Lending to the bottom of the pyramid

After successfully navigating the Covid-19 storm, CreditAccess Grameen is well positioned for the next leg of growth

Halfway through my interview with Udaya Kumar Hebbar, the chief executive of CreditAccess Grameen, a line I’d read while preparing for the meeting keeps ringing in my head—‘always be wary of runaway successes in the microfinance space’. I ask him why I shouldn’t be sceptical of their success.Hebbar, who has helmed India’s largest microfinance company for the last decade, takes my question head on, saying that he welcomes the (occasional) bad time in the industry.

“In a normal time, one will never be able to differentiate between a good and bad micro finance company," he says. “When we build a business we need to see how these businesses stand in a bad time. That is the true test."

As he moves on to explain how CreditAccess Grameen is different (more on that later) it’s not hard to see why India’s largest microfinance company not only survived the pandemic but also emerged stronger.

Contrast this with a decade where India’s microfinance industry has been a happy hunting ground for business failures. We’ve had blow-ups as spectacular as SKS Microfinance that was once the poster boy of the industry, or regulatory action in undivided Andhra Pradesh, which overnight made it impossible for the industry to function in a state that in 2010 accounted for half of all microfinance loans in India. Credit culture in states like Assam has also taken a beating.

Survivors—Satin Creditcare or Spandana Sphoorty—have had their books severely dented on account of loan losses during the pandemic. Several small finance banks—Jana Small Finance Bank, Ujjivan Small Finance Bank, Suryoday Small Finance Bank—as well as Bandhan Bank, which has a significant microfinance portfolio, have seen bad loans surge.

Most have been forced to raise capital.

All in all it’s been a tough two years for the industry. During normal times permanent loan write-offs are 1 to 1.25 percent, according to Alok Misra, chief executive of Microfinance Institutions Network (MFIN), an industry association. “This time we could have 6 to 8 percent of the portfolio as write-offs," he says. “For some it could be even more." Still, the massive need for credit at the bottom of the pyramid has resulted in India being the world’s largest market for microfinance. In all, the industry lent to 50.5 million borrowers, with a total loan portfolio of Rs2.32 lakh crore as on December 2021.

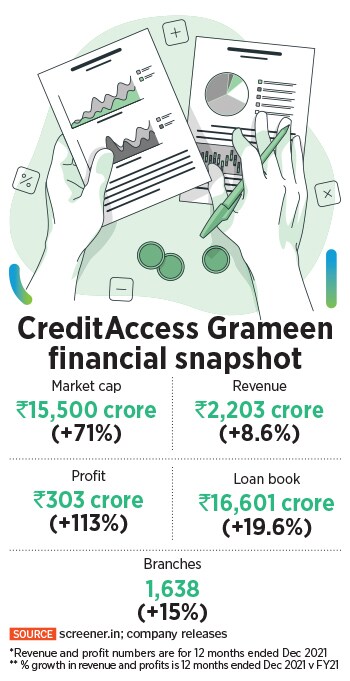

At CreditAccess Grameen, not only has business exceeded pre-Covid levels, it’s also seen a profitability boost on account of lower cost of funds, lesser competition and keeping credit costs in check. Its gross loan portfolio has moved from Rs11,996 crore in March 2020 to Rs16,601 crore in March 2022, an annual growth of 17.6 percent. The Rs15,500-crore market cap company stands out as one of the few survivors in the industry with a balance sheet that gives it the financial capacity to grow. Recent regulatory changes for the industry should make it easier for well-capitalised players like CreditAccess Grameen to grow faster.

Microfinance is a painstaking business and the tendency to take short cuts is often what results in business failures. In the past, as companies tried to grow their books rapidly, they either charged rates that were too high or simply gave customer’s loans far in excess of what they needed. “The borrowers would either spend the money immediately on something they didn’t need or go and put it in a chit fund," says a long-time industry executive who declined to be named citing company policy. As per a March 2022 Reserve Bank of India (RBI) notification, microfinance loans must be restricted to families with an annual income of no more than Rs3 lakh.

Getting it right also takes time. Groups known as joint liability groups are formed, with the concept explained and collateral free loans made to a group for a variety of purposes.

These could be for running a small kirana shop or buying a few cows. In addition, borrowers may also need money for a health emergency or for school expenses or for home improvement. But the principle of joint liability is paramount, and peer pressure for repayment acts as a powerful deterrent against default. CreditAccess Grameen has made sure that groups are properly coached in the joint lending concept, as well as have their antecedents vetted. Each member’s house is paid a visit.

While all microfinance customers need money, they rarely require the same amount. Most companies in this business disburse a standard product to all customers, set up a repayment schedule (usually fortnightly or monthly) and move on. “We follow a limit concept depending on the vintage of the customer so as to not force-fit a customer to borrow beyond their need," says Ganesh Narayanan, deputy chief executive at CreditAccess Grameen. In effect, what the customer has is a credit line that she can tap into when needed. Narayanan also points to the fact that since the company is meticulous about forming the group and the time taken to vet it, a lot of non-serious borrowers get eliminated.

This strategy has worked well for the company and borrowers. Deepanjali, along with her husband Lokesh, from Tumkur in Karnataka were able to set up a kirana shop with a loan of Rs25,000 from CreditAccess Grameen. Over the years, she made use of her credit line to get into dairy farming and later took an individual loan of Rs1 lakh, which was partly invested in a camphor and incense stick packaging business. “Because of this [loan], we also have some savings in the bank," says Lokesh.

Borrowers across the industry usually also have to stick to one cookie-cutter repayment schedule for the group, usually fortnightly or monthly. Structuring different payment options for borrows would require a strong technological base, something most companies are loath to spend on. “We realise that individuals have different repayment cycles and offer them a weekly, fortnightly or monthly payment option," says Hebbar, pointing out that CreditAccess can do this on account of their core banking software. So, both the borrowing and repayment cater to individual requirements, which Misra of MFIN says is unique to the company.

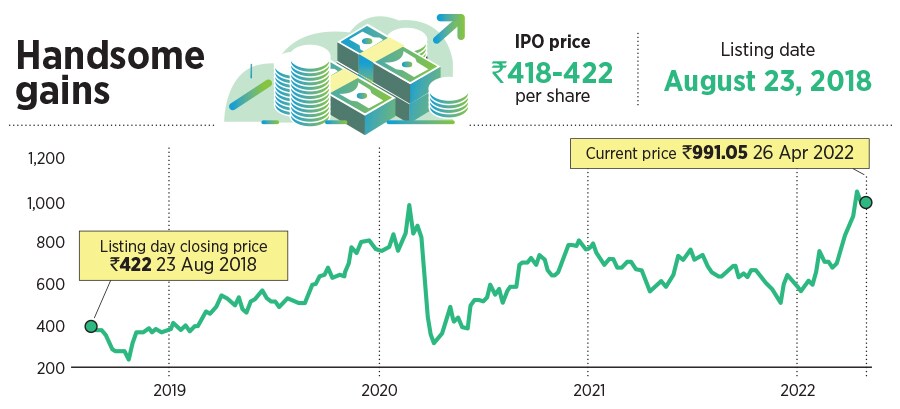

Over the last five years, CreditAccess Grameen, which is over two decades old, has expanded its business model gradually to make sure it stands the test of time. As a result, the market, since its listing in 2018, has progressively given it a higher multiple. The stock has compounded at 18.5 percent a year since August 2018, taking its multiple to four times book value. This is commendable, given that its peers quote at around book value.

“We’ve met the company several times and they are not seeking the maximum possible growth," says Michael King, chief investment officer at Seattle-based Taiyo Pacific Partners LP.

“They are careful about the average loan size and not loading borrowers with excessive debt." In the past, the market has progressively re-rated financial services companies that have adopted a measured growth approach. Two prominent examples include Gruh Finance, an HDFC subsidiary later sold to Bandhan Bank in 2019, which quoted at 11 times book, and AU Small Finance Bank that trades at seven times book.

Part of the confidence comes from the measured manner in which the company has expanded and the huge opportunity size of 60 million households. At present, CreditAccess Grameen serves over 3.7 million customers and is present across 315 districts across the country. Hebbar points out that no one district accounts for more than 2 percent of the portfolio, except seven legacy districts that are slightly above 2 percent.

Expansion is district-wise, with a conscious effort to stay away from areas where the credit culture is poor.

In 2019, CreditAccess Grameen acquired Madura Micro Finance, which overnight brought with it access to the Tamil Nadu market, where it was a weak player. But given the difference in cultures in the two organisations, the integration took time and investors are split on whether a well-run company should grow inorganically due to the cultural mismatch.

Lastly, CreditAccess Grameen has adopted a policy that recognises bad loans at the 60-day mark rather than the regulatory requirement of 90 days. As on March 2022, bad loans beyond 60 days stood at 3.2 percent of the portfolio. This means their bad loan numbers are overstated when compared to the rest of the industry. “The fact that a majority of their loans have weekly payments means their customer connect is stronger," says Misra of MFIN, pointing out that it helps them come up to speed with borrower problems earlier.

Hebbar also hints at write-backs in the coming quarters as collection numbers improve.

A recent change in RBI rules for microfinance companies has expanded the opportunity for companies like CreditAccess Grameen. First, they can lend to borrowers with a household income of less than Rs3 lakh. Second, up to 25 percent of their balance sheet can be used for loans with collaterals, ie non-microfinance loans. This places lenders at a huge advantage as they typically already have a relationship with the borrower or her family to enable them to give them small business loans.

Already CreditAccess Grameen’s cost of funds is 9.05 percent, which compares well with non-banking financial companies offering small business, two-wheeler and home improvement loans. Parent CreditAccess runs microfinance businesses in Indonesia and Philippines and has helped the company access the global market for debt funds. “They have connections outside of India and that has helped us diversify our funding base," says Hebbar. For now, 12 percent of debt is from outside India, which the company plans to take to 30 percent.

On the leverage front, Hebbar expects the company to maintain a gearing of a maximum of four times book value. He explains that while too much leverage increases the return on equity, it makes lenders skittish at loaning money to the company at low interest rates. As a result, he expects return on equity to be in the 18 percent range, with the company raising its next round of capital in FY24.

With the microfinance model proven, the company will have its task cut out growing its book among customers outside of the microfinance bucket. Since they already have an understanding of the customer (she has been a borrower in the past) and they can match rates offered by banks, this promises to be a promising growth area albeit one where net interest margins would be lower. Investors plan to keep a close eye on this vertical. If CreditAccess Grameen proves itself here, growth would be easier to come by. And risk?

Much lower.

First Published: Apr 26, 2022, 12:46

Subscribe Now