Will the Centre's national monetisation pipeline plan succeed?

Its new approach to monetising national assets might hold promise, but questions remain about its implementation

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur[br]

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur[br]

Since the Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman announced the National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) plan on August 23 to raise nearly Rs 6 lakh crore, memes have been abuzz on how the nation’s jewels are up for sale. Opinion is still divided on whether India is trying to emulate Australia’s model of monetising assets, or whether some projects will head the way they did in Germany where power utilities were privatised in the 1990s, but were eventually nationalised again. Is this the only way out for the Indian government to fill its coffers for new capital expenditures?Simply put, the government has identified a pipeline of brownfield infrastructure assets across ministries that will be given on long-term lease to private companies. The highest bidder can charge consumers whatever it wants to recover its returns during the lease tenure, and will pay the government upfront capital at the end of the tenure. The asset will then go back to the government. The plan is to monetise assets through an Operate Maintain and Develop (OMD) model. In cases where significant capex may be involved over the transaction life towards building or rehabilitation of the assets, the estimated capex amount will be taken as the monetisation value.

The process is expected to serve as a medium-term roadmap (FY22-25) for the government to raise capital to fund its other projects. The Niti Aayog presentation about the plan does not shy away from admitting that the monetisation plan was “developed in the backdrop of the unprecedented Covid-induced economic and fiscal shocks".

Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman at Feedback Infra, says, “It is principally a big and bold move and financially it is the logical thing to do to generate cash to build new infrastructure."

He cites the examples of how other governments have also tried to monetise assets and that the current one isn’t alone. For instance, the privatisation of the distribution arm of the Delhi Vidyut Board in 2002, when the Delhi government sold a majority stake in three distribution utilities. Although the total operational and commercial losses of the electricity board were around 50 percent, the government managed to offload the assets to BSES Rajdhani Power Ltd and Tata Power.

However, all such attempts have not been successful. In 1999, the Odisha government was the first to privatise its discoms in India by unbundling it into four separate companies: NESCO, WESCO, SOUTHCO and CESCO. US-based AES Corporation’s India arm won CESCO, while the other three companies were won by BSES (now Reliance Infrastructure). In 2001, AES walked away due to commercial unviability of the project—it didn’t sell its stake in it, thus beginning a legal battle over decades—and left CESCO under the supervision of Odisha Electricity Regulatory Commission (OERC). In 2015, OERC revoked all three distribution licenses awarded to Reliance Infrastructure, citing its failure to be commercially sustainable. In June 2020, Tata Power won a 25-year lease to run CESCO (renamed CESU) in December it took over two more discoms and committed further investments.

In September 2020, the Odisha government also reversed its privatisation policy and bought the 49 percent stake held by AES in Odisha Power Generation Project (OPGC). The move came after Adani Group announced in June 2020 that it had signed a share sale agreement to acquire AES’s stake in the project.

Legal tangles and policy changes are concerns that investors have while deploying capital in India. The lack of a central dispute mechanism is also a reason why sovereign and patient capital have shied away from participating in these deals.

“Monetisation of assets has been taking place in India in bits and pieces over the last two years," says Manish Aggarwal, partner and head of infrastructure at KPMG in India. “The challenge has been that global institutional investors like sovereign and pension funds have been waiting for a clear roadmap on how things will play out over the course of the next few years and the kind of assets they will be able to bolt on to their investments. Now there is a roadmap for the next four years and investors are keen to participate."

In 2019, the National Highways Authority of India identified 6,000 km to include under the Toll Operate Transfer (TOT) model. In 2019, Sydney-headquartered Macquarie Group won the rights to manage 648 km for Rs 9,681.5 crore for a long concession period of 30 years.

“However, the key would be to structure these transactions with a balanced risk-reward framework so that the entire risks are not passed onto the private sector," says Aggarwal. “This also necessitates the need for a professionally staffed, independent, commercial disputes resolution body, and a well-functioning and mature regulator that can be approached in case of commercial and regulatory disputes." In November 2015, a report by the Kelkar Committee, which was set up to evaluate public-private partnership (PPP) models, had clearly suggested that India needs a PPP adjudication tribunal for commercial dispute resolutions.

Dinesh Arora, partner and leader for deals at PwC, believes the NMP marks a shift in the way the Indian government looks at national assets. “In the past, PPP models have had their own set of challenges, and hopefully when details [of the NMP] come out they would address some of these challenges," he says.

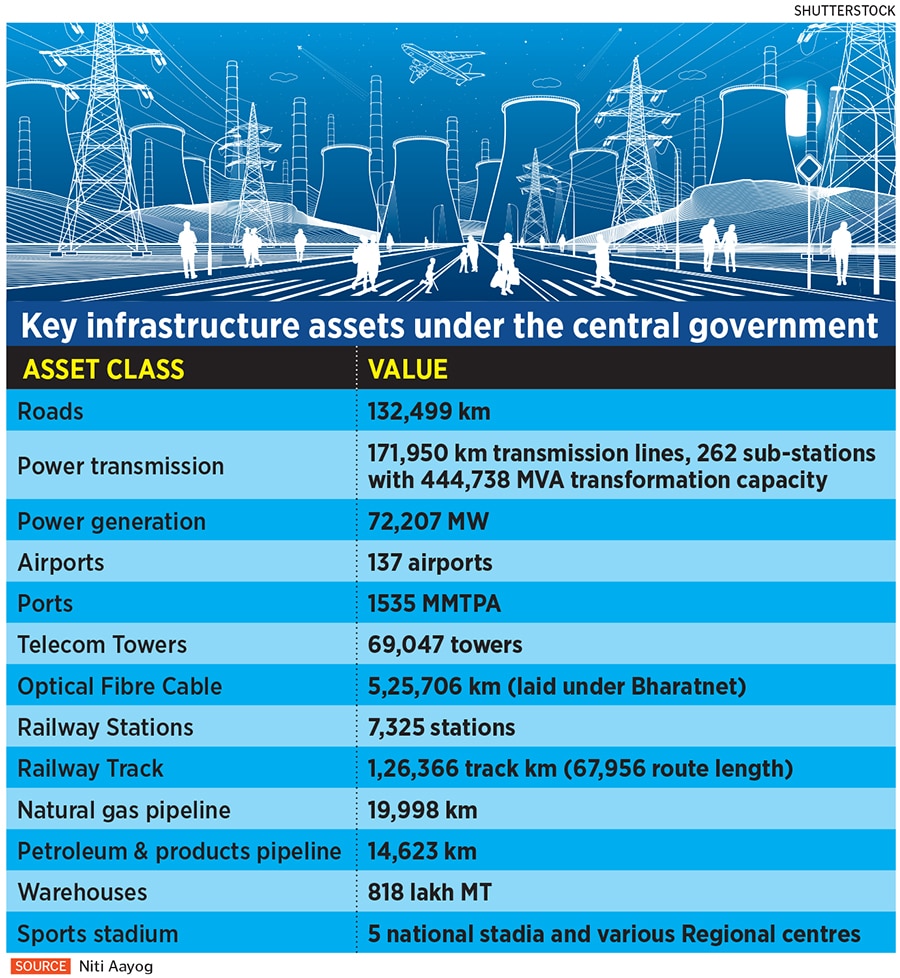

This time the central government has stepped up and identified the specific approach it will adopt to ascertain the value of projects. For example, sectors like ports, airports, railways, sports stadium, warehousing, mining, Bhartnet fibre assets under telecom, and urban housing redevelopment will follow the capex approach. Under this, a sizeable capital expenditure will go towards the expansion or improving the quality of infrastructure delivery during the lifecycle of the lease. Hence, the extent of private investments estimated towards capex has been considered as indicative of the monetisation value. Whereas roads, power transmission and telecom tower assets will be leased through the market approach, power generation and infrastructure under DFCCIL will be assessed through book value, and natural gas pipelines and product pipeline assets will be evaluated under the enterprise value approach.

One of the reasons why the Centre needs to push through this monetisation programme of brownfield assets is the lack of private participation in greenfield infrastructure investments. Private equity funds and infrastructure firms have burnt their fingers in the post-2008 era, when they had bid aggressively for contracts and were unable to get required returns on investments.

As India’s GDP grew rapidly between 2003 and 2008, financiers and companies projected aggressive returns. Most infra funds and companies have folded up since then, or have struggled to survive, especially power and road companies. The new wave of investments have been made to acquire ready toll road assets or green power projects. Thus the government is now forced to build new infrastructure projects on its own.

To build anything the government needs capital, and its disinvestment programme has not been very successful over the last three years. India’s National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) envisages an infrastructure investment of Rs 111 lakh crore over a five-year period (FY20-25). As estimated by the report of the task force for NIP, traditional sources of capital are expected to finance 83 to 85 percent of the capital expenditure, while 15 to 17 percent of the aggregate outlay is expected to be met through innovative mechanisms, such as Asset Recycling and Monetisation and new long-term initiatives such as Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). As an incentive for asset monetisation, additional allocation equivalent to 33 percent of the value of the assets realised is envisaged to be deposited in state consolidated funds or in accounts of public sector enterprises owning the assets.

The one shot in the arm that the Indian government desperately needs is the kick-starting of the monetisation process to raise capital to bridge its financial gaps. According to the Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM), since this April, disinvestments have yielded Rs 8,368.61 crore, which were all raised through the offers for sale (OFS) route. For FY21, the government raised only Rs 32,845.18 against an ambitious target of Rs 2.1 lakh crore. While the Covid-19 pandemic took the sheen off the sale process, things had not been rosy in FY20 either, when disinvestments stood at

Rs 50,298.64 crore.

“The government needs capital to finance development activities and there are two ways to do it: Either raise debt or wait for socio-economic development in the country. But this model of leasing allows the government to raise money to finance development activities," says Devendra Pant, chief economist at India Ratings & Research, the Indian arm of Fitch Ratings.

India’s debt is expected to be around 61.7 percent on provisional basis for FY22. Thus, mounting more debt isn’t on the cards for the government. But Pant cautions that the crucial part here is that in some cases in Australia and other parts of the world, winning bidders have not maintained the assets properly, and have not expended capital for regular operational expenses to the extent that the asset has decayed faster than its economic life.

One question that has found centre stage during these discussions is how much private players will charge consumers. Will these infrastructure assets become costlier for common people to access or how frequently will the charges be increased? There have been instances in other countries where, due to increase in tariff charges, the government was forced to renationalise the assets.

But Pant says one thing is clear: The government needs capital. He adds that if there are domestic players, then they will bid on the basis of domestic interest rates, whereas global investors will find it cheaper to raise capital and deploy in India. For instance, 10-year G-sec notes are at 6.25 to 6.30 percent. Thus, domestic players with high ratings would be able to raise capital in the 7 percent range, whereas global funds will be able to raise capital at around 6 percent. This 100 basis points can end up making a huge difference.

“International players have an advantage of more than 100 basis. It can make or break a project because then you need lower internal rate of returns [IRR]. If they need lesser money, they will bid better than domestic players," adds Pant.

Another important aspect is between FY12-20 the savings rate in India came down, and household savings have come down sharply as well the gap between the government’s requirement and household savings is narrowing. While for the NMP, the money should not be a problem because India is at the lowest curve when it comes to interest rates, but as and when the economy revives and liquidity goes down, it will put pressures on domestic interest rates. Thus, getting these deals done quickly is the only way out for the government, as corporates too want to lock cheaper interest costs for the projects.

The final question that is consistently being raised about the monetisation plan is, will a select few corporates who are considered to be closer to the government manage to bag all the prized assets. As Chatterjee, of Feedback Infra, says, “there is a genuine apprehension, and thus the process of handling this should be transparent. Once you have embarked on a project like this, you need transparency and a central point of coordination."

Bankers and lawyers, on conditions of anonymity, have repeatedly mentioned how nearly 113 firms attended the pre-bid for PPP projects under the Indian Railways but only three ended up bidding as institutional investors, and sovereign funds found they were not getting a level playing field. Hopefully with this large scale monetisation plan the time has come for India to truly run deals independently.

First Published: Aug 31, 2021, 12:07

Subscribe Now