The Steady Rise of Pune's Kolte-Patil Developers

Pune developer Kolte-Patil fixed its house and made profits when most others are struggling. Now it has drawn up a plan to enter the top league

Sujay Kalele remembers the scepticism when he made his first presentation to the Kolte-Patil board in early 2011. Shortly after taking over as chief executive in January 2011, Kalele had been tasked with setting the agenda for the next three years. He’d worked out the numbers and made a fair assessment of where the company would be. He felt there was very little room to go wrong. Still, when the 31-year-old presented the numbers, the reaction was one of disbelief.

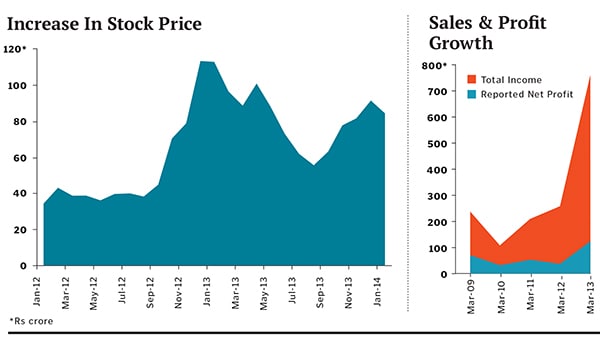

Kolte-Patil, the Pune-based firm which has been in business for two decades, had seen its revenue halve to Rs 107 crore in the year ended March 2009. Kalele projected that by March 2013 they’d reach Rs 800 crore in sales. A stunned silence followed. People in the room wondered whether he was being a tad too optimistic. Remember, the memories of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and the drying up of demand for new office space was still fresh in their mind.

But as Kalele explains, “I knew that these were the projects we had to launch. Permissions were there. It was now up to us to execute and construct. Revenue would follow.” Sure enough, the company ended March 2013 with Rs 764 crore in sales and an impressive post-tax margin of 17 percent.

“Their delivery track record is impressive. They’ve taken timely steps and reached far,” says Shobhit Aggarwal, managing director, capital markets, at real estate services firm Jones Lang LaSalle.

It is from here that the company has set up an ambitious plan to grow and be counted among the top league of real estate developers in India. Sure, it doesn’t have the swagger of some of its Mumbai counterparts or the dependability that some Bangalore-based names are known for. But as the last three years have shown, timely delivery and right pricing is more important to building a sustainable business than large land banks. It’s a story that is just beginning to be taken note of by the markets. In the last year, the company’s stock has trebled from Rs 30 to Rs 90. It is also the first real estate company to announce a 45 percent payout of profit as dividend.

Recently, Kolte-Patil, which also has a presence in Bangalore, entered the Mumbai market with two society redevelopment projects. Here too its aim was simple: Margin expansion. The aim for the next three years is to double revenue to Rs 1,500 crore and have a presence in more markets. Not bad for a company which, just a decade ago, was doing just Rs 10 crore worth of business.

The Early Years

In 1989, when Rajesh Patil entered the business started by his father, he could have hardly imagined the many twists and turns it would take over the years. At that time the company would operate from Jalgaon in Maharashtra with a very simple business model: Buy land and build one-storey row houses. Cash flow from construction would pay for the land and once the project was complete, they’d move on to the next development.

Patil, finding the scale too small for his liking (plus, he says, as a civil engineer, the type of work was not challenging), moved the business to Pune, which held larger potential. Here he managed to work jointly with land owners and would move from project to project. This was in the early 1990s, and he says his family insisted that he wouldn’t over-leverage for land purchases or get into bed with politicians. As the company grew, Patil also realised that systems and processes were what would get them ahead.

Patil’s big break came in 2003 when real estate markets in India were poised for an upswing. The company’s saleable area (in Pune and Bangalore) increased to a million sq ft and his firm also got into IT Parks. During this heady phase for the realty sector, the company grew rapidly—there was an IPO in 2007—only to see sales fall by half in 2008. After this, Patil says the second phase began, which was one of consolidation and getting systems and processes in place. “We must admit we took our eyes off the ball,” says Patil.

Getting back on track

Getting back on track

The period after 2008 was cathartic for developers across the country. Earlier, land banks were seen as an asset. Now they were more of a liability due to the interest payments they sucked out. “Fortunately, we had never treated land as an asset but more as a raw material,” says Kalele. “This lessens the confusion in our mind.”

Kolte-Patil decided to become an organisation that was focussed on working capital. Each project was evaluated from this parameter and interest costs were kept as low as possible. It was here that the company decided to enter the Mumbai market. Now, one might think that this is a particularly difficult market to get into but one look at the numbers reveals why it is much better from a cash management point of view.

Mumbai is a city that has thousands of buildings that are in urgent need of being torn down and rebuilt. Members of the housing society select a developer who tears down the apartment block and reconstructs it. Existing owners get new and larger homes, while the developer gets houses to sell—a win-win for both.

Here Kolte-Patil looked at what it would cost to set up two similarly profitable projects. Take, for instance, developments in Pune and redevelopments in Mumbai, where the company makes a similar profit.

In Pune, the company sells at an average of Rs 4,000 a sq ft. Land costs are Rs 1,000 a sq ft and construction costs amount to Rs 2,000 a sq ft. That means profits come from the last 25 percent of flats sold. Now, assuming it takes Kolte-Patil 18 months to sell 75 percent of flats, its working capital is stuck for at least 18 months.

Contrast that with Mumbai, where Kolte-Patil has got into redevelopment projects: It has to pay housing society members to vacate so it can start construction. As a result, the capital blocked is a lot less. At times all the company has to do is sell a couple of houses in the development to make up for the money that is blocked.

Same profit with a much lower investment made getting into Mumbai a no-brainer.

Equally important to Kolte-Patil is affecting change in the organisation that allows the company to ride this growth. “I found that everyone was working in silos,” says Kalele. “This is not something that would allow us to grow rapidly. At some point we’d fall flat on our face,” he says.

For instance, marketing knew what flats they could sell but this is not something that was always communicated to the planning team. Discounts were ad hoc.

Kalele tied up with IBM to help prepare the company for the next phase of growth. As a first step, IBM is working on internal systems that allow Kolte-Patil to become more customer-centric, align sales teams to pricing, and get marketing teams on the same page as campaigns. Then there is the issue of managing cost. “A common issue with builders is that workers have arrived but material hasn’t,” says Clifford Patrao, executive director of strategy and transformation at IBM India. “How does one plan for the life cycle of a project? How does one look at synergies across projects?” These are some of the questions Kolte-Patil is working on.

As Kolte-Patil has gone from being primarily a family-run operation to a professional-managed company, there has been the inevitable parting of ways with the old guard. “Earlier, when someone would leave, I would feel very bad. But in a professionally managed setup departures are a part of life,” Patil rationalises.

Going forward, Patil says the company plans to continue to focus on execution. He’s confident that even in a slowing economy he can sell 2.5 million sq ft a year. The company has a land bank with a saleable area of 40 million sq. ft, which it will bring on-stream once approvals are in place. It has also launched a luxury brand, 24K.

One looming uncertainty, according to Patil, is the 2014 general election. In the absence of a pro-growth government, he says he may have to hold back launches. Still, his long-term aim is to reach Rs 5,000 crore in sales. Given the heady growth in the last three years, it’s hard to see why this won’t happen.

First Published: Jan 28, 2014, 07:40

Subscribe Now