3 Ps of profitability: How to bring Indian startup unicorns into the black

When promise, performance and profits converge, you get valuable unicorns

Every entrepreneurial journey starts with hope, and a promise. The founders put everything at stake. They know that the odds are heavily loaded against them—over 90 percent of startups fail—and yet take a leap of faith into uncertainty. The hope is to strike success in the long run. And the promise made to oneself is to build a valuable business.

To build and grow business, you need capital. Not all need the money, though. Many remain bootstrapped, but a chunk of the first-time founders do need the fuel, and reach out to VCs (venture capitalists). Now the investor, too, is living on hope. A VC puts the risk money in the fledgling ventures with a hope that the rookies would find the product-market fit, perform to the best of their abilities and grow the business. So the backer stays generous in doling out dollars, gives enough room to the hustlers to ‘fail fast, scale fast’, and course correct.

Tanked up, the venture starts rolling. At times, there are business pivots—while most are methodical, there are some where there is more ‘madness’ and less ‘method’. The journey continues, and on the way, the founders start making frequent mistakes (well, that’s how an entrepreneur learns and grows), ‘growth at all cost’ takes the front seat and CAC (customer acquisition cost) balloons. Loaded with venture dollars, ‘spraying and praying’ VCs don’t mind the cash burn. Riding pillion, all that matters to financers is an elusive pot of gold which they hope to get one day either through M&A, an exit or IPO. To be fair to them, this is why they invest: To make money.

Meanwhile, the founder starts performing, and the early years are all about growth. Revenue starts gushing, losses rack up, and the venture turns into a cash-guzzling machine. To be fair to a founder, there are segments where one must bleed to survive and grow. Take, for instance, ecommerce. When the name of the game is discount, there would be high CAC. And when there are deep-pocketed players, the intensity of fight and loss increases every day.

Meanwhile, the founder starts performing, and the early years are all about growth. Revenue starts gushing, losses rack up, and the venture turns into a cash-guzzling machine. To be fair to a founder, there are segments where one must bleed to survive and grow. Take, for instance, ecommerce. When the name of the game is discount, there would be high CAC. And when there are deep-pocketed players, the intensity of fight and loss increases every day.

Then there are sectors that need a change in consumer behaviour. The first-movers and leaders in such segments—Flipkart in ecommerce, MakeMyTrip in online travel, Paytm in online payments and Ola in cab bookings—will need much more capital to grow and stay put for largely two reasons. First, to create and expand the market and the ecosystem. Second, to induce consumers and build new habits. VCs are aware of the rules of the game. They keep pumping money in ventures that have a promising future, high user transactions and huge TAM (total addressable market). This leads to high valuation, at times insanely exaggerated, and startups enter the billion-dollar club. In May, India got its 100th unicorn when neo-banking startup Open raised $50 million. Industry analysts were quick to point out that one out of every 10 unicorns was being born in India.

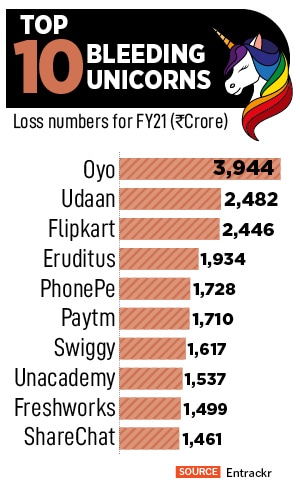

So the unicorn stable starts swelling. Along with valuation, what also gets alarmingly inflated is loss. Have a look at the FY21 numbers of these unicorns. Cred, a credit card payment platform which is valued at $6.4 billion, posted a loss of ₹524 crore. The operating revenue was just ₹88.6 crore. ShareChat, a social media unicorn with a valuation of $5 billion, reported a loss of ₹1,461 crore on an operating revenue of ₹80.3 crore. Online edtech unicorn Unacademy had a loss of ₹1,537 crore (revenue was less than one-third the loss) Curefit’s bottom line too is not eye-pleasing: ₹671.2 crore loss on a revenue of ₹161.4 crore, according to numbers shared by Entrackr.

So the unicorn stable starts swelling. Along with valuation, what also gets alarmingly inflated is loss. Have a look at the FY21 numbers of these unicorns. Cred, a credit card payment platform which is valued at $6.4 billion, posted a loss of ₹524 crore. The operating revenue was just ₹88.6 crore. ShareChat, a social media unicorn with a valuation of $5 billion, reported a loss of ₹1,461 crore on an operating revenue of ₹80.3 crore. Online edtech unicorn Unacademy had a loss of ₹1,537 crore (revenue was less than one-third the loss) Curefit’s bottom line too is not eye-pleasing: ₹671.2 crore loss on a revenue of ₹161.4 crore, according to numbers shared by Entrackr.

VCs talk about the flip side of growth without profit. “The product-market fit you are getting in high-burn businesses is not the right business," reckons Niren Shah, managing director and head of Norwest India. This probably explains, he underlines, why even large listed companies are facing the issue of profitability. “Product-market fit and unit economics are mutually exclusive," he says. Many get the first without getting unit economics. But the real problem starts when you try to fix the latter. “And then you realise that your product-market fit is gone," he adds. “It’s easier to make revenue without profit." Conceding that one can’t post profits overnight, Shah reckons that one should at least try to hit the road to profitability early in the innings. “There has to be an intent, a serious intent," he says.

Sustainable, indeed, is the key word. Shah tells us what went wrong with the ecosystem so far. “The founders hit the gym and only built the upper part of the body. They became muscular," he says, alluding to the growth and scale achieved by the startups. Now Shah tells us what needs to be done. “VCs must also tell them to build leg muscles as well. Unless you have solid legs, your muscular torso won’t add value," he underlines. When promise, performance and profit (3 Ps) come together, you get a valuable company.

The hope of future growth also gives rise to another hope: Future profit. While B2B businesses don’t need much time to post profit, B2C is a different game. Then there are the nuances of scale, segment and competition. Gupta gives the example of Lenskart. “There is no dogfight. It’s not a Swiggy-Zomato or Amazon-Flipkart kind of bleeding fight," he says. In spite of that, Lenskart took a decade to post profit. “Let’s be more patient. They will grow sustainably," he adds.

The hope of future growth also gives rise to another hope: Future profit. While B2B businesses don’t need much time to post profit, B2C is a different game. Then there are the nuances of scale, segment and competition. Gupta gives the example of Lenskart. “There is no dogfight. It’s not a Swiggy-Zomato or Amazon-Flipkart kind of bleeding fight," he says. In spite of that, Lenskart took a decade to post profit. “Let’s be more patient. They will grow sustainably," he adds.

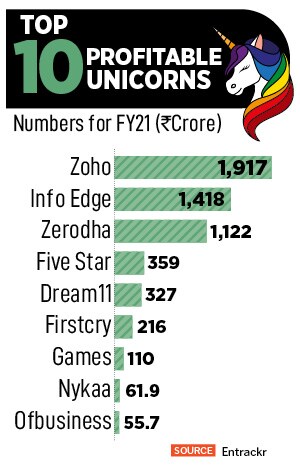

In this special issue on profitable unicorns, Forbes India decided to not take a deep dive into the storied tales of Zoho, Zerodha and their likes. The idea was simple: To talk about the other shades of unicorns that are not widely known or seen. Take, for instance, OfBusiness and Oxyzo. It’s rare to have two profitable unicorns co-founded by a husband-wife team, along with a few others.

Then there is Lenskart, which stayed in loss for over a decade and now has posted three consecutive years of profit. Another interesting story is Mamaearth. It’s not easy for consumer brands to post profits. This D2C beauty brand has had two back-to-back years of profit, plus a blistering pace of growth: From ₹22.19 lakh to over ₹900 crore in operating revenue in just six years! And not to forget the bootstrapped outsider—EaseMyTrip—which got the unicorn tag handed by the public market valuation.

First Published: Sep 12, 2022, 12:18

Subscribe Now