Covid impact: The long road to recovery for small businesses

Micro enterprises in the informal sector have been hardest hit by the pandemic. What will it take to get them up and running again?

A leather goods store in Dharavi, Mumbai. Image by Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

A leather goods store in Dharavi, Mumbai. Image by Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Cars honk, the traffic snarls. It is a usual day on Dharavi’s 60 Feet Road in Mumbai. But the shops on either side of the narrow road aren’t bustling with activity as they would pre-Covid. Every few shops dotting the street are shuttered.

“Earlier, at least five people would stop by my shop every day and ask me for directions to the leather market. Today, one buyer in several weeks asks for directions. That’s the state we’re in," says Armaan Ali, 67, a steel trader who has lost Rs 35-40 lakh in unsold inventory since the onset of the pandemic. Dressed in a white kurta-pyjama and a skull cap, he has just returned to his shop after his namaaz prayers. From doing a few lakh worth of business every month, he now struggles to pay his Rs 80,000 rent. “The situation is bad," he says, as his sons hover around listlessly a worker sleeps on the sheets of corrugated steel piled up inside the shop.

Further down the road, Kishor Bagve sits in his garments shop waiting for customers. “Things are improving, but we are nowhere close to pre-Covid levels," says the 45-year-old, who’s been running his business since 2006. He used to rake in around Rs 40,000 in sales every month it’s now down to a fraction of that. “I manage to make Rs 200-400 a day—enough to cover my family’s food expenses for the day." Help from the government hasn’t been forthcoming. “We haven’t received any help. Besides, what will I do taking a loan? How will I repay it?"

The footwear shop adjacent to Bagve’s is shuttered. “He closed down and went back to his village during the first Covid-19 wave," Bagve says about his neighbouring shop owner. “He hasn’t come back since." A cake shop next door is empty of customers. “Nobody really comes anymore," shrugs the attendant. Meanwhile, a roadside tea seller and a vada pav vendor across the street are doing brisk business. A two-wheeler components and maintenance shop also appears busy.

“The pandemic has been an exogenous shock. It’s created far more disruptions in the informal sector than the formal sector," says Pranjul Bhandari, managing director and chief India economist at HSBC bank.

“The pandemic has been an exogenous shock. It’s created far more disruptions in the informal sector than the formal sector," says Pranjul Bhandari, managing director and chief India economist at HSBC bank.

India has an estimated 6.33 crore micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which contribute 29 percent to India’s GDP. Of these, roughly 30 lakh MSMEs are registered under the Udyam registration portal, as of May 2021, according to the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. Registered micro enterprises stood at around 28 lakh (93 percent), followed by small enterprises at 1.78 lakh (6 percent) and mid-sized enterprises at 24,657 (1 percent).

The 6 crore or so unregistered enterprises form the informal economy. The bulk of them—around 99 percent, according to Arun Kumar, professor of economics at the Institute of Social Sciences in Delhi—are micro enterprises, defined as those with a turnover of less than Rs 5 crore.

Adds Bhandari, “Around 20 percent of India’s labour force works in the formal sector, while 80 percent is employed in the informal economy." Out of the 80 percent, half works in agriculture, while the other half—comprising 40 percent of India’s labour force—is typically employed in small firms. In absolute terms, around 300 million people work in the informal sector half of them—150 million—are typically employed in micro and small firms. “They are the ones who have been most disrupted in the pandemic," she says.

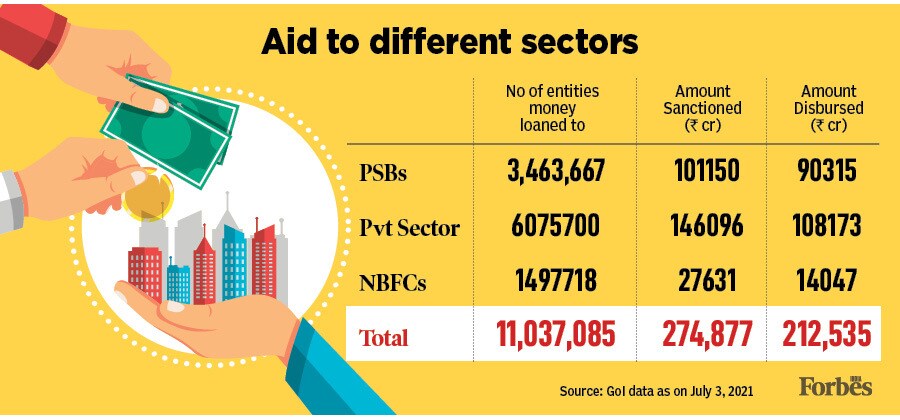

In mid-May 2020, the government announced measures to help MSMEs weather the pandemic. Among them was an unprecedented six-month moratorium on loans and a Rs3 lakh crore package (later extended to Rs 4.5 lakh crore) that extended an emergency line of credit of up to 20 percent of a company’s (MSME and larger units) outstanding credit. The loans, which aimed to provide working capital support for day-to-day operations and overheads like rent and wages, were to be disbursed via banks and non-banking finance companies (NBFCs). The government also provided a partial credit guarantee worth Rs 20,000 crore to banks to encourage them to lend to stressed MSMEs.

As per government data released in July 2021, Rs 2.75 lakh crore (of the Rs 4.5 lakh crore), has been sanctioned to 11 million businesses banks have disbursed Rs 2.13 lakh crore of this.

While the break-up of the kind of businesses that took these loans is unavailable, micro businesses operating in the informal or unorganised sector have largely been left out, says Kumar. There are several reasons for this. For one, such businesses typically employ 1.7 people on an average to be eligible for registration, businesses should employ 10 or more people and use electricity, or employ 20 people or more if they don’t use electricity. “By definition, micro units will not be registered. That’s why the government finds it difficult to reach out to them," explains Kumar.

Second, most micro entrepreneurs are new to credit, which means despite the government’s credit guarantee scheme, banks and NBFCs are wary of lending to them. “Many micro and small entrepreneurs have been running their businesses without loans. In difficult times like this it is challenging for them to become new-to-credit customers. Lenders will be cautious in lending to them as they will be mindful of asset quality. Also, it may be sometime before they get back the money under the government’s credit guarantee scheme, in case a borrower defaults. So, lenders tend to be very conservative in times of crises like this," says Chandra Shekhar Ghosh, managing director and CEO of Bandhan Bank.

A worker cuts leather for a wallet at a leather workshop in the Dharavi, Mumbai. Image by Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

A worker cuts leather for a wallet at a leather workshop in the Dharavi, Mumbai. Image by Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Third, even though economic activity is picking up—as seen by an uptick in GST collections in July and August 2021, where they crossed Rs 1 lakh crore, after dropping in May and June 2021 due to the second pandemic wave, as per GST Council data—the unorganised sector isn’t getting the full benefit, says Kumar. “Demand is shifting from the unorganised to the organised sector. This has been the case since demonetisation," he says. The trend was amplified during the pandemic: E-tailers, for example, benefited as people shopped online, but the corresponding demand from neighbourhood stores fell. “If demand is shifting, why will micro entrepreneurs restart their businesses? It’s a dire situation. Unemployment is very high among them."

In some instances, private players, especially those operating in the micro finance segment, have been able to effectively reach out to this sector. Pinky Yadav, 36, for example, ran a cosmetics store selling lipsticks and nail polishes in a village 2 hours from Patna, before the onset of the pandemic. She started the business to supplement the income of her husband, who is a tea seller. She would bring home Rs 800-1,000 a day, she says. When the first pandemic wave hit and sales plummeted to zero, she took a Rs 30,000 loan from Arohan Financial Services, a Kolkata-based microfinance institution (MFI). She was a customer with them pre-pandemic, and hence was able to apply for and receive fresh credit promptly. “The first two months were very tough," recalls Yadav. “But things have since got better." During those two months she availed of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) six-month moratorium on loans. In the third month she started her repayments, she says.

“The 99 percent collection efficiency that MFIs usually report obviously got impacted during the lockdowns. But we financially counselled our customers and managed collections of 75 percent even in the moratorium period," says Manoj Kumar Nambiar, managing director of Arohan.

Like most, Arohan has been “stringent" with approving new borrowers, says Nambiar. “Even if a business has restarted, has it reached a level of activity where a loan can be serviced? We’re careful about this. It helps that awareness of credit scores is strong among borrowers. People don’t want to be termed NPAs and lose access to formal credit, which can be 10-12x lower in cost compared to local moneylenders."

So how long will it take for things to look up again for the informal sector? HSBC’s Bhandari draws parallels between disruption caused by demonetisation and that caused by the pandemic. “After demonetisation, we saw that large, listed firms got richer and smaller ones got disrupted. But one year down the line, when new currency notes were printed and cash came back into the system, we saw the small firms making a comeback. So, one line of thinking is that as the pandemic slowly eases off, the informal sector will, over time, revive," she says.

On the other hand, she says, “Do we want this big informal sector? Yes, it’s a huge job creator and GDP driver, so we need its presence. But we also need to help them grow into formal sector firms." India is saddled by the problem of “dwarfism", a term used by economists to describe how small firms remain small throughout their lifecycle. Bhandari believes that the pandemic has offered an opportunity to “clean the slate" and build an environment where micro units can grow over time rather than remain dwarfs. This includes finding creative ways to ensure they get access to affordable funds bringing about labour reforms so that they hire and fire easily easing out regulatory hurdles relating to starting, running and exiting a business giving them access to “hard infrastructure" like cheap and consistent power supply and finally, providing “soft infrastructure" assistance such as marketing procurement and technology support.

Already, organisations like the Chamber of Indian Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (CIMSME) have set up dedicated toll-free numbers as well as physical centres (currently only in Delhi) where entrepreneurs can drop in to understand the various government schemes and loans they can avail of. “It’s a stressful time for MSMEs. They need some handholding," says Mukesh Mohan Gupta, president of CIMSME.

With the easing out of Covid-related restrictions, vaccination rates going up and the upcoming festive season, perhaps a recovery might not be that far away.

First Published: Sep 28, 2021, 10:35

Subscribe Now