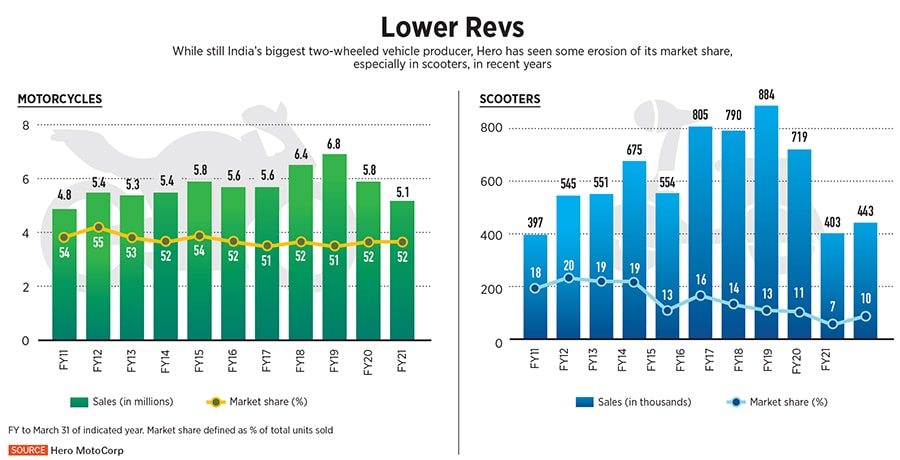

But Hero’s commanding position could be threatened by the shift to electric vehicles (EVs). While electric two-wheeled transport is still a tiny fraction of India’s market—143,837, or just 1.3 percent of total annual two-wheeled vehicle sales in the year to March—that figure has grown over four-fold in three years.

The government is also underwriting the market’s growth. It increased existing consumer subsidies on two-wheeled EV prices by 50 percent and doubled the cap on this incentive to 40 percent of the price, bringing the formerly high prices of two-wheeled EVs more in line with similar gas-powered models. In mid-September, the government announced $3.5 billion in incentives to ramp up the local production of batteries and hydrogen fuel cells. These moves are all in support of the government’s declared goal to have at least 30 percent of all new vehicles sold in India—including two-wheelers—be EVs by 2030.

The rise of EVs is one of the biggest potential threats to Hero’s decades-long market preeminence. While Hero has a history of consistently rolling out new models, it is an EV laggard—it has zero electric two-wheelers on offer. Meanwhile, over a dozen companies in India—from startups to large domestic rivals, such as Bajaj Auto and TVS Motor—now sell more than 50 different types of electric two-wheelers in India (two-wheelers are defined as mopeds, scooters and motorcycles).

![]() The iconic Hero Honda CD 100, one of the first four-stroke motorcycles sold widely in India

The iconic Hero Honda CD 100, one of the first four-stroke motorcycles sold widely in India

Image: Courtesy Hero MotoCorp

One of Munjal’s biggest competitors in the EV space is—ironically—his nephew Naveen Munjal, who runs a wholly separate company called Hero Electric Vehicles, which is now India’s market leader in electric two-wheelers by market share. With about a dozen different variants, the privately held Hero Electric last year sold over 50,000 EVs. Sohinder Gill, chief executive of Hero Electric, says the entry of a big player like Hero MotoCorp proves there is a real shift happening and that will only expand the market: “There is more than enough room for everybody to grow." Complicating matters for Hero MotoCorp is that it cannot use the brand Hero Electric on any of its EVs.

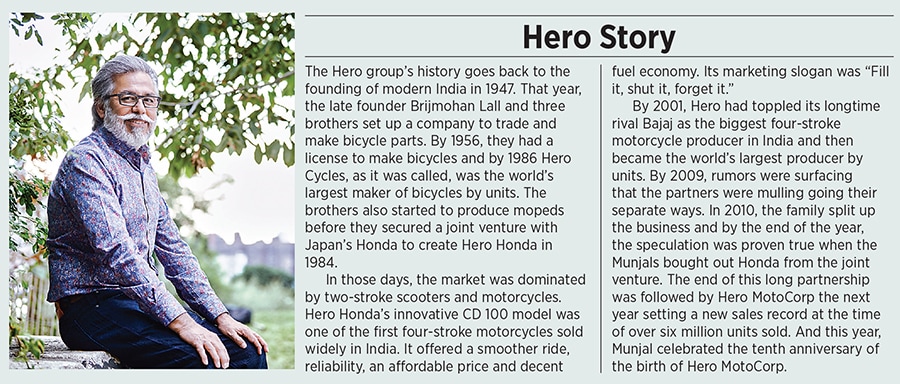

This unusual situation arises from 2010, when the Munjals split the family-owned Hero group into four. Pawan kept the crown jewel JV Hero Honda (renamed Hero MotoCorp in 2011), while Naveen’s family got the right to use Hero Electric on its company and products. Naveen claims to have been the driving force in the creation of the family’s Hero Cycles’ first electric model way back in 2001 (which was a market flop)—so he can legitimately claim to have pioneered the two-wheeled EV market in India.

![]()

Another competitor that Hero will have to contend with is Ola Electric, an offshoot of domestic ride-hailing firm Ola, which has invested $322 million to build a new factory in south India with the capacity to produce 10 million electric scooters annually. After Ola Co-founder Bhavish Aggarwal announced the launch of the Ola e-scooter on Twitter in July, the company clocked 100,000 orders within 24 hours when the bookings opened.

Hero’s plans to level the playing field rely heavily on the company’s Jaipur-based research facility, called the Global Centre of Innovation and Technology. It is here—and in a similar Hero facility in Munich—that Hero’s future in EVs hangs in the balance. The sleekly designed complex, which opened in 2016, is spread over 250 acres and houses 1,000 engineers, research facilities, an auditorium and testing grounds for regular and electric models. Solar panels on the roof help supply electricity. “We are rolling out new products, new technologies from this R&D centre," says Munjal. This facility, adds Munjal, is his “biggest, biggest pride".

![]() Hero Xtreme 160R, which has a fuel-injected engine

Hero Xtreme 160R, which has a fuel-injected engine

Coming soon, Munjal pledges, is the company’s first two-wheeled EV, a scooter, which should be ready for an unveiling by March next year. A one-minute glimpse of what appeared to be a prototype of the new scooter was shown at the company’s tenth anniversary ceremony broadcast in August from the Jaipur facility. Saved as the finale of the glitzy hour-long broadcast, Munjal tells viewers that he has a “little surprise." Without revealing any details, he stands next to a white scooter that he describes as a “bolt of lightning" and adds: “We are at the cusp of revealing this to the world."

While still tightlipped about its features, Munjal does let on during his interview with Forbes Asia that the new e-scooter will feature plug-and-charge technology. Despite being a late entrant into the two-wheeled EV market, Munjal leaves no doubt that the company’s future will be electric. “The way forward not just for us, [but] for the entire global industry is EVs, or similar technologies," he says.

![]()

The Jaipur facility demonstrates the company’s research commitment. Inside its gleaming white-clad walls one can see a motorcycle frame undergoing stress tests on a treadmill-like machine that replicates the bumpy conditions of India’s potholed roads. Nearby an engine is on a continuous 200-hour test run to check its durability, while on another platform a bike handle is being turned from side to side for 150,000 cycles to see if it malfunctions. Outside in the bright sunlight, various test tracks are designed to replicate India’s myriad road conditions, from smooth highways to rough offroad trails.

Aside from in-house research, Munjal is building Hero’s EV future through partnerships. Way back in 2016, Hero invested in Ather Energy, an Indian e-motorbike company started in 2013 by two Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia alumni. Hero now has a 35 percent stake in the firm. Hero and Ather are collaborating to develop a uniform market standard for fast chargers in India, and Hero plans to build a public charging infrastructure based on the standard. “The idea is to proliferate the infrastructure," says Munjal.

![]() The Global Centre of Innovation and Technology in Jaipur spreads over 250 acres and houses 1,000 engineers, research facilities, an auditorium and testing grounds for regular and electric models

The Global Centre of Innovation and Technology in Jaipur spreads over 250 acres and houses 1,000 engineers, research facilities, an auditorium and testing grounds for regular and electric models

Image: Courtesy Hero MotoCorp

Another early partnership to get into EVs in 2012 ended in failure. Back then, Hero took a 49 percent stake for $25 million in the US motorcycle firm Erik Buell Racing (EBR), a deal that led to the development of prototypes of two EV scooters and a hydrogen fuel-cell motorbike. However, these efforts fell by the wayside when EBR went bankrupt in 2015.

Hero’s newest partnership that was announced in April is with Taiwan’s Gogoro, one of the largest battery-swapping suppliers in the world, and which powers 97 percent of all of Taiwan’s e-scooters and e-motorbikes. Munjal has said that Hero will pursue a dual track of using both battery swapping from Gogoro and regular charging in its EVs. He says Hero’s second EV model will use Gogoro’s battery swapping technology.

![]() “The future is going to be electric, collaborative and modular," Munjal said during the tenth anniversary broadcast. One factor in Hero’s favor is its financial muscle. Armed with more than $1 billion of cash on Hero’s books at the end of March, Munjal can spend heavily to get into the EV market. The company’s overall numbers this fiscal year to March were weakened, however, by the pandemic’s impact, as net profit fell 20 percent to 29 billion rupees on a 6 percent revenue growth to 315 billion rupees. The family’s ownership in publicly traded Hero and other private assets gives Munjal a net worth of $3.8 billion.

“The future is going to be electric, collaborative and modular," Munjal said during the tenth anniversary broadcast. One factor in Hero’s favor is its financial muscle. Armed with more than $1 billion of cash on Hero’s books at the end of March, Munjal can spend heavily to get into the EV market. The company’s overall numbers this fiscal year to March were weakened, however, by the pandemic’s impact, as net profit fell 20 percent to 29 billion rupees on a 6 percent revenue growth to 315 billion rupees. The family’s ownership in publicly traded Hero and other private assets gives Munjal a net worth of $3.8 billion.

Being late to the EV party is a challenge, says Aditya Makharia, an auto analyst at HDFC Securities in Mumbai, as Hero will only be one of many when it finally enters the EV market. With Hero Electric already big in the market, and Ola Electric snapping up orders, Hero MotoCorp will need to carve out its own identity and market share, he says.

Munjal is no stranger to challenges. He is the son of the Hero group’s late founder, Brijmohan Lall Munjal, who died in 2015. After the family split the business in 2010, and parted ways with Honda in its joint venture, Hero had the right to use Honda technology through 2015 after that it had to develop its own engines and related technologies. The breakup, however, allowed Hero to ramp up its exports to global markets, which had been restricted by Honda to prevent the JV from competing with Honda’s own sales abroad. Munjal admits that Hero has yet to “make its mark" in exports—a minuscule 3 percent of the total 5.8 million units sold in the last fiscal year were exported—but he is aiming to make exports 15 percent of sales by 2025.

![]()

The pandemic struck India hard. Munjal was proactive in fighting Covid-19’s outbreak, shutting Hero’s six factories in India and one each in Bangladesh and Colombia days before the government imposed one of the world’s strictest lockdowns at four-hour’s notice in March last year. “You could see what was coming," he says. Hero employees switched to working from home, and the company started making sanitizers and masks as well as distributing meals in nearby communities. Munjal initiated daily Zoom calls with the leadership team so they could make real-time assessments and, as he describes it, put “lives ahead of livelihood."

Among the steps taken, the company created a Covid-19 zone-mapping dashboard that allowed it to adjust production levels depending on infection patterns around its factories. It also developed a system for anticipating supply bottlenecks by pinpointing which vendors were impacted and which needed support to bring employees safely back to work. Hero also started selling its two-wheelers online.

![]() Hero’s factory in Neemrana, Rajasthan

Hero’s factory in Neemrana, Rajasthan

When the Indian government began to gradually ease the nationwide lockdown from May 4, Hero was “ready to sprint," says Munjal. Within six months, it was producing 30,000 vehicles a day, up from 5,000 during the lockdown. In January this year, it crossed the 100-million-unit landmark in two-wheeler production, half of which came in the last seven years. “They handled Covid well," says analyst Makharia. With factories spread across India, Hero was able to quickly adjust production, “sometimes on an overnight basis," he adds.

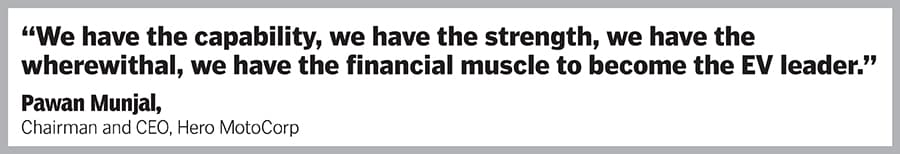

In gas-powered vehicles, Hero remains India’s leader in motorcycles, but has seen its market share erode in scooters, which declined to 10 percent in the last fiscal year from 18 percent a decade ago. It also has a tiny 5 percent of the high-end motorcycle market. To gain share there, Hero tied up late last year with Harley-Davidson after it exited India following its inability to gain a footing on its own in the market. Under the deal, Hero became the exclusive distributor of Harley-Davidson motorcycles, parts and accessories in India. It will also develop and sell a range of high-end motorcycles in India under the iconic American brand. Says analyst Makharia of Hero’s push into the premium end: “Whether they succeed or not is secondary, but at least their products are up there."

Looking ahead to the battle to take pole position in the two-wheeled EV market in India, Munjal says: “There is no fun if there is no competition, the more the merrier."

Pawan Munjal, chairman and CEO of Hero MotoCorp

Pawan Munjal, chairman and CEO of Hero MotoCorp The iconic Hero Honda CD 100, one of the first four-stroke motorcycles sold widely in India

The iconic Hero Honda CD 100, one of the first four-stroke motorcycles sold widely in India

Hero Xtreme 160R, which has a fuel-injected engine

Hero Xtreme 160R, which has a fuel-injected engine

The Global Centre of Innovation and Technology in Jaipur spreads over 250 acres and houses 1,000 engineers, research facilities, an auditorium and testing grounds for regular and electric models

The Global Centre of Innovation and Technology in Jaipur spreads over 250 acres and houses 1,000 engineers, research facilities, an auditorium and testing grounds for regular and electric models “The future is going to be electric, collaborative and modular," Munjal said during the tenth anniversary broadcast. One factor in Hero’s favor is its financial muscle. Armed with more than $1 billion of cash on Hero’s books at the end of March, Munjal can spend heavily to get into the EV market. The company’s overall numbers this fiscal year to March were weakened, however, by the pandemic’s impact, as net profit fell 20 percent to 29 billion rupees on a 6 percent revenue growth to 315 billion rupees. The family’s ownership in publicly traded Hero and other private assets gives Munjal a net worth of $3.8 billion.

“The future is going to be electric, collaborative and modular," Munjal said during the tenth anniversary broadcast. One factor in Hero’s favor is its financial muscle. Armed with more than $1 billion of cash on Hero’s books at the end of March, Munjal can spend heavily to get into the EV market. The company’s overall numbers this fiscal year to March were weakened, however, by the pandemic’s impact, as net profit fell 20 percent to 29 billion rupees on a 6 percent revenue growth to 315 billion rupees. The family’s ownership in publicly traded Hero and other private assets gives Munjal a net worth of $3.8 billion.

Hero’s factory in Neemrana, Rajasthan

Hero’s factory in Neemrana, Rajasthan