Most of the ‘contact sensitive’ sectors such as trade, hotels, transport, recreation and entertainment—which were hardest hit in the first wave—are more vulnerable to a double dip. Other sectors such as automobiles and construction which had shown a rapid recovery in demand after the lockdowns were lifted last year are starting to come under pressure once again due to rising caseloads and escalation of regional lockdowns.

Also, the threat to human life in the form of the contagious B.1.617 ‘double mutant’—which has now been traced to 44 countries—and possible future mutations of the coronavirus mean that the battle between vaccination and the virus spread will continue to be seen through 2021. The complications for India increase multifold if future mutations emerge as vaccine resistant. India has so far administered 17.59 crore vaccinations—13.77 crore people (9.9 percent of the population) have received the first dose and just 3.82 crore (2.7 percent of the population) have been administered both the doses.

It also means India will continue to see more rolling lockdowns across several states in the coming months. At least 12 Indian states are under a total lockdown, another four under a partial lockdown and three under night curfew to date.

Growth Forecasts Lowered

All these factors mean that business activity is, and will continue to be, impacted until mobility improves and contact-sensitive sectors are opened up fully or a sizeable portion of the population is vaccinated.

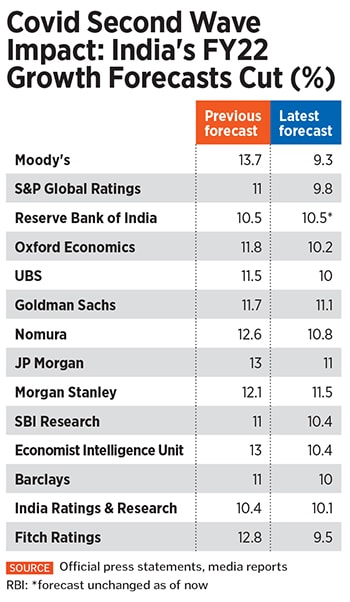

![]() In the past 4-5 weeks, several investment banks, equity research firms, ratings agencies have lowered their FY22 GDP forecast for India. The International Monetary Fund earlier in May said it will revisit its previous forecast (of 12.5 percent) for India due to the second wave, but declined to offer specific details. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is yet to revise its forecast, but governor Shaktikanta Das said stakeholders will need to “address the challenges posed by the current wave of the pandemic, while remaining on guard against future waves".

In the past 4-5 weeks, several investment banks, equity research firms, ratings agencies have lowered their FY22 GDP forecast for India. The International Monetary Fund earlier in May said it will revisit its previous forecast (of 12.5 percent) for India due to the second wave, but declined to offer specific details. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is yet to revise its forecast, but governor Shaktikanta Das said stakeholders will need to “address the challenges posed by the current wave of the pandemic, while remaining on guard against future waves".

Crisil’s chief economist Dharmakirti Joshi calls India’s second wave “a health care and economic challenge". The agency has kept a base GDP growth rate of 11 percent for FY22, but says that assuming the second wave would peak by May-end, India’s growth could dip to 9.8 percent. If the peak is delayed to June-end, growth would slip even lower to 8.2 percent.

Nomura’s India and Asia (ex-Japan) chief economist Sonal Varma paints a slightly positive picture. “We expect to see one quarter (April to June) of pain, after which a gradual relaxation of restrictions is likely as Covid caseloads fall," she tells Forbes India from her Singapore-based Nomura office.

The pace of growth in caseloads has been on the decline in the past few weeks. “With the restrictions, it appears that we may be peaking in May itself," she adds. India on May 6 reported a record 4.14 lakh new Covid-19 cases—and above four lakh cases for four consecutive days—before dropping off marginally since then.

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Research Centre on May 12 noted that the seven-day moving average of new Covid-19 cases in India is going down, alongside the United States, Brazil, Germany and France. Nepal, however, is showing an upward trend.

Nuanced Reopening

Varma now calls for a “nuanced" approach to reopening of the economy, once cases peak and start to come off. Sectors which are more likely to lead to higher caseloads will have to stay closed. These, Varma says, could include contact-intensive services such as full-capacity cinema halls, recreation centres and shopping malls, sports stadiums and public events, all of which have the potential to become super-spreaders. India can ill-afford to repeat an experience it faced, of calling off the Indian Premier League (IPL) 20-20 cricket tournament in May.

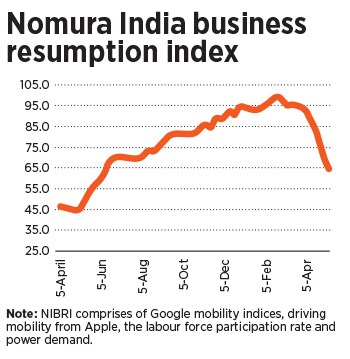

Nomura India’s business resumption index has been falling consistently since March this year (see chart).

![]()

The government was caught wrong-footed as it relaxed as caseloads fell after last September and testing slowed. By March 2021, Union Health Minister Harsh Vardhan claimed “end game" of the pandemic in India. No country, including those with well-developed health care systems such as Japan and Singapore, got their predictions right on the pandemic’s move.

The problems worsened for India due to a weak health care infrastructure which could not cope with the ferocity of the pandemic. The deficit of not having invested enough to build on social infrastructure is hitting the country hard. The higher level of base infrastructure and health care in other developed nations meant that they were able to deal with an incorrect prediction better.

Services Hurt Sectoral Troubles

Demand and supply of goods and services is starting to come under pressure, but it is nowhere as acute as seen in the first wave in 2020.

There is some similarity in how India and some Western economies reacted to the second wave. Due to targeted restrictions, partial lockdowns and peoples" adjustment to the new normal, demand for the services sector and consumer discretionary products such as cars has been impacted, but the rest of the economy continues to function relatively unscathed.

Passenger car sales have dropped by around 10 percent and two-wheeler sales by over 30 percent in April due to the rise in Covid-19 cases, lockdowns in several states and closure of dealerships, according to the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers.

Vehicle registrations show a 13 percent to 65 percent drop across categories in FY21. Maruti Suzuki has kept production of cars suspended at its Haryana plants till mid-week while there have been similar disruptions for Hero MotoCorp at all its factories in April and for Yamaha in May.

Banks have also turned cautious and despite ample liquidity, credit offtake, particularly towards the self-employed and small businesses, is low. RBI data pegged credit growth at just 5.6 percent for FY21.

Credit appetite from the urban salaried and corporates remains relatively unaffected in the second wave, as jobs and incomes remain relatively unhurt. But like last year, microfinance firms and unsecured lending to the self-employed face more risk as lockdown restrictions continue.

Thus lenders with a higher share of products, including loans against property, business/SME, urban microfinance, commercial vehicles (new) or unsecured products like personal loans, could see greater risk.

Anand Dama of Emkay Research estimates that the most affected states have a 48 percent share in systemic bank retail loans and 56 percent in overall credit. That said, India’s largest private lender, HDFC Bank, at an analysts call in April said cheque bounces have seen a “trend reversal" in April and were higher than those in March.

Rural growth, and incomes, have so far held up quite well so far. But supply chain disruptions are likely to increase as lockdowns extend in states. Mobility will hurt demand for consumer goods from giants Hindustan Unilever, Nestle and Britannia if the conditions worsen. Pressure is being seen in consumer discretionary demand and less on essentials.

Bullish Stocks: Narrative Not Changed

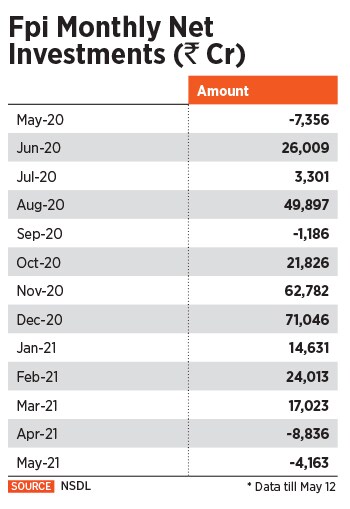

India’s stock markets have been remarkably stable in recent months, with the benchmark 30-share Sensitive index up by 1.71 percent year-to-date at 48,690.80 points on May 13. Foreign inflows into the equity markets have been positive for nine of the past 13 months (see table).

![]()

There’s a ray of hope also because of two successive quarters of positive FY21 earnings, which have been better-than-expected for several corporates. The commentary from business leaders has also been constant: That the disruption in the current quarter has not yet turned into a sharp dislocation.

Morningstar India’s Dhaval Kapadia, director, portfolio specialist, says investors seem to be looking beyond the next two quarters. Liquidity has also continued to boost sentiment. “In the first wave, there was massive uncertainty as no vaccines were available and the efficacy of these was not known. Also we have seen a strong revival in demand after the reopening," he says.

Gaurav Rastogi, founder of robo-investment advisory firm Kuvera, says the reason for the stock market bullishness is that the narrative has not changed from the first wave. “Spreadsheet numbers for corporates have moved by three columns, so demand pushed out by two to three quarters," says the Singapore-based banker-turned-entrepreneur. The markets would get spooked only if—due to multiple pandemic waves and shocks—business activity gets completely disrupted and results in the restructuring of business models.

The commodities super cycle is also starting to play out firmly. The global infrastructure expansion which the US and China talk about is likely to keep demand for aluminium, steel and oil up for some time. A lot will also depend on India’s commentary on commodities demand in the coming months.

Saurabh Mukherjea, founder-CEO of Marcellus Investment Managers, says: “There is optimism that once the second wave subsides, we will see an economic recovery, led by pent-up demand."

The stock markets are yet to factor in a third pandemic wave. Also, as the second wave deepens, the risk on spending and execution of the government’s mega infrastructure projects will increase, as would the execution of private sector capex cycles.

But Mukherjea explains the math which is keeping some of the index-based stocks firm: “If you take a leading franchise like HDFC Bank, Titan or an Asian Paints, even if we assume that over the next six months their earnings come under some pressure, for the next 19 years, their market share will be up by 10 percent from what it would have been without the pandemic."

So, the deeper the scar on the rest of the economy, the greater the positive impact on market leading franchises. The top 20 companies account for 90 percent of corporate India’s profit. Almost all of these companies have gained enormous market share despite the pandemic.

Fiscal Support Required

The real damage of the second wave, however, is still unknown as it has not abated. A complete opening up of the economy is risky, until herd immunity is reached, which also is a far way away.

Nomura’s Varma calls for fiscal measures quickly. “The government will need to provide support for state governments for the ramp-up of health care services and emergency units. Fiscal measures are also needed for the contact-intensive services and SMEs," she says.

The deepening of the second wave also pushes out timing on monetary policy normalisation. With inflation risks starting to play up again, policy normalisation can be expected only later this year.

Hence much of a ‘K-shaped economic recovery’ for India can only depend on the swifter implementation of vaccinations. The economy should be able to take care of itself after that.

Image: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Image: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images