The reason for the disbelief was a no-brainer. Atomberg was pitted against legacy players and industry Goliaths such as Bajaj, Crompton, Havells and Usha. “Who will buy your fans?" was the usual scepticism that greeted the founders. “You won’t be able to scale" was the regular dismissive prophecy made by umpteen marquee VCs and industry experts.

Das, meanwhile, was hoping against hope. “We had stretched ourselves to the maximum," recounts Das, adding that the odds were heavily stacked against the fledgling startup that was building fans which were designed to consume only 28 watts—this was 65 percent less than the energy used by the plain-vanilla peers—as against 75-80 watts by the much-famed rivals. “Forget the first choice, we were not even the last choice of the VCs," he says. Funders shied away from taking a punt on the greenhorns.

Ironically, the route taken to reach out to consumers gave more ammunition to the naysayers. “Are fans bought online? Can you sell them online?" were the two big questions staring at the founders who were trying to make a mark in an industry where the absence of offline distribution muscle resulted in the premature death of endless local challengers who dared to take on the might of the incumbents.

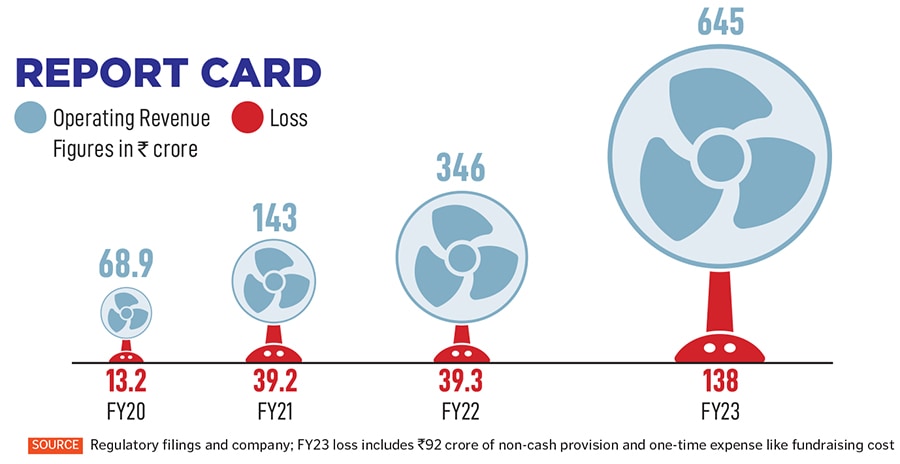

However, by early 2019, Atomberg had put on enough heft to muffle the critics. The numbers looked impressive. While the operating revenue for FY19 was ₹37 crore, Atomberg was producing 1,000 fans every day. “Still, we couldn’t find institutional backers," rues Das. Now in 2019, the blades of the fans were set to stop. There was no imminent funding in sight, salaries were getting delayed, and vendors started hounding for their pound of flesh. “We just had a lifeline of 30 days," he says.

![]()

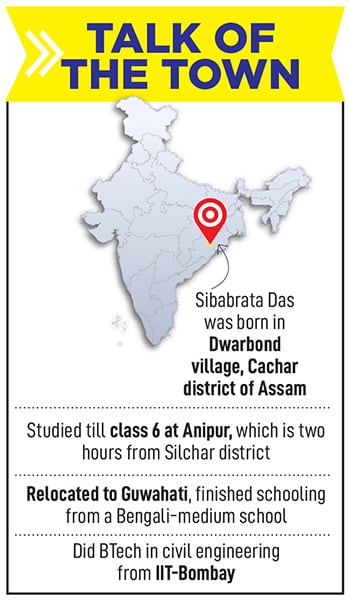

Back in a nondescript village in Assam, it was all about 730 days. At Anipur, a young Das, his family and scores of fellow villagers survived 730 days—two years—without electricity and water supply. Born in Dwarbond, a remote village snuggled in the Cachar district of Assam, Das got enrolled in a ramshackle local school where Bengali was the only medium of instruction. “My friends used to skip a few classes, step out of the school to take cattle for grazing, and then come back," recalls Das. Life progressed in slow motion, studies took a back seat, and there was little to complain about the laidback life. Like his father, most of the villagers worked in a nearby sugar mill, which got shut down when Das was in class IV.

The next two years were tough. The closure of the factory had a cascading effect. Erratic supply of electricity came to a sudden halt, and water supply too got disconnected. After two years of hardship, Das’s family relocated to Guwahati. Nothing changed, though. The patriarch continued with his relentless hustle, Das got enrolled into a government school where he continued his learning in Bengali and gradually got inducted into the elementary world of English, and the young lad discovered his talent for cricket. Nobody gave him a chance though. In one of the cricketing camps conducted in class VIII, Das enlisted himself. The team got selected on the second day of the three-day process, but a few players, including Das, were left in the lurch. “We were not given a chance, favouritism was at play, and the team was selected," he rues.

On the final day, however, a miracle happened. The coach tossed up the ball to Das and asked him to bowl an over. The young lad grabbed the opportunity, took three wickets in six balls, and impressed everybody. In fact, he stunned the coach by uprooting his stumps with sheer pace. As expected, Das made his way into the shortlist of 16, and then eventually found himself as the 11th player. Over the next few months, the lad lived up to his potential, and his name started popping up in local Assamese papers.

The happiness, though, was short-lived. When Das was in class IX, his father passed away. Das’s eldest brother had to drop out of college, and his mother started working. Suddenly, cricket went out of his life. The only mission in his life was studies, the only recreational activity that gave him happiness was walking through the steep hills a few kilometres away from his house, and the only indulgence was aalo paratha that his mother brought once in a fortnight. “Once a week we would get bakery biscuits, which we would ensure last for over 10 days," he recalls. Das was surviving on bare minimum resources, and the learning got inadvertently embedded in his muscle memory.

![]()

Months lapsed, Das cleared his class X papers, and decided to prepare for engineering. Though he exhibited enough enthusiasm, displayed keen intent and put in the required hours of intense preparation, nobody at his coaching centre—neither the teachers nor his batchmates—remotely expected a winner out of the village boy. The reason was his crippling handicap in comprehending English. “I used to take a long time to respond," recalls Das, who couldn’t clear the exams in his maiden attempt. Failure, though, was never an option for Das who made it to IIT in his second attempt.

Interestingly, during his IIT-Bombay days, Das had a string of failures as a fledgling founder. In his second year, he started a website development venture with his friend. The year after, he started trading in silk. “We used to export silk from Assam to Dubai," he recalls. In the fourth year, he started an online cosmetics marketplace, somewhat similar to Nykaa. All the ventures flopped. “Some didn’t have a product-market fit and some failed due to immaturity," he confesses. Giving up, though, was never an option.

![]()

Back in Mumbai, during the formative years of Atomberg, the resilience came in handy. For three years—2013 to 2015—the co-founders dabbled in various ventures. The initial gig of taking projects from institutions such as ISRO, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) fuelled the tech consulting business for a while. There was no scale, though, and the co-founders were still figuring out how to decipher the larger picture.

Then came a series of rapid-fire cameos: From a vehicle tracking system to a data acquisition device to three more ideas. Everything was tried, and everything bombed. “We were dubbed as failures," recalls Das. Friends and well-wishers advised the duo to take up jobs, many suggested that entrepreneurship was not for them, and the peer pressure—IIT-Bombay grads were in the news for raising funds for their respective ventures—was becoming unbearable.

![]()

Back during the IIT days, pressure was a constant companion. “I was at the bottom 5 percent," Das makes a blunt assessment of his pecking order. Interestingly, a few years down the line, Das again found himself at the bottom of the pyramid. This time the context was Atomberg’s offline presence. By April 2018, Atomberg had started producing 500 fans daily—it was 30 fans per day in April 2016—but its ability to scale at a furious pace was constrained by a lack of offline presence. “Nobody believed that the brand could make a dent in the brick-and-mortar world," says Das, who takes us back to his childhood days. As a young lad, Das used to walk for hours and climb treacherous hills. “I used to love the view from the top," he says. The initial hike, he adds, is the most difficult part of climbing. “But the exercise helped me conquer my fear," he adds.

As he grew up, the art of trouncing fear became a potent weapon. From engineering coaching classes to inside the college campus to the numerous bombed experiments in IIT and the tumultuous formative years at Atomberg, fear was always nipped in the bud. “The word doesn’t exist in my dictionary," says Das, who shares the secret sauce of slaying fear. “If you can navigate the initial turmoil, and if you have enough patience to ride through the storm, you will survive and grow."

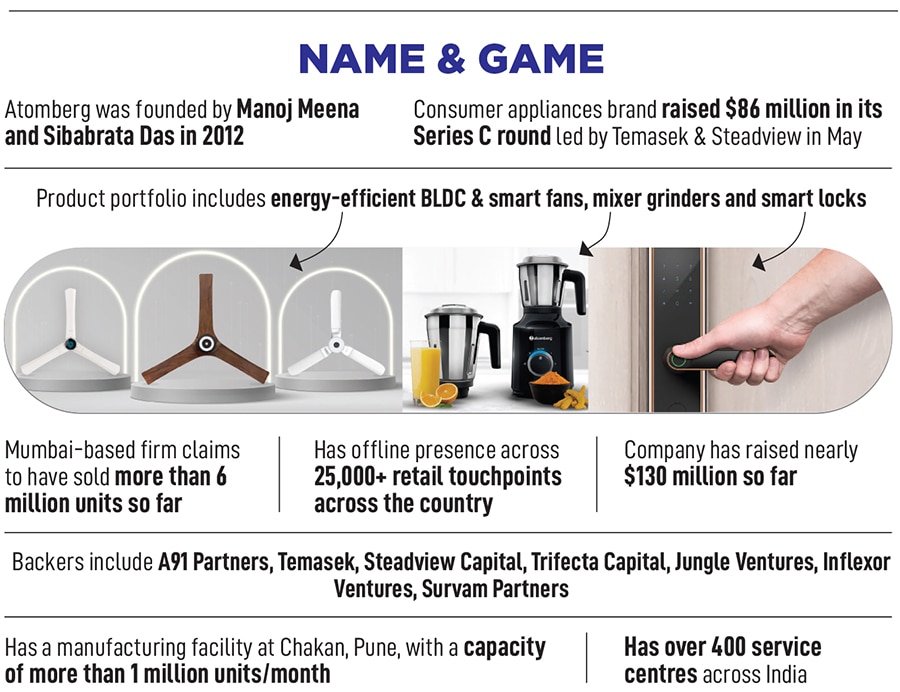

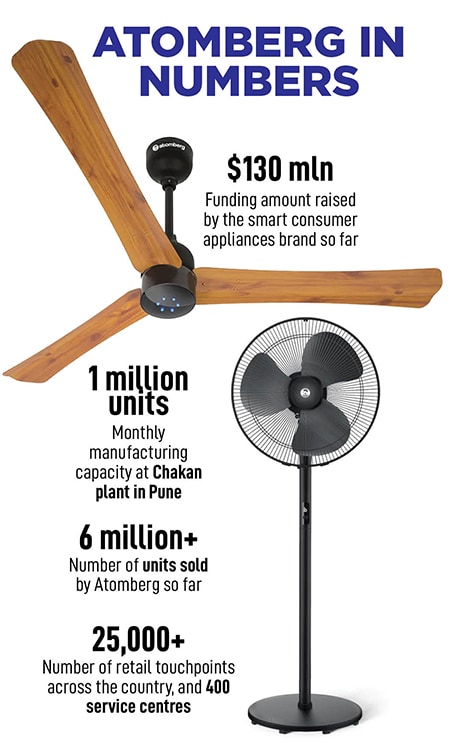

Das’s resilience, along with the gumption of his co-founder, who hails from Jaipur, gets mirrored in the growth trajectory of Atomberg. From an operating revenue of ₹68.9 crore in FY20, the numbers have pole-vaulted to ₹645 crore in FY23. The smart consumer appliances brand has raised $130 million in funding so far has a monthly manufacturing capacity of 1 million units at its Chakan plant in Pune claims to have sold over 6 million fans since inception and has built a vast retail footprint of over 25,000 touchpoints and 400 service centres across the country.

![]()

What is most impressive, though, about the founders is their venture. Vinay Singh explains. “Founders from small towns have typically better insights about the larger ‘India 2 or Bharat’ opportunity," reckons the co-founder and partner at Fireside Ventures, an early-stage VC fund backing consumer brands. Sibabrata, the VC contends, understood the importance of electricity bills for an average Indian consumer. Using this insight, they created a motor which helped in saving money. There are other founders from small towns who had a better pulse of the consumer pain points and needs, and ended up creating a product or service which is a much-needed pull rather than a push. Take, for instance, Animall. The co-founders are from IIT, but they were brought up in a family and culture where cattle played an integral part. “Now somebody from the city can’t even think, forget relate to, of starting such a business," he says. “This is what small town does."

Das, meanwhile, lists out his takeaways from his upbringing in a village and small town. “Humility is the most important trait," he says, adding that the quality gets reflected in the brand. “We have had several acquisition offers from big brands over the last few years, but we declined politely," he says. “We never said we will crush them all and be the biggest," he says. The second trait that got inadvertently ingrained in the brand DNA was ambition. “We are ambitious, but we are not impatient. We are hungry, but we are not greedy," he says, adding that the culture of ‘hire and fire’ is missing from the company. Commenting on his small-town upbringing, Das reckons that everybody gets an opportunity in life. What eventually differentiates success from failure is two things. First is an individual aware of the opportunity when it knocks. Second, if aware, did he/she grab it with both hands. “We did," he signs off.

The gloomy prediction of abject rejection and failure by experts, though, was a bit unfair and far-fetched. Incubated at the society for innovation and entrepreneurship (SINE) at IIT-Bombay in 2012, Atomberg started as a technology consulting venture, underwent a slew of pivots over the next few years, and in 2015, started building energy-efficient ceiling fans to supply to institutional buyers such as hospitals and colleges. A year later, in 2016, Atomberg made a transition from B2B to B2C business, and started selling fans.

The gloomy prediction of abject rejection and failure by experts, though, was a bit unfair and far-fetched. Incubated at the society for innovation and entrepreneurship (SINE) at IIT-Bombay in 2012, Atomberg started as a technology consulting venture, underwent a slew of pivots over the next few years, and in 2015, started building energy-efficient ceiling fans to supply to institutional buyers such as hospitals and colleges. A year later, in 2016, Atomberg made a transition from B2B to B2C business, and started selling fans. Back in a nondescript village in Assam, it was all about 730 days. At Anipur, a young Das, his family and scores of fellow villagers survived 730 days—two years—without electricity and water supply. Born in Dwarbond, a remote village snuggled in the Cachar district of Assam, Das got enrolled in a ramshackle local school where Bengali was the only medium of instruction. “My friends used to skip a few classes, step out of the school to take cattle for grazing, and then come back," recalls Das. Life progressed in slow motion, studies took a back seat, and there was little to complain about the laidback life. Like his father, most of the villagers worked in a nearby sugar mill, which got shut down when Das was in class IV.

Back in a nondescript village in Assam, it was all about 730 days. At Anipur, a young Das, his family and scores of fellow villagers survived 730 days—two years—without electricity and water supply. Born in Dwarbond, a remote village snuggled in the Cachar district of Assam, Das got enrolled in a ramshackle local school where Bengali was the only medium of instruction. “My friends used to skip a few classes, step out of the school to take cattle for grazing, and then come back," recalls Das. Life progressed in slow motion, studies took a back seat, and there was little to complain about the laidback life. Like his father, most of the villagers worked in a nearby sugar mill, which got shut down when Das was in class IV.