts are now being sourced from India, there are certain electronic components that need to be imported from China or Vietnam, since they are not manufactured in India. “It will be helpful, if the government could consider a limited time based waiver of high import duties specifically for these electronic components," says Chakraborty. This will give time to local players to scale up their volumes and achieve desired quality and costs.

What Can be Done?

In the last six years, a fairly robust ecosystem for toy manufacturers has been set up in Inida. Though the overall dependency on Chinese imports has dropped, the ecosystem still lacks certain aspects. Due to the lack of level-playing field, Babu feels it is hard to attract customers to come to India. “Though labour cost in India is cheap, our transport costs are very high. The customer is only looking at the landed price, though our ex-factory prices are great… they might prefer players in other countries then."

For exports particularly, every shipment needs to get a third-party inspection done in order to ensure quality and authenticity, but the cost is borne by the customer (in this case, the global toy MNCs). So local manufacturers seek waiver in this cost, so that the MNCs continue working with Indian players and are not disincentivised by the inspection cost.

Babu explains, “Some waiver here would help. The compliances in terms of chemical, quality, ethical and technical competency for exports are all very high. People think manufacturing toys is child’s play, but it is one of the most complex forms of engineering."

Gupta adds, “The scheme will help create mass, which will get more foreign buyers to come down to India. Toys are sold in breadth, which means you need a range of items and many more players, to fulfil the buyers’ demand."

Gupta adds, “The scheme will help create mass, which will get more foreign buyers to come down to India. Toys are sold in breadth, which means you need a range of items and many more players, to fulfil the buyers’ demand."

The company started its toy division about six years ago, when Hasbro first came to India. They have six plants only for toys in and around Bengaluru with about 1.2 million square feet of manufacturing space. Even though manufacturers are looking for a China-plus-one, he adds, “Eventually, it is price which decides everything, despite all the issues the world might have with China. PLI and the various other government initiatives are a great start, but a lot more needs to change"

The company started its toy division about six years ago, when Hasbro first came to India. They have six plants only for toys in and around Bengaluru with about 1.2 million square feet of manufacturing space. Even though manufacturers are looking for a China-plus-one, he adds, “Eventually, it is price which decides everything, despite all the issues the world might have with China. PLI and the various other government initiatives are a great start, but a lot more needs to change"