The foreign company played its cards. The offer on the table for the Virani brothers was over ₹4,000 crore for selling out. “It was a lot of money,” says Chandubhai, but he was not surprised.

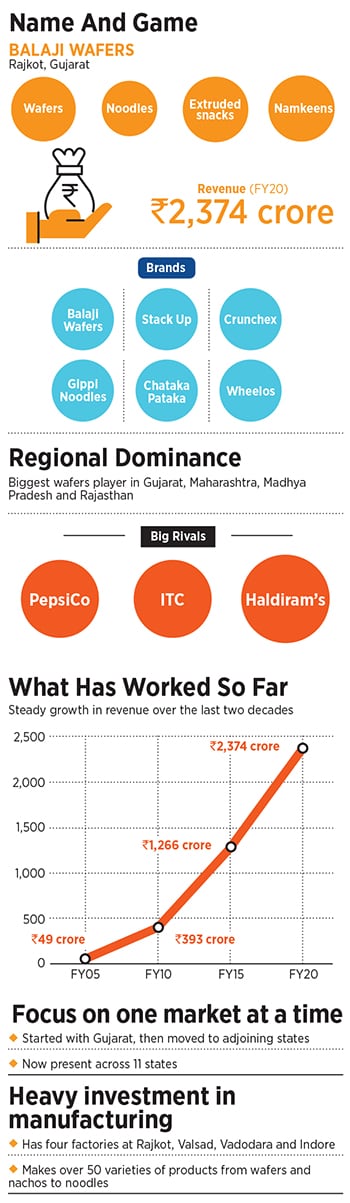

For the snacks industry, 2014 had started on a crispy note. In January, WestBridge Capital Partners picked up a 25 percent stake in DFM Foods reportedly for ₹64.5 crore. The Delhi-based company, which had blockbuster ring brand Crax, primarily catered to markets in north, west and central India. Two months later, private equity fund Lighthouse bought around 12 percent stake in the Rajasthan-based Bikaji Foods. The suitors were on the prowl.

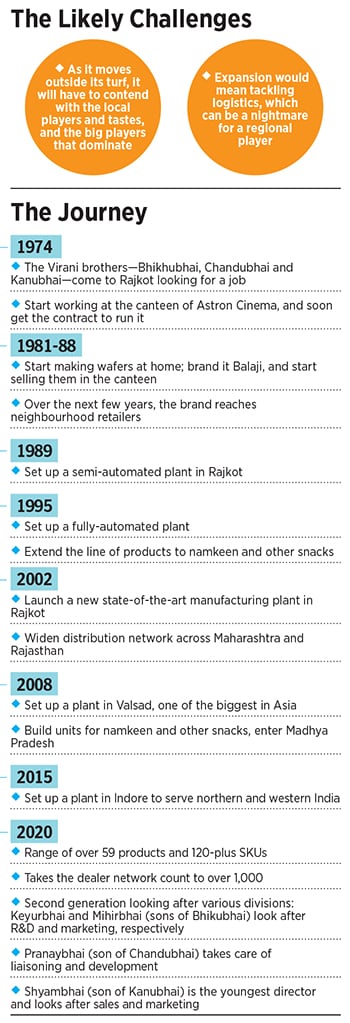

Back in Rajkot, Chandubhai was not impressed or overawed by the offer. “I have never feared anything or anybody,” says the founder and director of Balaji Wafers. “If they thought they could intimidate me with their size, they were wrong.” And he had the wind in his sales. Balaji had emerged as the biggest wafers brand in Gujarat and Rajasthan, and was among the top three in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh.![chandubhai balaji wafers chandubhai balaji wafers]() The perception in Rajkot, though, was different, at least among other regional brands there (including Rajasthan). One of them called up Chandubhai and impressed upon him the need to sell. “You know, companies are like daughters. After a particular age, you need to get them married, and send them to their new home.” Chandubhai stayed stoic. [qt]“This company is my daughter and my son. And I don’t sell my family,” [/qt]was his retort. The offer was nipped in the bud, and the Virani brothers, along with the second generation, got back to work.

The perception in Rajkot, though, was different, at least among other regional brands there (including Rajasthan). One of them called up Chandubhai and impressed upon him the need to sell. “You know, companies are like daughters. After a particular age, you need to get them married, and send them to their new home.” Chandubhai stayed stoic. [qt]“This company is my daughter and my son. And I don’t sell my family,” [/qt]was his retort. The offer was nipped in the bud, and the Virani brothers, along with the second generation, got back to work.

![snacks maker snacks maker]()

Six years later, a lot has changed. Balaji is the undisputed leader in four states and present across 11, and in the midst of a pan-India push. And revenue almost doubled to ₹2,374 crore in this period (till FY20). What persists is the stubbornness and passion of Chandubhai to keep building the company, and not to sell out or even dilute the family’s holding. “Why an IPO?” he asks. “I don’t need money. I never needed it.”

Back in 1974, when the Virani brothers were forced to migrate from their village in Jamnagar and come to Rajkot in search of a job, all that they wanted was a ‘name’ for themselves. “We never left our homeland in search of money,” says Chandubhai. Due to paucity of rain, his father sold the parched land and gave ₹20,000 to his sons to start a new life by moving out of the village. The trio started a small venture in agricultural products and farm equipment in Rajkot. It flopped after two years, and the brothers started working in Astron Cinema’s canteen. “My salary was ₹90 per month,” Chandubhai recalls. “And in 2014 I was offered ₹4,000 crore to sell my company,” he laughs.

At Astron Cinema, Chandubhai was dreaming big. Two developments helped him see the larger picture. One, getting the contract to manage the cinema canteen. The second was the popularity of the wafers sold at the theatre, with demand outstripping supply week after week. The Virani brothers decided to make potato chips at their tiny, one-room home. The Virani variety found takers, not just within the cinema hall but outside, too.

Balaji Wafers—the brand name inspired by a small glass idol of Lord Hanuman kept in the room of the Viranis—stepped out of the reel world.

The real world started with one big lesson: There is nothing called instant success. The Viranis spotted their first villains in a few retailers who either defaulted on their payments or cheated them by claiming that the packs sold were soiled. Undeterred, the brothers decided to widen their appeal, and reach. Loading bags of wafers on their cycles, and later on bikes, the brothers started moving from one hinterland outpost to the other. The quality and taste were garnering enough appreciation for Balaji to become the talk of the town over the next few years.

In spite of the initial success, Chandubhai was not willing to step into multiple territories. “One area at a time. One fight at a time,” says the 64-year-old. The progression has followed a fixed pattern. In terms of footprint, the first priority was to build ‘Fortress Balaji’ in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh over close to four decades, and only then stepping out in the adjoining areas.

[qt]Why an IPO I don"t need money. I never needed it. - Chandubhai Virani[/qt]

That’s not a strategy multinational food companies, with financial and marketing muscle, are known to follow. For many of them, India is one humungous market on a global stage. “Woh dimaag se kaam lete hain (They use their brain),” grins Chandubhai. “They have a fixed set of rules, a bunch of defined procedures, and fixation with business and profit. We are just the opposite. Hum dil aur dimaag donon istamaal karte hain (We use both: Our heart as well as brain),” he says. The heart part, Chandubhai underlines, comes from not having any sales or revenue targets. “We never chased targets. We never had one,” he says. The only thing the company cares about is how to bring happiness to its stakeholders: Consumers, retailers, distributors, and employees. “Can a PepsiCo CEO work on a potato farm? I can. I am still grounded. That is the biggest difference,” he says. The next generation at Balaji, he points out, has introduced the level of professionalism needed to keep Balaji modern and traditional. “Profit doesn’t give you business,” he says. “Business gives you profit.” The next generation at Balaji, he says proudly, understands this philosophy.

![balaji waffer balaji waffer]()

Shyambhai, the second generation entrepreneur, joined the family business in 2019 after studying economics from Clarke University in the US. “We are the only FMCG company in India that has zero targets,” smiles the 24-year-old, who started his stint with the sales and marketing department and now looks after future projects, including expansion. Ask the youngest director in the company how the machinery works without a target, and quick comes the one-word answer: Pull. “We just focus on quality, which is the biggest pull for consumers.”

[qt]Woh dimaag se kaam lete hain, hum dil aur dimaag donon istamaal karte hain. (They use their brain, we use both: Our heart as well as our brain). - Chandubhai Virani on MNCs[/qt]

Though Balaji might not be pushing its products, the company is definitely pushing its frontiers in terms of expansion to new geographies. “We are now going pan-India,” says Shyambhai, outlining the expansion blueprint. The first thing, he stresses, is to set up manufacturing facilities across the country. Balaji can’t supply to the new regions from the four plants it has across Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. “A new plant is coming up in Uttar Pradesh,” he informs. Next would be Delhi-NCR, South and East India. In terms of new products, wafer biscuits would be coming soon, apart from some ethnic snacks.

Balaji, reckon industry analysts, is only desi in name. In terms of the way the Rajkot-based company has run its operations, it’s nothing less or ever better than an MNC. “Material cost is at a staggering 78 percent, which clearly translates into delivering great value for money for consumers,” says KS Narayanan, a food and beverage expert (the average for the industry is 65 percent). Despite a 78 percent material cost, other costs are just 9 to 10 percent, showing it’s a well-run tight-knit operation, leading to about a 10 percent-plus profit margin on a consistent basis. Moreover, on an average, there are about 50 to 80 percent more wafers per pack. Selling and distribution costs—below 0.5 percent of sales—are a case study in efficient distribution management, he contends.

The other bright spot in the report card is the inventory turnover ratio, which is in the range of 25 (the industry norm is 15). This means an efficient management of finished goods (on an average about 15 days only), which has ramifications on stock freshness and inventory ageing. “These are critical for a category like foods and snacks,” says Narayanan. Trade receivables for Balaji, he points out, are almost next to nil averaging one to three days. This is staggering for a company of this size and magnitude. “The journey has been nothing short of spectacular.”

![harish bijoor harish bijoor]()

The road ahead, though, might throw a fair bit of new challenges for Balaji. The biggest is the move to enter new states in its quest to become a pan-India player. Marketing experts sound a word of caution. “There can’t be a one-country potato snack,” says Harish Bijoor, who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. What helped Balaji, he points out, in having an undisputed reign in four states was the proximity of the states and the time the company took to crack taste, and distribution: Three decades. New states will not only have established players, but also new sets of local variation in taste buds. “If the four states are bigger than many European countries in size, then what’s the need to explore new frontiers?” he asks.

![chandubhai balaji wafers2 chandubhai balaji wafers2]()

Chandubhai, for his part, contends that the move is not driven by greed. “We have never chased market share. All we want is a share of consumers’ love,” he says, adding that the company started with a vision to make a name for itself. “We never dreamt that we would come so far.” Balaji indeed has. Chandubhai, and the company he built with his brothers, reinforces one cardinal truth about desi Goliaths: It is easier for a small guy to see a big dream than a big guy to see one small dream.

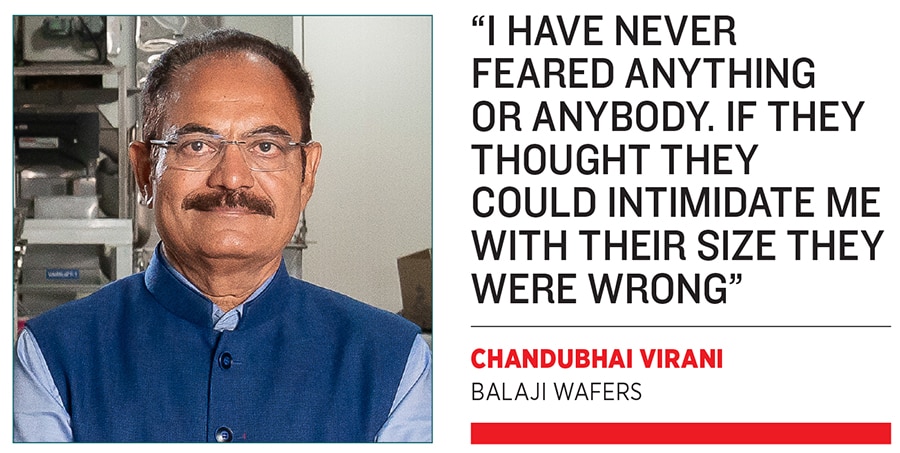

Keyurbhai (left), Chandubhai (centre) and Shyambhai Virani of Balaji Wafers at their Rajkot factory. The company is in the midst of a pan-India push[br]2014, Rajkot (Gujarat)

Keyurbhai (left), Chandubhai (centre) and Shyambhai Virani of Balaji Wafers at their Rajkot factory. The company is in the midst of a pan-India push[br]2014, Rajkot (Gujarat) The perception in Rajkot, though, was different, at least among other regional brands there (including Rajasthan). One of them called up Chandubhai and impressed upon him the need to sell. “You know, companies are like daughters. After a particular age, you need to get them married, and send them to their new home.” Chandubhai stayed stoic. [qt]“This company is my daughter and my son. And I don’t sell my family,” [/qt]was his retort. The offer was nipped in the bud, and the Virani brothers, along with the second generation, got back to work.

The perception in Rajkot, though, was different, at least among other regional brands there (including Rajasthan). One of them called up Chandubhai and impressed upon him the need to sell. “You know, companies are like daughters. After a particular age, you need to get them married, and send them to their new home.” Chandubhai stayed stoic. [qt]“This company is my daughter and my son. And I don’t sell my family,” [/qt]was his retort. The offer was nipped in the bud, and the Virani brothers, along with the second generation, got back to work.