The growth headwinds have intensified, and the country finds itself in the midst of growing challenges. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), of course, had not bargained for stubborn inflation and its cascading impact on core macroeconomic objectives as it was confident of a ‘soft landing’ that is ‘well timed’.

But the central bank’s ultra-accommodative monetary policy—of historic low rates for two years to support durable recovery—has not exactly panned out as it may have hoped.

Most central banks worldwide have turned the liquidity tap off—bursting the bubble of inflated asset prices. Since March, the US Federal Reserve has hiked rates by 75 basis points to battle the worst inflation the country has witnessed in 40 years.

![]()

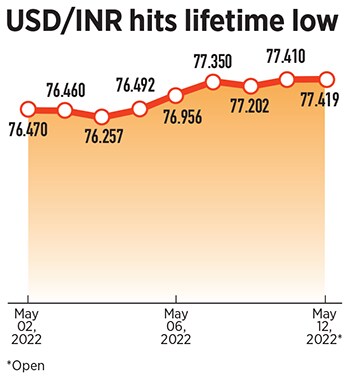

With the US Fed taking aggressive steps to tame inflation, the US dollar surged to a 20-year high, adding sheen to the greenback’s status of a safe haven against currencies of emerging markets during periods of economic upheaval. In fact, foreign institutional investors have been on a selling spree for the last seven months, offloading India investments worth over $17 billion in the current calendar year.

As the greenback strengthens, the rupee hit a record low of 77.63 against the US dollar on May 12, forcing the central bank to step in. The RBI’s calibrated intervention in the currency derivatives markets helped stem a free fall of the rupee. There are multiple factors weighing on the rupee.

“High oil prices, US dollar index at 20 year-high, US 10-year yield above 3 percent, and weak equity markets, the list of negatives for rupee is pretty long," says Anindya Banerjee, vice president, currency and interest rate derivatives at Kotak Securities.

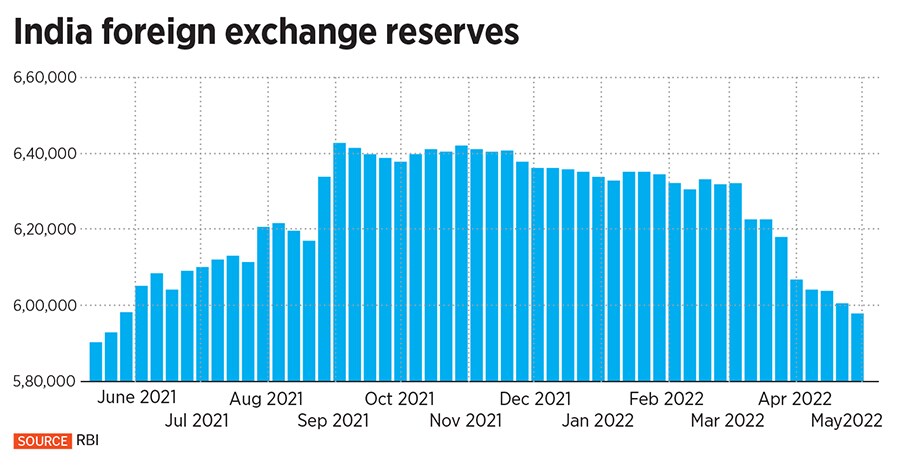

But as the RBI keeps selling dollars to defend the Indian currency amid capital outflows and a strengthening greenback, the country’s forex reserves have steadily declined by over $30 billion, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, from a record high of $640 billion in September.

So long, the RBI has depended on its forex reserves to cushion the fall of the India unit.

Yet, at some point, the central bank will have to limit its intervention to arrest rupee depreciation, since the forex reserves are down by over $36 billion in the current calendar year.

In times of volatility and uncertainty—as during the first and second waves of the coronavirus pandemic—it was the security of strong forex reserves that gave the central bank muscle to weather the storm.

Importantly, higher crude oil prices coupled with a weakening rupee point to deep turmoil in the domestic economy because India imports nearly 85 percent of its total crude oil consumption.

![]()

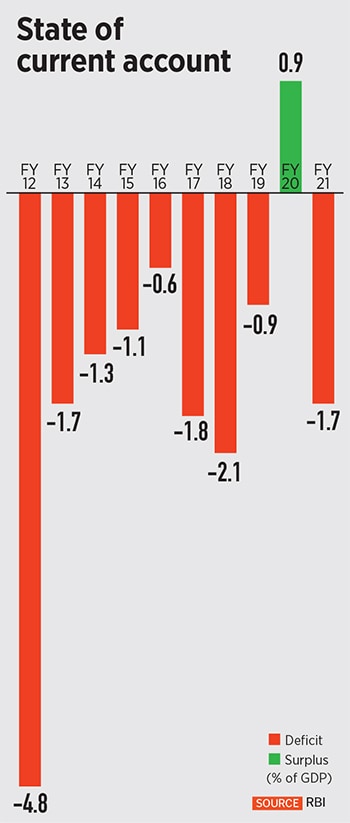

As the global economy struggles to overcome the damaging blows of volatility and supply disruptions due to the Russia-Ukraine war and the rising coronavirus cases in China, the harsh reality of higher interest rates and unfavourable balance of payments due to imported inflation is hard to ignore any longer.

“On the domestic front, focus will be on the CPI number and a higher number could cap gains for the currency," says Gaurang Somaiya, forex and bullion analyst, Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

Evidently, rising crude oil prices—a spillover effect of the intense geopolitical conflict—have strained corporate balance sheets as profit margins are squeezed and companies pass on higher input costs to consumers. Another major impact of surging crude oil prices above $100 per barrel is the widening trade deficit and the deteriorating fiscal health of the economy.

Some economists see the economy heading for a current account deficit of 3.3 percent of GDP, and a balance of payments deficit of around $10 billion in FY23. This is not good news for the Indian currency.

While the rupee is struggling at all-time-lows, retail and wholesale inflation have been elevated for over two years. Headline inflation crossed the central bank’s upper threshold limit of 6 percent in the first three months of calendar year 2022.

In response, the RBI’s rate-setting panel hiked the repo rate by 40 basis points to 4.40 percent in an off-cycle meeting in May. The shock-and-awe move by the RBI made investors edgy—bond yields surged and stock market indices tumbled.

![]()

UBS India’s chief economist Tanvee Gupta Jain expects swift and front-loaded monetary policy actions to reset the benchmark rates as the era of policy normalisation sets in given the RBI"s clear focus on prioritising inflation expectations over growth, neutral real rate being above zero, and signs of uneasiness within the monetary policy committee on imported inflation.

Nomura’s economists say, “The rate hike is a belated acknowledgement of the inflation risks and that policy has been behind the curve. The risk of unanchored inflation expectations and second-round effects have led to an urgent policy pivot."

The brokerage expects a 35 basis points rate hike at the June policy meeting, followed by a 50 basis points hike in August, and further 25 basis points rate hikes at subsequent meetings until April 2023.

“We now expect the repo rate at 5.75 percent by December 2022 versus 5 percent earlier and at 6.25 percent by Q2 2023 versus 6 percent earlier," Nomura’s economists said.

![]()

After tolerating high inflation for many months, the monetary policy committee has dashed into action to contain the second-round effect of supply side shocks. “This means that while supply side factors cannot be contained by monetary policy, the RBI seems to have decided to restrict future inflation by sacrificing demand," says Nikhil Gupta, chief economist, Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

Gupta expects further cuts in GDP growth estimates. “Our non-consensus forecast is already the lowest at just 6.4 percent versus market consensus of ~7.5 percent," he adds.