A year after ban, many Chinese apps make a comeback with a new interface

Experts say letting them function and allowing Chinese investments to fuel the Indian startup scene have allowed local apps to take over large chunks of the social media space

Image: Hemanshi Kamani"‹ / Reuters[br]

In one comic clip, Akshat Jain, popularly @crazy_akki, gets into a petty argument with his wife. She threatens to leave him and go back to her parents. Jain secretly rejoices until she calls her mother who says that to teach her rogue son-in-law a lesson, she was going to come over and stay with the couple. “Don’t make such a mistake…," writes Jain in his post on Tiki, a short video sharing app. “Else it will cost you heavy…"

Jain and his reel life wife Anjali Jain (unrelated) were diehard TikTokers where they had gathered 3.2 million followers when the government announced a sweeping ban on the ByteDance-owned short video service in June 2020. Fifty-eight other Chinese-owned apps, including WeChat and Baidu, deemed harmful to the “sovereignty and integrity of India" were also banned. The move stemmed from tensions with China over a Himalayan border dispute that led to an armed clash in which 20 Indian troops were killed.

At the time, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) said it had received “many complaints from various sources" that the apps were “stealing and surreptitiously transmitting users’ data in an unauthorised manner" to servers located outside India. In September and November 2020, the government added more Chinese-owned apps to its blacklist, including clones of those already banned, bringing the total to 267.

Even so, many banned Chinese apps are making a comeback, albeit with a different interface. Tiki, for example, made a quiet entry into the Indian market three months ago and is slowly notching up users. It is owned by Singapore-based Bigo Technologies, which, in turn, is owned by Joyy, a Chinese company listed on the Nasdaq. Bigo is also behind the banned apps Bigo Live, a live streaming platform, and short video app Likee. “We reverse engineered Tiki’s app and saw that the code is the same as Likee. They haven’t changed the library inside the code. They just put a new skin and launched it," says Sumit Ghosh, co-founder and CEO of Chingari, a short video service that saw a huge uptick post the ban.

Jain, who has signed a contract with Tiki to exclusively post his content on the platform, is unaware of the Chinese connection. “Tiki is a Singapore-based company," he says when prodded. “I used to use Likee earlier. The interface is very different from Tiki… it’s possible that the team members might be the same because they get poached," he reasons.

Similarly, while TikTok has been permanently banned from India as per a January 2021 order, Resso, a social music streaming app, which is also owned by ByteDance, hasn’t been targeted. It can be easily downloaded on iOS and Android devices and has been rapidly building a following. Tencent’s WeChat has been banned, but capital flows from the Chinese investor into Indian startups are welcome. Chinese smartphone makers Oppo and Xiaomi lead the Indian market with an estimated 72 percent market share even Zili, Xiaomi’s TikTok-like short video app, functions freely.

If data theft were a real concern, what explains these inconsistencies?

“They’re [the government] going after apps that have at least 10 to 15 million downloads," explains Ghosh.

Importantly, this porous strategy of allowing some companies to function freely while clamping down on others actually works to India’s advantage. Says Matt Sheehan, fellow at MacroPolo, an in-house think tank at the Chicago-based Paulson Institute, “When it comes to walling off a tech ecosystem, a certain level of inconsistency can actually be useful for policymakers. If foreign companies don"t know if or when an app might be allowed back in, that gives the government a lot of leverage over those companies… allowing Chinese investments to keep fuelling the Indian startup scene—all while blocking those startups" Chinese competitors—could be a way to bootstrap India"s own tech scene."

Lalamove India, for example, was banned in November 2020 by the government. But eager to still maintain ties and hopeful of returning to the market, the logistics player donated oxygen concentrators to Covid care centres across India—where it was headquartered—at the height of the second wave of the coronavirus. Similarly, after months of trying to engage with the government, TikTok shut its India office in January 2021, laying off 2,000 employees. However, earlier this month, the company reportedly wrote to the MeitY stating that it had complied with the controversial new social media and intermediary guidelines, which require companies like Twitter, WhatsApp and Facebook to regulate content, appoint compliance officers and enable traceability of messages. "Since day one of the ban, ByteDance remained committed to the country and wanted to engage with the government," says a former TikTok employee who spoke on condition of anonymity. "But it’s been status quo ever since. Despite sending detailed responses to the government"s queries, they never received an answer. Still optimistic about a fair dialogue, they retained all of us for six to seven months after the ban was announced. They paid salaries, gave promotions and did our appraisals. There was still hope."

India’s app ban can also be compared to China’s great firewall (GFW), albeit with caveats, says Sheehan. The digital barrier, implemented in the late ’90s, effectively cut off the domestic internet market from American competition. Local players filled the void and the ecosystem prospered.

A key difference concerns access to the internet. While China blocked it, India remains free and open. But given the leading position Chinese apps had in India—comprising six of the 10 most downloaded apps in India for 2019, according to data from Sensor Tower says Sheehan, “The app ban might turn out to be successful in clearing the way for Indian apps to take over large chunks of the social media space. I don"t think this was the Indian government"s main intention, but sometimes intent doesn"t matter as much as effect."

And so it is. A number of homegrown short video startups burst on to the scene in the days following the ban to fill the gaping hole left by TikTok which had 167 million followers in India at the time. While some have flourished, others have fallen by the wayside. Moj, a short video platform launched by ShareChat hours after the ban, has grown to 120 million monthly active users who spend an average of 34 minutes a day on the app, says CEO Ankush Sachdeva. It also raised over $500 million in a massive investment round led by Tiger Global in April 2021, propelling its valuation to $2.1 billion. Most of the funds will be used to fuel Moj, says Sachdeva.

On the other hand, Mitron TV, which started out with a bang, has pivoted to video editing. “Mitron is dead," says an employee at a rival short video platform on condition of anonymity. But Shivank Agarwal, co-founder and CEO, says their focus is equally divided between Mitron TV, its short video application, and Montage Pro, a video editing app it launched two months ago. “Montage Pro already has 7 lakh installed downloads. Overall downloads of MitronTV stand at 50-plus million on the Google Play Store" he says.

“Number of downloads is not an indicative metric," adds the employee. “You can download an app and delete it minutes later that’s still counted as a download. You need to look at daily or monthly active users (MAUs) for an accurate picture."

Others apps started out well before the app ban, but got a fresh impetus because of it. Like Chingari which was launched in November 2018 and had 3.5 million MAUs before the ban. Today, says Ghosh, the app has 70 million MAUs, mostly from non-metros, and counts actor Salman Khan as a brand ambassador.

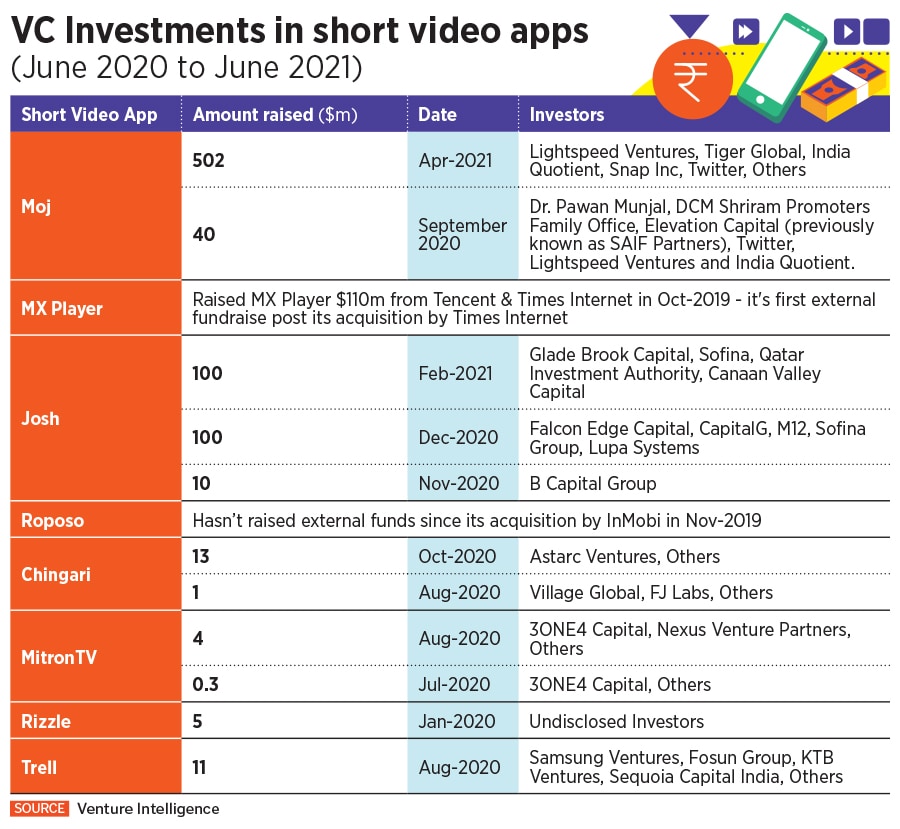

Besides Moj, the leading apps in the space include Times Internet-owned and Tencent-funded MX Takatak, Daily Hunt’s Josh app and InMobi-owned Roposo. Together they have raised around $750 million since June 2020, according to data provider Venture Intelligence. “Just four players have received so much funding. The short video space would not have grown at this scale and speed, if not for the ban," says Anil Kumar, founder and CEO of RedSeer Consulting. “India is at a tipping point. We produced more unicorns last year [13] than China [three]," he says.

Moreover, the app ban has spurred Indian innovation, especially in deep tech. TikTok was wildly successful because of its artificial intelligence (AI)-powered recommendation engine that served up exactly what users wanted to see. Local players have had to up their AI-play to fill that vacuum. ShareChat’s Sachdeva says their AI team has been scaled 3x over the last year and will grow further. “The pandemic has taught us the art of remote working, so we’ve been able to hire top notch talent from the US and UK to help us build out our AI capabilities."

Just as US President Joe Biden recently revoked the Trump-era bans on TikTok and other Chinese applications, what are the chances of the banned apps making a comeback in India? "ByteDance is a great company. If they really believed they could make a comeback, they would have retained us. It"s unlikely they will be able to re-enter," says the former TikTok employee quoted above.

Meanwhile, Jain, the comedian, who had partnered with Moj soon after the ban where he had notched up a cool 3.8 million followers before exclusively signing up with Tiki, says, “Indian apps are constantly improving. In the next three months, no one will miss using Chinese apps."

First Published: Jun 23, 2021, 13:29

Subscribe Now