In another case involving Anil Ambani-led enterprise communications services provider Reliance Communications, a resolution is still to be arrived at since May 2018, when the case filed by telecom equipment manufacturer Ericsson India was admitted at the NCLT. There have been concerns that the regulator had raised earlier on whether an asset reconstruction company can buy RCom’s spectrum and other assets as part of the resolution.

Talks have emerged that the Department of Telecommunications may not renew RCom’s telecom license later this month, due to unpaid statutory dues. This will hurt the complete insolvency resolution process further and only mean erosion in the value of assets, forcing banks to take more haircuts.

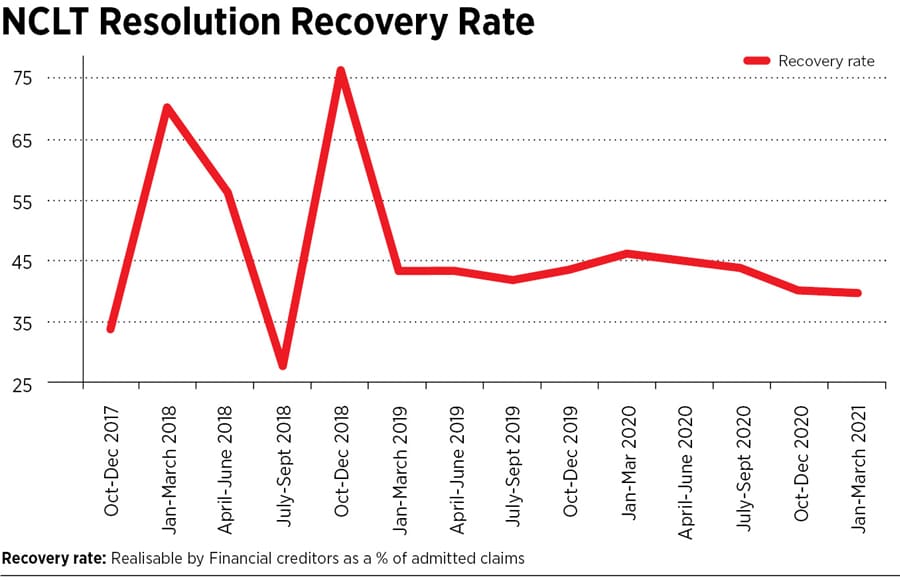

The NCLT, which was seen as one of the mega reforms to tackle bad loan recovery, has completed just over five years of operation. Its success can be measured with two different matrixes: Recovery rate (what banks and other financial institutions recover as a percentage of the amounts claimed) and average number of days taken for the resolution process to be completed.

Recovery Rates Falling Litigations Lengthening

Considering this, the performance of the NCLT can be divided into two parts: The early period that saw the resolution of large cases, loosely called the ‘Dirty Dozen’ (see table), including Essar Steel, Bhushan Steel, Jaypee Infratech, Electrosteels Steel and Monnet Ispat and then the later period from 2019-20 onwards, where recovery rates for creditors have only stagnated or continued to fall. This also means that banks have suffered sharp haircuts—a reduction or depreciation in the value of the asset and the outstanding loan amount due—during the resolution. This only raises concerns over the efficiency of the NCLT process.

![]()

Banks and financial institutions have been able to recover only 39.26 percent of admitted claims, according to the latest January-March 2021 data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. This recovery rate is the lowest in three years, since the July to September 2018 rate of 26.28 percent (see chart ‘NCLT Resolution Recovery Rate).

![]()

The NCLT is however, still, the most effective mechanism, compared to other channels to recover bad loans. In 2019-20, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data showed the IBC to have a recovery rate of 45.5 percent, compared to 26.7 under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 (Sarfaesi Act), 6.2 percent for Lok Adalats and just 4.1 percent for debt recovery tribunals.

Obviously, the spread of the pandemic has hurt tribunal proceedings since March last year, with NCLT proceedings coming to a crawl. A deeper look at the functioning of the NCLT, however, reveals a whole range of problems plaguing the system.

These include delays in admission of cases where it often takes 6-12 months to admit a case, tribunal delays in releasing orders, filing of multiple applications by creditors, lack of consensus within the committee of creditors, inadequate bench strength of NCLT judges to hear cases, which results in the pressure of multiple jurisdictions, and delay in infusion of funds by investors as envisaged by the plan.

“There has been a significant amount of frustration that has crept into the system currently, as delays cause creditors, investors and other stakeholders to wonder if this is a worthwhile mechanism to quickly resolve stressed companies. As at December 2020, a total of 21,259 cases were pending before NCLT of which 9,549 pertained to IBC," says Nikhil Shah, managing director of Alvarez & Marsal (A&M), who leads the firm’s restructuring, turnaround and corporate finance practice.

Some of the data relating to resolutions at the NCLT is not impressive. Until FY21, 4,376 cases have admitted for insolvency resolution in NCLT, of which about 2,653 cases (60 percent) have been closed. Of this 60 percent, for 1,277 cases, an order of liquidation has been passed but the final report of liquidation has been received only for 19 percent of these cases.

Of the 348 cases resolved in NCLT as of March 2021, the average time for resolution, including litigation time, is 459 days. This is way beyond the revised time limit of 330 days prescribed by the government in July 2019. Prior to this, the expected time frame for a resolution was pegged at 270 days.

“At the current pace of disposal of cases and the backlog, it is likely to be cleared in 4 to 5 years," Shah, says, who has advised the Bankruptcy Law Reform Committee and the Insolvency Law Committee in strengthening bankruptcy laws in India.

“Resolutions are not becoming efficient because while there may be settled precedents, the discipline of the law is not being adhered to in full. Same or similar issues consume the time of tribunals, “says Suhail Nathani, managing partner at law firm ELP.

The pandemic has created a peculiar situation for both ailing companies and corporates seeking recovery of their loans. Corporates have taken advantage of government aid through emergency credit lines from the RBI and moratoriums on loans to be paid. But these are temporary life support systems, and business and economic uncertainty continue to prevail.

“In the pandemic, creditors have been providing stressed companies more time to either climb out of the crisis or allowing them to access government-backed credit lines, which have managed to keep the them standard," Shah says.

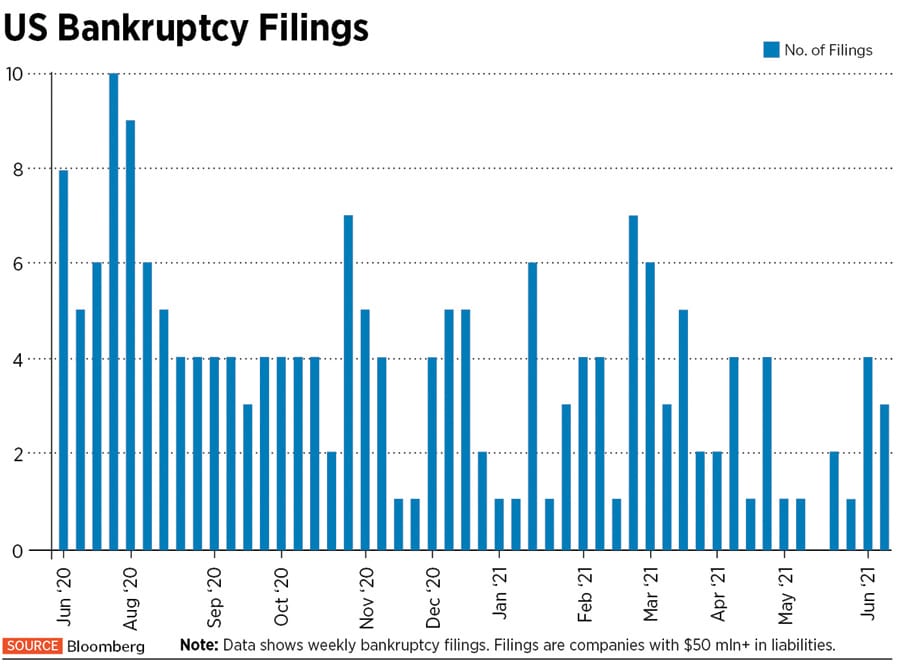

There is a similar trend in the United States, where the number of large corporate bankruptcy filings have slowed dramatically in the April to June quarter this year, based on Bloomberg data (see table ‘US Bankruptcy Filings’).

![]()

Creditors do not want to be seen as blood-sucking villains at a time when most businesses have collapsed due to the pandemic. Even if they are to enforce resolution proceedings against a company, there is not much clarity on what creditors could recover.

NCLT’s Problems Alternatives

Legal debates, infrastructure-related issues and pandemic-induced suspensions have impacted resolutions at the NCLT. There have been long delays in the admission of cases, which A&M estimates to be 6 to 12 months. The insolvency petition for Reliance Naval and Engineering Ltd. (RNEL) was admitted in January 2020 after 16 months, during which time the Supreme Court had quashed RBI’s February 2018 revised resolution framework, even though the original insolvency application was made independent of the RBI circular.

At times, creditors have been unable to resolve their disputes and work for a collective resolution. Since the IBC does not distinguish different security rights for the purpose of the CoC (Committee of Creditors), unsecured creditors or creditors that have subservient charge tend to challenge the claim and distribution under the resolution plan at each stage, the A&M report says.

In many cases, the successful resolution applicant has delayed the infusion of the funds either for business purpose or for upfront payment to creditors as envisaged in the plan, either due to ongoing litigation or disputes emerging during the implementation stage.

This causes unnecessary damage to the business and may negatively influence the outcome of the plan. This is what happened when Liberty House Group—controlled by billionaire Sanjeev Gupta—and Deccan Value Investors filed for withdrawing the plan for Amtek Auto. Liberty House also gave up on bidding for ABG Shipyard.

One of the other problems is the lack of adequate bench strength of NCLT judges. “This needs to be done on a war footing. The bench strength was budgeted for a total of 63, now there are only around 30 judges, whose schedules are extremely stretched. They are often handling as many as three or four different NCLT jurisdictions like Mumbai, Pune, Delhi," says A&M’s Shah.

The slowdown in the resolutions and liquidations at the NCLT has forced parties to look for solutions outside of the NCLT. In November last year, the lenders to equipment maker CG Power and Industrial Solutions agreed to a one-time loan restructuring, which will allow Murugappa Group’s Tube Investments to acquire the company. The board of CG Power was reconstituted and under the one-time settlement (OTS) scheme, the consortium of banks agreed to a 53 percent haircut and the entire debt of Rs 2,161 crore was settled at Rs 1,000 crore.

In April, one of the first and largest one-time (Covid-19 related) restructuring was finalised, under the resolution framework of the RBI, whereby lenders agreed to Rs 10,900 crore debt restructuring proposal from the Shapoorji Pallonji Group. An RBI constituted KV Kamath committee approved the plan.

Pain for Banks: Videocon, Jet Airways

Plaguing the NCLT process is the fact that bankers know if a resolution is difficult, liquidation is not an option. “When a case goes into liquidation, the recovery suffers massively. If a matter is not resolved and it goes for liquidation, the assets will be sold piece-by-piece," says Vivek Kaul, an independent economic commentator. This is the reason why banks have in the past chosen to accept resolutions even if they get a raw deal along the way.

In debt-ridden Videocon Industries’ case, lenders have agreed to take a haircut of nearly 96 percent, the NCLT has observed while approving the Vedanta group’s Twin Star Technologies bid for Videocon. The claims admitted were for Rs 64,838.63 crore and the resolution plan was approved for just Rs 2,962.02 crore…. just 4.15 percent of the total outstanding claim amount.

The same has happened in the case of bankrupt and grounded Jet Airways, where the resolution—in favour of new buyer UK-headquartered Kalrock Capital and UAE-based Murari Lal Jalan—has taken over two years. The Kalrock-Jalan combine has agreed to pay financial creditors just Rs 1,183 crore over the next five years, against the admitted claims of over Rs 15,000 crore.

Even as plans are on for the airline to restart operations with a small fleet of 25 aircraft, there are some real challenges. The airport landing slots will not be restored back to the airline. Meanwhile, its rivals SpiceJet, IndiGo and Vistara have all built operational muscle, plying on more routes and with more fleet.

Even as the concerns over the NCLT’s success persist, the coming of the Bad Bank will “be a good plug-in" into the entire system to help in recovery of bad loans, says Kaul, the author of Bad Money: Inside the NPA Mess and How It Threatens the Indian Banking System.

Essar, Bhushan Steel: New parents and Healthy Again

Not everything spelt bad news for the NCLT. There have been some real success stories, through the resolution of Essar Steel and Bhushan Steel. Steel companies, then, were the low-hanging fruit and the asset quality of the companies was good. “Steel was in an upcycle and everyone wanted steel assets," Kaul says.

Essar Steel was acquired by global steel giants ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel in December 2019 and renamed ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel India (AM/NS India), through the joint venture. AM/NS India, an integrated flat carbon steel manufacturer, reported a record $403 million Ebitda for the March-ended quarter, a 188 percent jump from levels a year earlier. The company also reported strong production of 7.3 million tonnes.

Tata BSL—formerly Bhushan Steel—acquired by Tata Steel in 2018, reported a multiple times jump in its consolidated net profit of Rs 1,913.73 crore for the March-ended quarter, compared to just a 5.9 crore profit a year earlier. Total income for the company jumped 71 percent to Rs 7,348 crore in FY21. The stock has surged 328 percent in a year to Rs 91.2 at the BSE, led by the strong global recovery in commodity prices.

India will embark on a fresh chapter of reform when the Bad Bank commences. The fact that India’s pace of growth contracted 7.3 percent in FY21 indicates that business activity and growth was not healthy. Banks may have then merely kicked the bad loan can down the road, without necessarily recognising bad loans immediately. In that scenario, NPA levels are likely to remain high in FY22, with the RBI forecasting Gross NPA level to rise to 9.48 percent by March 2022 from 7.48 percent a year earlier. In a severe stress scenario, the figure could rise to 11.22 percent.

India will need to exercise the option of the NCLT and the Bad Bank to resolve its bad loans recovery in the years ahead. Experts say the NCLT is at an inflection point, with a need to improve the outcome and competitiveness for insolvency resolution. So in coming years fewer cases may go to NCLT due to current problems, but that may actually emerge as a blessing.

The NCLT has ensured that a promoter cannot have a free ride or continue to master control over their company fraudulently. For too long, India has seen a corporate history where companies have failed but promoters have not. That gap will only narrow with the NCLT process.

"‹