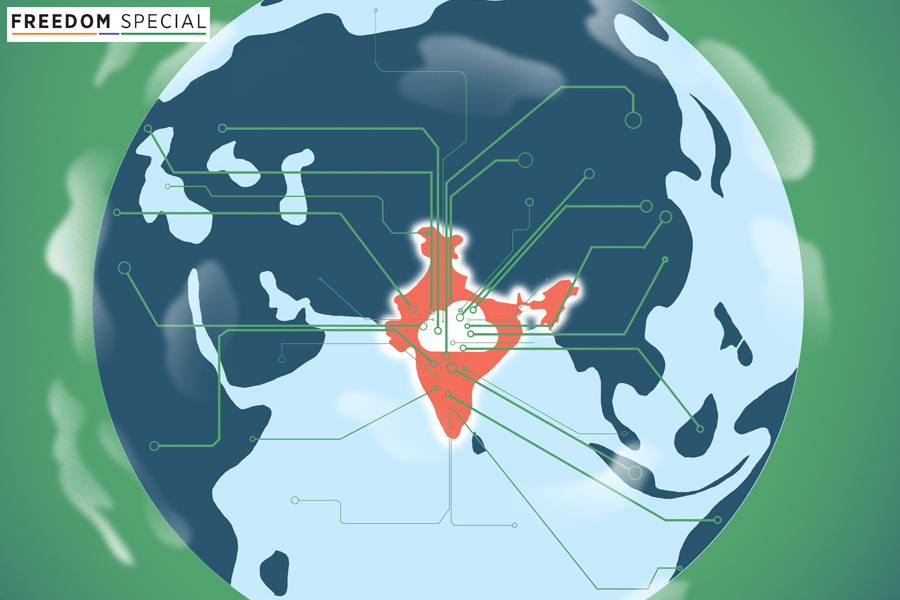

How India can birth software product giants

Several factors need to come together to create an ecosystem that enables and encourages the creation of global software products

India has shown the promise to create global-sized category winners in verticalised space in enterprise/SaaS, but we don’t have a clear path ahead either in consumer or platforms

India has shown the promise to create global-sized category winners in verticalised space in enterprise/SaaS, but we don’t have a clear path ahead either in consumer or platforms

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

The Indian IT and technology industries are on a roll. IT services is shining, courtesy its overwhelming more than 60 percent global outsourcing market share. The startup space is booming with venture capitalist (VC) and private equity (PE) investments starting to rival Indian public market inflows via FDI, FII the country already has 56 unicorns, with 20 of them being born in 2021 itself. The pandemic has dramatically accelerated mass digitisation and internet adoption. The IT Industry is showcasing all this optimism via burgeoning internet usage, increased investment flows, growing valuations and a deepening marketplace of digital products and services.

The Indian IT and technology industries are on a roll. IT services is shining, courtesy its overwhelming more than 60 percent global outsourcing market share. The startup space is booming with venture capitalist (VC) and private equity (PE) investments starting to rival Indian public market inflows via FDI, FII the country already has 56 unicorns, with 20 of them being born in 2021 itself. The pandemic has dramatically accelerated mass digitisation and internet adoption. The IT Industry is showcasing all this optimism via burgeoning internet usage, increased investment flows, growing valuations and a deepening marketplace of digital products and services.

One area that continues to be a bit of a vacuum is the global software products space. We don’t have any notable successes yet, and the country is largely beholden to the stranglehold of America’s FAANG companies. When will India produce its own versions of Google, Apple, Microsoft, is a question that gets asked around in Indian tech circles often.

India isn’t what comes to mind when thinking of the most innovative, successful global software products, but it won’t be a stretch to say that we have certainly started blipping on the radars. Ten years ago, if you were to ask the question, ‘where will the next generation of global software product companies come from?’, India would have drawn a complete blank. That’s not the case now. Let’s separate the software products space into its constituent buckets. Three segments emerge: 1) Enterprise/SaaS applications, 2) consumer products, and 3) core platforms/infrastructure.

In the enterprise/SaaS space, India is clearly on a promising glidepath and is fast emerging as a nursery of next-gen SaaS products that will make a mark on the world stage. Startups like Zoho, Freshworks, Dhruva, Postman, Browserstack, Innovaccer and Signeasy are emerging as category leaders in their respective segments. Something that has worked is the emergence of a replicable global playbook that came from the trendsetters (Zoho, Freshworks) Other startups have been quick to learn and adapt the playbook to their advantage.

In the consumer space, while some companies like Zomato, Oyo, Paytm and Ola have started expanding to foreign markets after establishing their dominance in India, it’s still very early days. And in the hyper competitive world of social and professional networking, messaging, video, meetings, communications, gaming etc, India hasn’t chalked up any global winners. In core platform areas like programming languages, operating systems, cloud computing, artificial intelligence/machine learning systems, robotics etc, again the Indian industry is found wanting.

Summarising the overall scorecard, it’ll be fair to say that India has shown the promise to create global-sized category winners in verticalised space in enterprise/SaaS, but we don’t have a clear path ahead either in consumer or platforms.

It’s worth taking a step back to understand why India finds itself in this position of being a relative non-starter on the global software products stage. There’s probably a multiplicity of cultural, economic, and psychological factors at work here.

Cultural aversion to risk, ambiguity and failure: Indian society traditionally values conformity and prepares us not to fail. But building products is all about managing risk and failure. You must take on multiple types of risk: Market risk, execution risk, product risk. For many Indians, this is in stark contrast to their social/attitudinal expectancies.

Path of least resistance: ‘Arbitrage’ offers that least resistance path

in the IT industry, be it cost arbitrage, labour arbitrage, geographical arbitrage etc. But arbitrage means, while you take on market and execution risk, you eschew product risk. Many Indian software entrepreneurs tend to go the arbitrage way rather than choose the high-gestation, high-risk software products path.

Tech isn’t enough: To build great software products, you not only need strong technical and architecture skills, but also strong design, marketing and branding abilities. This isn’t an area of strength for most Indian tech companies.

Under-developed domestic market: Many markets in India may not have the level of depth or maturity required to birth path-breaking next-gen products or technologies. Case in point: The lack of depth forces many SaaS/enterprise startups to start off in India, but they soon hit a wall and are forced to shift overseas to tap into a bigger and more mature market.

*****

To take on the mantle of building world-beating products, the country needs a bit of a mindset change. The success of India in IT services, and of the Indian diaspora in Silicon Valley are pointers that we have the basic ingredients for global success, but some of the ways in which Indians think and act need serious introspection.

India has to learn that ‘quantity cannot be a substitute for quality’. Many of the success factors we track in India are usually in terms of the ‘largest’ and ‘biggest’. But rarely does the country think of in terms of ‘best in quality’, ‘calibre’ or ‘fidelity’. The world of products is driven by perceptions about quality far more than quantity.

The second area where we need a changed thinking is around the need for ‘donning a product mindset (as opposed to a market-oriented mindset)’. Innovative products are about first-principles thinking, where you try to solve a problem as a user-problem first, and not pre-optimise for business or market factors. Unlike projects, building products is a never-ending, long-gestation game and front-loading market or business variables are often a suboptimal strategy.

The third idea that we need to psychologically come to terms with is ‘imitation is often the first step in innovation’. It is fine to copy others, provided you add something on top to improve the system (thus paying it forward), and move up the ladder. Japan and South Korea were initially regarded as copycats that produced low quality copies of Western products, but they graduated up the innovation ladder and are now known for high quality, innovative products.

*****

To generate ideas about possible solutions, we don’t have to look far. The stupendous success of the IndiaStack platform birthed by the Indian state has lessons to offer. The Indian government, with active support and help from the private sector and India’s technology ecosystem, was able to create a unique national digital infrastructure called IndiaStack (comprising Aadhaar, eKYC, UPI, eSign, DigiLocker). This has been widely recognised the world over as a stupendous piece of technology infrastructure innovation. UPI has emerged as the world’s most innovative payments infrastructure, and many governments around the world are scrambling to implement their own UPI equivalent. It is worth asking: What has worked in IndiaStack’s case? How has India managed to pull this off? The answer: IndiaStack is one rare example where the government and the private sector came together in a selfless partnership and backstopped each other. It’s possible a similar approach needs to be adopted in the larger technology ecosystem to solve the product conundrum plaguing the country. What can be done to orchestrate and catalyse the global Indian software products story? To be real, shifts of this nature and magnitude will happen over many years and decades, but here are a few suggestions in this regard:

Making products count: Till recently, India did not recognise software products as distinct from IT services. But in 2019, the Ministry of Electronics & IT rolled out the National Software Products Policy (NPSP), which, for the first-time defined software products and recognised them as a unique entity. The plan is to extend this into a complete categorisation structure for software products, with a directory, listings etc. As they say, if you can’t define (or measure it), you can’t improve it.

Academia-industry interaction: This has to be one of the key long-term drivers of the Indian product renaissance. Silicon Valley came about in the US due to close interactions among industry, government, and academia in the outskirts of San Francisco. We can take a leaf out of that and build multiple localised clusters across India where deep linkages between our universities, engineering colleges, industries and government institutions are enabled.

Catch ‘em young: Silicon Valley technology mega-success stories are replete with accounts of young, brilliant, go-getting college dropouts and social recluses (think Microsoft, Apple). It is imperative to capture the imaginations of our young college graduates, engineers and coders, and give them the intellectual latitude and resources to try out product experiments without the fear of failing.

Funding flow for product companies: It is fair to assume that copious amounts of risk capital will be needed to kickstart and fund Indian software products companies. Again, this can be a combination of the state and private enterprises coming together to make it happen. The Government of India has a Fund of Funds for startups, part of this could be earmarked for pure-play product startups. VC/PE firms that invest in product companies could be accorded special tax benefits or something else (maybe along the lines of the government’s PLI scheme for hardware manufacturing).

Product incubators: India needs specialised product incubators to provide much needed support to its product entrepreneurs. These could come up in the private sector, or in our universities. Some of the successful product entrepreneurs or technology executives from Silicon Valley (of Indian origin) could be officially roped in by the government to act as advisors or honorary members to aid in our product turnaround story.

Playbooks for vertical segments: The success of Indian enterprise/SaaS startups in building global product footprints became possible due to the emergence (and replication) of a playbook that came out of the early winners. The Indian ecosystem needs to develop similar playbooks in other areas like consumer, platforms, infrastructure, or vertical segments like health care, fintech etc.

Amit Ranjan is co-founder SlideShare and architect of DigiLocker Project

First Published: Aug 23, 2021, 12:45

Subscribe Now