Hero Electric is set for a high voltage fight

India's biggest maker of electric two-wheelers gears up as its rivals, including Hero MotoCorp, firm up an aggressive plan to turbo charge the EV market

After all these years of hard work, there is no question of letting the throne and market share slip: Naveen Munjal, managing director, Hero Electric

After all these years of hard work, there is no question of letting the throne and market share slip: Naveen Munjal, managing director, Hero Electric

Image: Amit Verma

Chandni Chowk, 2001

Around noon, it started to get chaotic. Thousands of buyers paced up and down the serpentine bylanes of one of the busiest wholesale and retail markets of India. The shrill pitch of countless hawkers, the blaring of two-wheeler horns, jostling for every inch of space with rickshaw pullers, and the oppressive July heat created a perfect photo opportunity for Naveen Munjal. The budding street photographer wanted to capture the bustling energy of the street in one frame. The 29-year-old zoomed out with his camera lens, and aimed for a long shot.

The same year, in 2001, Munjal was trying his luck with another long shot. The deputy chief executive of Hero Cycles reckoned the time was right for electric bicycles. Two decades ago, the idea sounded outrageous, and the bold attempt was labelled as false bravado. For the young Munjal, the gambit made ample business sense. Electric cycles, he was convinced, could woo cycle owners who were reluctant to graduate to a scooter or motorcycle because of a steep price difference. “The gap was around ₹1,400 for a bicycle, and ₹44,000 for a bike or a scooter," recalls Munjal, who came up with a novel plan.

A heavy lead acid battery was mounted on the carrier of a black roadster bicycle, a motor and a controller were attached and, eureka, an electric bicycle was born. The product made enough noise in the market. Munjal expected an electrifying response but, in his own words, “it was a complete failure". The young entrepreneur was baffled. The price point, between ₹10,000 and ₹15,000, was affordable, the product provided better mobility, and it led to huge savings. But the consumer was not ready for it.

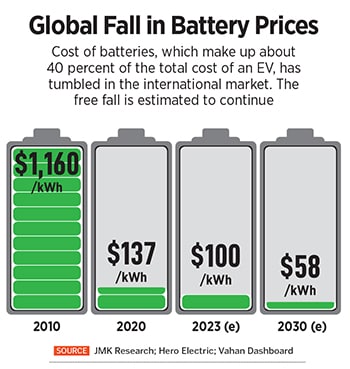

Three years later, in 2004, Munjal tried again. This time with an electric moped. The result was the same: It bombed. The reason this time, though, was different. “We were using lithium ion batteries, which were too expensive at $1,800," he recalls. The failure taught Munjal one clear lesson: That disruption in two-wheelers was inevitable and that they would eventually shift to electric. He adjusted his business lens, zoomed in with a sharper blueprint and started Hero Electric in 2007.

Five years later, the electric landscape in India was all charged up. Munjal’s company clocked its best ever sales numbers: 18,087 in FY12. From just 10 players in the two-wheeler EV (electric vehicles) segment in FY10, Hero Electric was in the midst of a high-pitched battle against two dozen players, most of them selling all kinds of imported EVs.

Then came the crash in 2011-12. The loud noise around electric got muted. In three years, two-thirds of the players vanished. Hero Electric’s performance too got dented as units sold tumbled to a low of 7,022 in FY15. As the electric euphoria started discharging, the EV segment fell silent.

Cut to July, 2021. The noise is back, and this time in the form of a loud ‘revolution’. Ola Electric, the electric venture started by the cab aggregator, claimed that it had received 1 lakh advance bookings for its electric scooter in just 24 hours. Bhavish Aggarwal, chairman and group CEO of Ola, sounded thrilled. “I thank all the consumers who have booked the Ola scooter and have joined the EV revolution," he tweeted. The company, which has raised $100 million in debt from Bank of Baroda, says it is building the world’s largest electric two-wheeler factory in Tamil Nadu. While the first phase will have an annual capacity of two million units, the target reportedly is to bump it to 10 million by end of next year. Aggarwal again took to Twitter to inform that Ola Electric has got reservations from over 1,000 cities and towns, and that it would launch the product on August 15. “Right from day 1 of deliveries, we’ll deliver & service all across India," he tweeted.

Cut to July, 2021. The noise is back, and this time in the form of a loud ‘revolution’. Ola Electric, the electric venture started by the cab aggregator, claimed that it had received 1 lakh advance bookings for its electric scooter in just 24 hours. Bhavish Aggarwal, chairman and group CEO of Ola, sounded thrilled. “I thank all the consumers who have booked the Ola scooter and have joined the EV revolution," he tweeted. The company, which has raised $100 million in debt from Bank of Baroda, says it is building the world’s largest electric two-wheeler factory in Tamil Nadu. While the first phase will have an annual capacity of two million units, the target reportedly is to bump it to 10 million by end of next year. Aggarwal again took to Twitter to inform that Ola Electric has got reservations from over 1,000 cities and towns, and that it would launch the product on August 15. “Right from day 1 of deliveries, we’ll deliver & service all across India," he tweeted.

With hyper aggressive marketing, high-decibel advertising, and a PR overdrive, Aggarwal successfully created a loud din. He was not alone in hopping onto the electric bandwagon in July. Others too, albeit in different avatars, got charged up. Take, for instance, India’s biggest pizza brand Domino’s, which joined hands with RattanIndia’s Revolt Motors to switch to an electric fleet. Swiggy, the online food delivery aggregator, has also started trials to deploy EVs in its fleet. It has inked a deal with Reliance BP Mobility Limited (RBML) to build an EV ecosystem and battery-swapping stations for its delivery partners across the country. The trials in Bengaluru, New Delhi and Hyderabad, the company underlined in its media release, are aimed towards its commitment to cover deliveries spanning 8 lakh km every day through EVs by 2025. The electric buzz is getting louder each day.

Meanwhile, a month later at his sprawling farmhouse in Delhi, Munjal is not letting the noise distract his focus. Fiddling with his DSLR camera, the managing director of Hero Electric is adjusting the lens for a close shot. “Competition is always good. It expands the market, amplifies customer awareness and offers more choice to buyers. More noise is getting created," he smiles.

A month earlier, in July, Munjal made a bit of a clatter of his own. Hero Electric raised the first part of its Series B funding of ₹220 crore, which was led by Gulf Islamic Investments, and saw participation from existing investor OAKS. The funding—which comes two-and-a-half years after Hero Electric raised its maiden round of ₹160 crore in December 2018 from Alpha Capital—will be used to expand its production capacity and beef up the EV play. “The market is exploding. In fact, we are not able to fulfil the demand," he underlines.

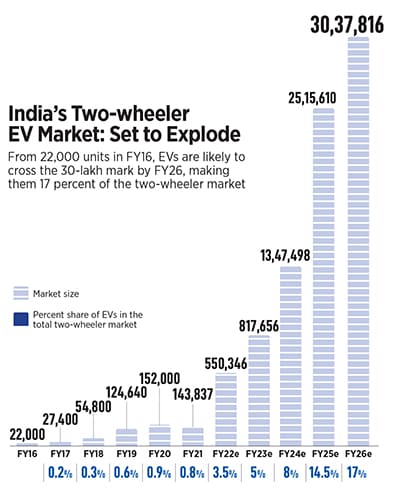

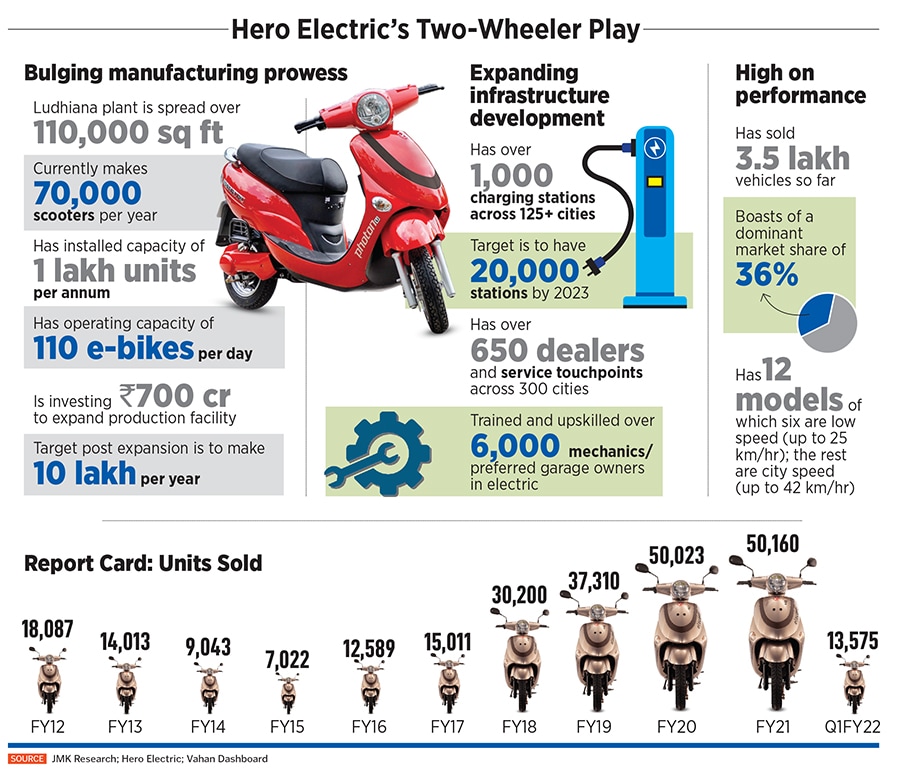

The man behind India’s biggest electric two-wheeler company, with a 36 percent market share, explains why the current euphoria around EVs is not a false alarm. The market, which was under 1.5 lakh units in FY21—just 0.8 percent of the overall two-wheeler market—is all set to explode. By FY26, the two-wheeler EV market is estimated to hit over 30 lakh, according to JMK Research. What this means is that in five years, the two-wheeler EV will account for a staggering 17 percent of the total two-wheeler market.

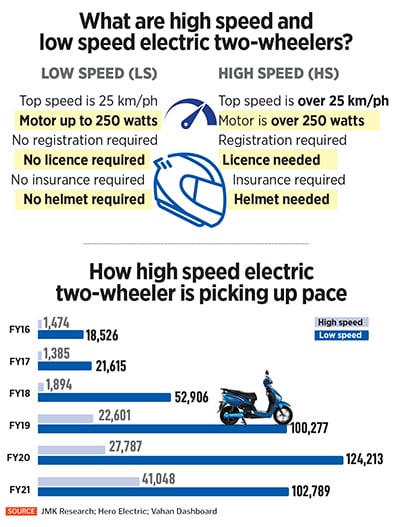

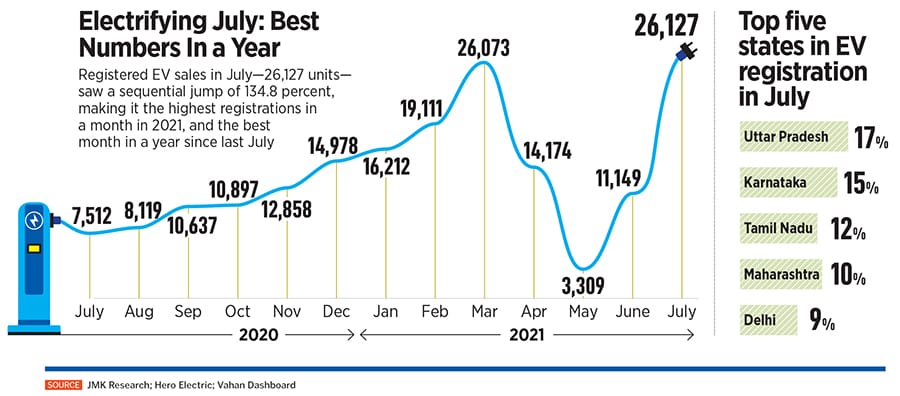

The reasons are not hard to fathom: Rising fuel prices, the increasingly bulging subsidy by the state and central governments, and the consistently falling cost of batteries have brought the once-prohibitive prices of an EV tantalising close to—in many cases they are at par with—petrol scooters. Hero Electric, which had a muted FY21 on the back of the pandemic, led from the front in bouncing back in the new fiscal year. From just 640 units of high speed EVs sold in April this year, the numbers pole-vaulted to 4,219 in July. Overall, registered EV sales in July—26,127 units—saw a sequential jump of 134.8 percent, making it the highest registrations in a month this year, and the best month in a year since last July.

Munjal is understandably delighted. The third-generation entrepreneur is now getting ready to amp up his game. The company plans to double sales in FY22, and has set an ambitious long-term target of clocking one million units (10 lakh) every year. Realistic? “Absolutely," he beams.

Munjal is understandably delighted. The third-generation entrepreneur is now getting ready to amp up his game. The company plans to double sales in FY22, and has set an ambitious long-term target of clocking one million units (10 lakh) every year. Realistic? “Absolutely," he beams.

The reason for his confidence? After spending two decades in the business of EVs, Munjal now knows the difference between ‘need’ and ‘want’. “This is something that took me a while to figure out," he confesses, explaining the difference. When people used to throng motor shows during the pre-Covid days, bookings and buying of EVs were more out of impulse. Now consumers, he stresses, need EVs.

The need, and the strategy emerging out of it, was quite evident even during the pandemic. Last April, Hero Electric rolled out a promotional offer by asking consumers to pay a non-refundable amount of ₹2,999 and book an EV which would get delivered post lockdown. The response was lukewarm. On digging deep and talking to loads of consumers over video calls, Munjal’s team found the reason. The prospective buyers were keen to buy, but the final nudge was missing. “They have heard of electric but never tried electric," says Munjal. What emerged was a three-day return policy. The vehicle was delivered, the consumers could experience it for three days and if not satisfied with it, they could return it. The gambit worked. Sales increased.

Another consumer insight also helped. When an EV buyer, Munjal stresses, talks about speed, it is not ‘speed’. In fact, it is torque. How quickly can a rider, he lets on, get off the blocks at the traffic signal when the light turns green has more to do with the torque and not with speed. The understanding of the nuance probably could be the reason why Munjal never talks about high-speed vehicles. He prefers to call it “city speed".

Auto analysts are not surprised with Hero Electric’s speed of growth. Munjal, they reckon, was the first one to hop onto EV bikes, and is one of the few still in the saddle after years of bumpy ride. “They stayed constantly invested in the EV space," points out Jaspreet Singh Bajwa, management consultant (automotive industrial consulting group) at Nomura Research Institute. Since the early days, Hero Electric was the only brand selling a reliable product, alluding to the phase when the EV market found itself glutted with players from the organised as well as cottage industries. Most of them sold Chinese assemblies that were highly unreliable and prone to breakdowns. “Hero’s strategic long-term game and planning for the EV segment have worked out great for them," he contends.

Auto analysts are not surprised with Hero Electric’s speed of growth. Munjal, they reckon, was the first one to hop onto EV bikes, and is one of the few still in the saddle after years of bumpy ride. “They stayed constantly invested in the EV space," points out Jaspreet Singh Bajwa, management consultant (automotive industrial consulting group) at Nomura Research Institute. Since the early days, Hero Electric was the only brand selling a reliable product, alluding to the phase when the EV market found itself glutted with players from the organised as well as cottage industries. Most of them sold Chinese assemblies that were highly unreliable and prone to breakdowns. “Hero’s strategic long-term game and planning for the EV segment have worked out great for them," he contends.

What also works for Munjal is the first-mover advantage. In Hero Electric’s case, though, the entrepreneur qualifies ‘first-mover’. “It’s never about being the first one to enter, but being the first one to do what nobody does," he explains. Back in 2012, when the industry was imploding and players were shutting shop, Munjal decided to service the EVs of the rivals through his network of workshops and dealers.

Though many players pedalled cheap, imported EVs—which because of their dismal quality started being perceived as toys—nobody built the infrastructure to service them. So when the brands disappeared, consumers panicked. Munjal decided to play saviour. “We didn’t want the industry to collapse," he says, pointing out another business reason behind the apparent philanthropic move. “We wanted some extra monies for the dealers."

The collateral benefits were massive: Goodwill, high brand equity and consumer stickiness. Hero Electric, points out Bajwa, has been able to achieve and deliver what many have not been able to do. It not only provided an affordable EV but also came up with a relatively good after-sales ecosystem to support the vehicles, he adds.

The going, though, might not be easy for the largest player. Competitors like Ola may be a threat, but a bigger one wil come from a member of the extended Hero family—Hero MotoCorp which is gearing up to roll out its own EV by next March. The ‘petrol’ hero and the biggest bike maker in India has been silently wiring its electric strategy over the last five years. In 2016, it invested in Ather Energy, and gradually hiked its stake to become the biggest stakeholder with a 38 percent stake.

A Hero MotoCorp spokesperson explains the “three-pronged EV approach" of the two-wheeler maker. First is through internal projects at its R&D hub. Second is through incubation centre Hero Hatch, and the third part is via a collaboration with external entities. In April, it announced a strategic tie-up with Taiwan’s Gogoro to deepen its electric play. Through this partnership, Hero MotoCorp will bring Gogoro’s battery swapping platform to India, collaborate on electric vehicle development and develop Hero-branded, Gogoro-powered mobility solutions. The partnership, Pawan Munjal, chairman and CEO of Hero MotoCorp underlined in a media release, would enhance the work and partnerships that Hero MotoCorp already has in its EV portfolio.

Internally as well, Hero MotoCorp has intensified its EV efforts. Through its incubation project—Hero Hatch—the company is focusing on developing alternative mobility solutions. One such interesting concept was showcased at the Hero World event in February 2020, where the Hero Hatch team unveiled an electric modular mobility solution: Quark 1 Concept, a three-wheeler that can be converted into a two-wheeler. At the same time, the auto major has been running projects exclusively dedicated to developing EVs at its R&D facilities—Centre of Innovation and Technology in Jaipur, and the Hero Tech Center near Munich, Germany. “The work on EVs within the company and investment in the external ecosystem bear testimony to its commitment to electric mobility," the spokesperson adds.

What gives Hero MotoCorp matching firepower in its electric play, reckon analysts, are three factors: Brand equity, high trust and financial might.

Tarun Mehta, co-founder and chief executive officer of Ather Energy, explains how Hero MotoCorp spotted an early opportunity to get into the game in 2016. “They were still framing their EV strategy but it was at an early stage," he says, adding that the company was keen to explore the electric ecosystem. They knew electric is going to be the future, their own EV products might take long and they didn’t want to stay out of the business.

Now that Hero MotoCorp is coming up with its own EV, Mehta is not worried. Reason: Both the companies are approaching the market from a different perspective. While Ather’s strength comes from high, well-integrated product experiences, Hero’s strength is in the mass markets with distribution that goes deep inside rural and Tier II and III towns, he explains. Every two-wheeler company, he contends, has to move towards 100 percent electric in the next five years. “Five years from now, if anybody’s still working actively on an ICE (internal combustion engine) portfolio, I think it’s downright dangerous," he says.

It’s not only Hero MotoCorp that plans to make a big-bang entry in the EV space. Bajaj Auto too is firming up its electric play. Last month, the biggest two-wheeler exporter from India decided to set up a 100 percent subsidiary to explore electric and hybrids. The idea, explains Rakesh Sharma, executive director at Bajaj Auto, is to ensure undivided focus to the development of the business, make it easier to attract talent and give the company agility to work in alliances.

While conceding that the auto industry is firmly set to move in the direction of electric, Sharma maintains that from a two-wheeler perspective, the timing of EVs becoming a significant component is still ambiguous as the rate of adoption is constrained by cost differences and to a lesser extent by convenient availability of charging. “Irrespective, we are looking at this change as an opportunity and not a threat," he says. Though competitors may invest heavily towards securing large volumes, Sharma explains, these days first-mover advantages are thin. “Ultimately, the fundamentals of performance, design, price and customer experience secure the competitive positions," he adds.

Back in Delhi, Hero Electric’s Munjal is not bothered with the action around. “It won’t be a walk in the park for the ICE players," he says.

“After all these years of hard work, there is no question of letting that market share and dominant position slip." He explains what gives Hero Electric an edge over the big petrol boys. First, the ecosystem of ICE players is not built to cater to electric needs. From dealership to strategy, it needs to start from scratch. The transition, he stresses, is not as simple as what a lot of companies make it out to be. “If you think you can suddenly do this, it’s not quite that simple," he says. While one can replicate technology in a year or so, one can’t replicate the DNA of an electric organisation.

ICE players also have too much at stake in petrol. Making an entry into electric, which all of them will eventually do, will end up cannibalising their market share. “Their coming in only lends credibility to the sector," Munjal smiles. It’s some sort of a validation of his electric vision. “There is a thin line between a fool and a visionary," he says. Munjal is not taking competition lightly and neither is he getting complacent. “It’s all about adjusting your lens and keeping your focus intact."

First Published: Aug 19, 2021, 11:02

Subscribe Now