Vellvette Lifestyle, founded in 2012, took its time making a mark, after raising seed funding of about Rs. 1.5 crore from venture capital firm India Quotient, which was raising its own first fund. The Mumbai company did not go far with its initial plan of selling curated make-up and personal care products from well-known brands on a subscription basis.

By 2015, Vellvette’s co-founders, wife and husband Vineeta Singh and Kaushik Mukherjee, changed tack and decided to make their own brand of cosmetics — SUGAR. Some investors did not believe it would work. The subscription-based ecommerce venture was something they were comfortable with, whereas, back then, a digital-led Indian consumer brand was “non-fundable,” Singh recalled in a recent interview with Forbes India.

“A couple of angel investors exited at the very next round of funding, but India Quotient continued to back us,” she says. Founding partners Madhukar Sinha and Anand Lunia’s belief in the entrepreneurs is seeing the kind of returns that VCs bet on. In February, Sugar Cosmetics announced a new round of funding, at $21 million, and in the process boosted its value to about $100 million.

Despite the pandemic, Singh, also the CEO, expects physical retail to be a big distribution channel for the digital-led company and she plans to go from being present in 10,000 stores today to 40,000 stores. India Quotient’s first investment in Vellvette is now valued at nearly 50 times over, based on a part exit in February.

“Sugar Cosmetics was a late bloomer among our portfolio companies from our first fund, which is doing extremely well,” Sinha, co-founder of India Quotient, said in a recent interview with Forbes India. “And that is our big winner from the first fund.” VC firms bank on one or two companies at best to return their entire fund many times over. “Sugar Cosmetics is that company in our fund I,” Sinha said. “We invested early in them and we just sold some equity in the company to return most of our first fund, and we are still sitting on a lot of unrealised gains.”

Lunia and Sinha started India Quotient in 2012, to test out their hypothesis that internet-led ventures could be the next big thing. They aimed to raise about Rs25 crore but exceeded that a bit to end with about Rs31 crore. Their timing made them perhaps the third full-time VC investors in early-stage startups in India after Blume Ventures and Kae Capital, which had both started in 2010.

The partners made 21 investments from that fund, and in the 2014-15 internet startup boom in India, their portfolio companies saw several markups, with follow-on larger rounds that drew investors such as Sequoia Capital and Tiger Global. Of course, most of the companies did not survive for the longer haul, but the markups showed that they were onto something. The experience also helped India Quotient raise its second fund—Rs. 109 crore this time, in 2015.

They would invest very early and typically take 10-12 percent equity stakes in the startups. While Sugar Cosmetics was the big winner among the investments from the first fund, others include Lendingkart, an online lender, and Highorbit Careers, which operated a jobs portal iimjobs.com, and which was acquired by Info Edge in 2019.

The ShareChat Bet

The second fund was an exercise in narrowing down the focus from internet in general to mobile internet and on to app-driven businesses. And one of the first companies India Quotient invested in, on the basis of this sharpened focus, was ShareChat, an Indian local-language social media company. India Quotient’s first investment in the company was Rs. 50 lakh.

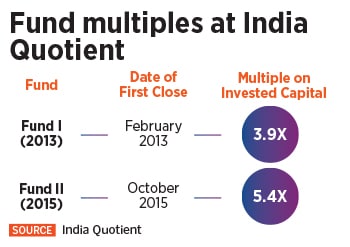

A small partial exit from ShareChat in 2018 helped the VC firm to be “very well placed” on returns from its second fund. By that time, already, India Quotient’s initial investment, made in October 2015, had grown over 500 times in value (See table).

![india quotient-2 india quotient-2]()

Mohalla Tech, ShareChat’s parent company, announced on April 8 that it had raised $502 million in a new round of funding, taking its value to $2.1 billion. It was previously valued at about $640 million, and it has now raised over $766 million in funding. ShareChat supports 15 Indic languages today and claims 160 million users. Moj, its short video platform launched only in 2020, has 120 million users, according to Mohalla Tech. Its retention and engagement metrics rival that of most global social media platforms like Instagram or Facebook or China’s TikTok, Sinha says.

While ShareChat is far from rivalling a platform like TikTok in terms of data or sophistication of its artificial intelligence algorithms, it is by far the most data rich venture among its peers and competitors in India, Sinha says. The fresh funding should help it deepen its technology, add more users, and start looking for ways to make more money. ShareChat’s revenues from its operations— at Rs. 9.4 crore for the year ended March 31, 2020, with losses of about Rs. 677 crore—are minuscule in light of its valuation.

Investors see huge potential. “As Internet penetration increases, ShareChat’s leading content creation platform is poised to expand dramatically by bridging into online purchases of goods and services,” Scott Shleifer, a partner at Tiger Global Management, said in Mohalla Tech’s funding press release. “Additionally, Moj is well-positioned to seize the opportunity presented by the growth of short video in India,” he said.

Among Mohalla’s investors are Twitter, Snap, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Tiger Global and Elevation Capital. “We have done very well over there,” is sort of Sinha’s stock understated observation, with India Quotient’s successes.

There have been premature successes too, as in the case of a venture that was building a social media app for doctors, where the founders decided to cash in their early success and sold within two years of starting. India Quotient got back five times its investment in that startup. Other fund II investments that are doing well now include Fab Alley, a direct-to-consumer women’s fashion company, and LoanTap, a fintech company that has notched up a loan book of over $80 million.

With the successes of the first two funds came greater confidence and ambition as well, and the third fund, in 2018, brought in Rs400 crore from the firm’s limited partners. With about 80 percent of the third fund now deployed, India Quotient has started talks with investors to raise its fourth fund, targeting about Rs600 crore ($80 million). The plan is to raise half of it from local investors by June and the rest from overseas investors by the end of the year to early next year.

Software for India

With the third fund, India Quotient is backing startups that make software for small Indian businesses. The VC firm is betting that there will be strong demand for software from startups that can make business software so user friendly that most small business owners will start using them.

That is the rationale behind India Quotient’s investments in Vyapar, and in a transportation software startup called Fleetx, which has gone on to raise funds from Beenext, and is doubling its sales every year. PagarBook is making a software suite for human resources and salary payments management. Sequoia Capital has already led two rounds of funding into this startup after India Quotient’s investment.

As mobile data penetrates deeper into India, India Quotient is betting that technology for agriculture will become a promising area. That, therefore, is another bet that Sinha and Lunia are making, with two or three investments in agritech startups.

“Broadly, our strategy is to identify trends that will become mainstream over the next 18 months to two years,” Sinha says. They then help seed companies that can ride those waves and each time if there are a couple of out-sized successes, the experience helps the firm go back and invest in more companies.

For example, news of Facebook’s listing in 2012 caught their attention and got them thinking about why India shouldn’t have its own social networking platform. “We were small investors with dreams in our eyes,” Sinha says. Two early investments, however, did not pan out. The first one shut down after raising about Rs50 lakh. The second was Roposo, a regional content app company that raised a seed round from India Quotient and Flipkart co-founder Binny Bansal in 2014. Roposo had gone on to raise more money from investors including Tiger Global, but was acquired in 2018 by ad-tech company InMobi.

While these startups didn’t become big, these experiences brought IQ plenty of feedback and ideas about what might actually work. Therefore, when ShareChat came along, in 2015, they weren’t entirely unprepared.

ShareChat’s success has prompted India Quotient to look at verticals and niches that might work in the Indian context. For example, they have now invested in a hyperlocal news and classifieds company called Lokal. Or take KuKu FM, which is an audio network, and Frnd, another audio-based dating company for tier two and tier three cities.

When IQ invested in Lendingkart in 2014, it was early days for online lending in India. That experience, however, helped them invest in LoanTap, Upwards and Prop Build. These are all very strong teams and will flourish in time, Sinha says.

Sugar Cosmetics was one of the first companies in India to use Instagram as a means to build a brand. That experience helped India Quotient to invest in Fab Alley. The firm has also invested in an online jewellery startup and a non-alcoholic beer brand.

The Dreamers

Sinha says India Quotient’s strength is its determination to stay small, but dream big alongside the founders it invests in. The partners typically go in when a founder’s idea is not much more than that, and there is little hard data available that can support the probability of success. With the first fund, cheque sizes were as small as Rs 50-75 lakh. So that means a seed round cheque in 2013 was, say, $100,000.

Today, taking into account increase in costs, such as real estate, cheque sizes remain small, and $250,000 to $1 million is the range in which the partners like to operate. They do not even want to go to the Series-A level in writing the first cheque to a startup, Sinha says, although they do selectively try to defend their ownership in really promising ventures such as Sugar or ShareChat.

Even with ShareChat, IQ’s ownership is now down to about 4-5 percent — including a partial exit in 2018 — from the initial 10-12 percent. Overall, IQ has made over 100 investments so far, according to data with Crunchbase, with 11 exits. The original duo also added partners. Prerna Bhutani joined around the second fund, and last year stepped back to become an entrepreneur herself. Gagan Goyal joined in 2017 and is a general partner now. Sinha expects the firm to add a few more partners and investment staff.

“We are more the dreamer kind of people, we are more near to the founders. We have founders come and say, ‘This is a great idea and this can be built,’ we try to dream along with them without having any data and solid ground for it,” Sinha says. “And then, we go by the trust, the gut and the sense of the market rather than company-specific data.”

That willingness to dream alongside a founder in the very early days gives the entrepreneurs a lot of leeway, says ShareChat’s co-founder and CEO Ankush Sachdeva. “They were always very open and flexible to allow the experimentation room for us entrepreneurs. Building a social product takes multiple major iterations to hit product-market fit. IQ proved to be a great investor in allowing us freedom,” he writes to Forbes India in an email.

“They understand Bharat better than most other investors. We had a lot of valuable discussions on how we should approach this problem statement” [of building a local-language platform], Sachdeva adds. “It is important to have contrarian investors like IQ in the ecosystem to push the envelope on what"s possible.”

Another unique attribute of them is that IQ portfolio companies tend to be very supportive and warm towards each other—that is very helpful in the early days, especially for young founders, he says. Sugar’s Singh echoes this: India Quotient has also succeeded in creating a good network effect among its portfolio companies, with both formal and informal events that bring them together, which often become problem solving sessions for the entrepreneurs. The portfolio companies are very active on WhatsApp groups, for example, and share and celebrate milestones and experiences. “That helps because as a founder, sometimes the journey becomes lonely.”

After the seed round, India Quotient also helped Singh raise her next couple of rounds, and the partners even helped the entrepreneurs out with personal loans during a “crux situation”. Money apart, “They always push founders to think bigger”, by providing context, benchmarks and perspectives about what competitors or other companies are doing and what might be possible. “That’s helped us aim higher,” Singh says.

Sachdeva adds: “IQ is also a long-term investor with strong conviction—they have continued to back across all our rounds so far.”

IQ raised a $30 million ‘Opportunities fund’ in 2019, from investors who were a bit more conservative, which it uses to invest in later rounds of promising startups. In many cases, however, they are happy to let their ownership go down to mid-single digits as larger investors come in. Sometimes, the partners have even offered their pro-rata rights to their limited partners to directly invest in some startups, and “they have done even better than us,” on those investments, Sinha says.

![india quotient-1 india quotient-1]()

On returns, Sinha says the metric of ‘internal rate of return’ is an inferior one compared with the number of times a VC firm is able to multiply the investors’ money. “We are in the business of multiplying wealth,” he says. On that front, money from the first fund has probably multiplied five times, and fund three, which is yet to even be fully deployed, is marked up by 1.8-1.9 times based on subsequent rounds of investments that have brought in other investors.

The real value of a portfolio of investments becomes visible only after the portfolio is four or five years old, Sinha says. The initial two or three rounds of funding aren’t enough to peg a company’s real worth or the chances that it will succeed or fail. “So we are all trying to throw darts. The next guy is equally blind and everyone believes that they are throwing the right darts,” Sinha explains.

Some things have changed though. Ten years ago, entrepreneurs used to be in their mid-thirties, with some ideas, financially more secure, but not too ambitious. Discussions would be around businesses that could grow to a couple of hundred crore. And the salaries of the founders, team building, which rights to negotiate and so on.

“Binny Bansal and Sachin Bansal changed everything,” Sinha says, especially, when their ecommerce venture Flipkart hit a billion dollars in valuation. That pushed a lot of engineering graduates from India’s prestigious Institutes of Technology to think about starting up, and of course the worry that a batch mate could go and start something that could become a billion-dollar business and “I would be earning half a million dollars at a consultancy and nobody is writing about me”, he adds. “We started seeing young entrepreneurs with no fear, talking about tech, about billion-dollar businesses.”

One of these new-breed of entrepreneurs, for example, was paying himself only Rs. 15,000 in salary and was at work at all hours, making life really tense for his team, some of whom actually complained to Sinha about it.

“I think we are entering into the golden phase of the startup ecosystem in India. I think India today resembles more like what China was ten years ago,” Sinha says. In a coming few years, he believes, there will be many large companies built in India. “We are very excited about the next decade or so for India.”"‹

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India