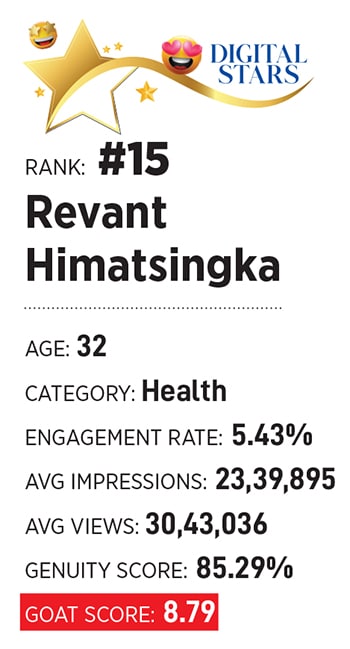

Revant Himatsingka: In a battle against junk food and false marketing

Revant Himatsingka ditched his corporate life in the US to make India watch what it eats

Last year, when Revant Himatsingka returned to India after spending a few years in the US, obsessed with the idea of making Indians aware of the perils of junk food, he had no clue what lay ahead of him. He had once published a self-help book that touched upon finance, health, religion, death and entrepreneurship, with one chapter on reading labels of packaged goods.

Back in India, after putting in his papers at consultancy firm McKinsey, Himatsingka spent a few months trying to figure out a go-to strategy before finally narrowing down on using videos as a medium to raise awareness. Finally, on April 1, the Kolkata-based Himatsingka put out a video on Bournvita, the chocolate-based children’s health drink, highlighting the amount of sugar in it. Himatsingka even went on to say the drink was preparing children for a life with diabetes instead of victory—a take on the brand’s tagline Tayyari Jeet Ki (preparing for victory).

The video went viral. Mondelēz, the makers of Bournvita, sent Himatsingka a lawsuit and asked him to withdraw the video. Himatsingka obliged, but, by then, the video was viral on WhatsApp and other social media platforms. The government soon swung into action, asking Bournvita to withdraw all misleading advertisements and in April, and asked ecommerce platforms to stop listing Bournvita as a health drink on its platforms.

For Himatsingka, though, life turned upside down with the video. He became something of a celebrity overnight and soon followed up with more videos on his page, Foodpharmer, to raise awareness on packaged content. Among his videos were those on Maggi, mango juices, airline food and ketchup, questioning their ingredients. Celebrities began sharing his videos, even though the lawsuits didn’t stop.

For Himatsingka, though, life turned upside down with the video. He became something of a celebrity overnight and soon followed up with more videos on his page, Foodpharmer, to raise awareness on packaged content. Among his videos were those on Maggi, mango juices, airline food and ketchup, questioning their ingredients. Celebrities began sharing his videos, even though the lawsuits didn’t stop.

Since then, Himatsingka has moved base to Mumbai, has one employee working with him full time and still relies on lawyers who come forward pro bono to fight out his lawsuits. The move from Kolkata to Mumbai was primarily because Himatsingka had started getting invitations to speak at various forums, and making trips frequently was becoming tedious. Plus, he says, it made sense to work out of Mumbai, India’s financial capital.

Now, apart from raising awareness and campaigns surrounding health, Himatsingka’s attention has turned to an online health school where the focus is on health literacy, in addition to running various campaigns to help create awareness. “We need to get people health-literate like the way we have been studying history, geography, integration or differentiation," Himatsingka says. “For some weird reason, we don’t have health as a subject in school. Eventually, I hope to work with various doctors and create courses around diabetes, PCOS, sleep and so on. It’s all pay what you want."

The fee for the courses, Himatsingka says, will be used to feed people. “That way, we can combat health literacy and hunger at the same time," he says. “This was something of a next step after making the videos. People were messaging me, saying we don’t know how to read the labels, and were asking me if I could teach them to read."

Click here for India’s Top 100 Digital Stars

His campaigns in the last year include Label Padhega India (India will read labels), Indian Steps Premier League, the Sugar Board movement where schools and colleges will show how much sugar is present in soft drinks, and the water bell movement.

“In schools, we are usually taught to take permission to drink water," Himatsingka says.

“It’s crazy if you think of it. Most of India is dehydrated and a lot of illnesses are born out of dehydration. For the first 18 years of our life, we’ve been told that you can only drink water occasionally and you need permission when you take a sip of water." The Water Bell movement promoted drinking water at the end of every period.

In the process, through his campaigns and the health literacy programmes, Himatsingka says, his focus is on improving preventive health care in this country, instead of therapeutic ones. “When you are young, you do whatever you want," he says. “Then when you are 45-50, you get all the diseases. That’s an unhealthy model. It’s a very big cost to the nation from an economic perspective."

“The way consumerism is going in India, with more disposable income and media awareness, it is only natural for independent stakeholders and regulators to keep a check on the model," says Harminder Sahni, the founder and managing director of Wazir Advisors, a Gurugram-based consulting firm focusing on retail and food, among others. “In the US, by far, the largest consumer market, consumer protection came about decades ago. In India’s case, if anything, it’s only a little late. Nevertheless, it is good to have such stakeholders making a case for it."

“Earlier, I relied on my savings and thought l will figure it out later," the 32-year-old says. “But now, I need to figure out sources of income." While the health school and speaking at events bring money, there is a dilemma around ethics and morality, especially as a leading social media influencer. “I am extremely confused, and this is a debatable question," Himatsingka says. “Should I promote certain things or not?"

For instance, Himatsingka had been approached to promote a mobile phone that he doesn’t use. “Technically, it’s not a conflict of interest because it’s not a health company," Himatsingka says. “It does improve cash, but people will say why is this guy, who has been going against false marketing, promoting a mobile phone company, which is probably not that great either."

While he did not take up the promotional offer finally, and the money flow remains constrained, what brings immense satisfaction are people reaching out to him to tell him about the positive impact he has had on their lives. In fact, last year, a parent had reached out, saying they had named their child after him.

So how does he look back at the one-and-a-half-year-old journey? “I can see a lot changing," Himatsingka says. “There are a lot of products now focusing on health and that is a welcome change to start. But there is a long way to go."

First Published: Oct 17, 2024, 12:02

Subscribe Now